Over 30 years of anarchist writing from Ireland listed under hundreds of topics

Gender

Abortion: Anti-Choice Law Challenged in North of Ireland

A Judicial Review into the North's abortion law has begun today and is expected to last three days. The final decision of the case taken by the Human Rights Commission (HRC) is not expected until the Autumn. Women's right to bodily autonomy must be vindicated without delay.

A Judicial Review into the North's abortion law has begun today and is expected to last three days. The final decision of the case taken by the Human Rights Commission (HRC) is not expected until the Autumn. Women's right to bodily autonomy must be vindicated without delay.

Currently in the North you can have an abortion if the pregnancy endangers the life of the mother, including risk of suicide, and if you are under 9 weeks gestation.

Abortion: Legal Challenge to Exclusion of N. Ireland Women from NHS

The Court of Appeal has reserved judgement on a legal challenge to the exclusion of women from N. Ireland from NHS abortion services.

The Court of Appeal has reserved judgement on a legal challenge to the exclusion of women from N. Ireland from NHS abortion services.

Last May Mr Justice King ruled in the High Court that the residence-based exclusion was lawful, despite the fact that people living in the North pay the same amount of taxes as everyone else in the UK and should therefore be entitled to the same services. The case was brought forward by a woman known as A in order to protect her identity and her mother.

Three years ago, A, like many other women from the island of Ireland, had to raise the nearly £900 to avail of an abortion in England.

Marriage as a Bourgeois, Patriarchal Tool Which Has Been Used to Trap Women

Fionnghuala is calling for a Yes vote but she also argues from an anarchist feminist perspective against the institution of marriage. It is a bourgeois, patriarchal tool which has been used to trap women, our sexualities, as well as to force reproduction and to force a woman to enter into reproductive labour.

Marriage Equality: Assimilation is Boring, I Want Liberation

This year it feels as if there has been a revamping of homophobia in the north which has had, unsurprisingly, significant support from the church and those in political and therefore institutional power.

This year it feels as if there has been a revamping of homophobia in the north which has had, unsurprisingly, significant support from the church and those in political and therefore institutional power.

We have witnessed the DUP quash the third attempt to legalise queer marriage, bigoted ‘Christian’ bakers refusing to follow through with a service they advertised because it went against their “deeply held beliefs” (not to mention all the other services they provide that do go against their beliefs). This was followed by the the DUP attempting to bring in a 'Conscience Clause' to legalize and institutionalize homophobia; to make it legal to refuse service to someone because of their sexuality. The above examples are only a few of the homophobic incidents that have taken place recently.

The resistance and the fightback from these incidents must be queer-led and supported by our straight allies. Moreover, it should be noted that incidents like the above push us into a defensive stance; as opposed to an offensive one.

Shame on Labour for Opposing Fatal Foetal Abnormality Bill

Tonight members of the Labour Party voted against a bill which would allow abortion in situations where the foetus has no prospect of survival.

Tonight members of the Labour Party voted against a bill which would allow abortion in situations where the foetus has no prospect of survival.

The second time they did this was after Savita Halappanavar died in October 2012. Within months of this they again voted against abortion.

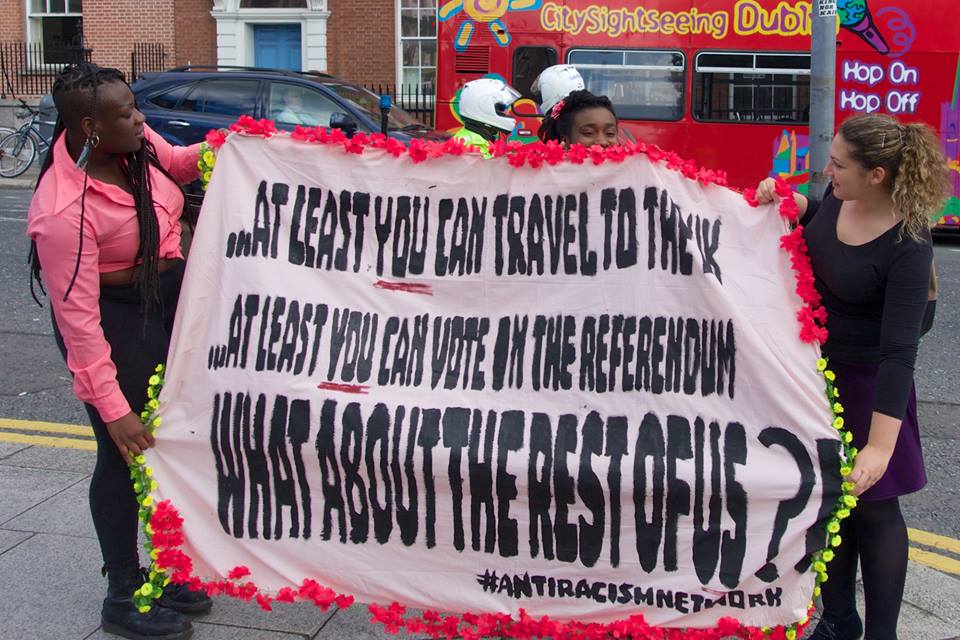

Abortion: Just Travel to England?

The Irish Family Planning Association (IFPA) revealed yesterday that over the last 12 months alone they have seen 26 asylum seekers or women with travel restrictions who indicated they wanted an abortion but were unable to travel abroad. At least 5 of those women were forced to continue the pregnancy to term.

The Irish Family Planning Association (IFPA) revealed yesterday that over the last 12 months alone they have seen 26 asylum seekers or women with travel restrictions who indicated they wanted an abortion but were unable to travel abroad. At least 5 of those women were forced to continue the pregnancy to term.

For too long people have allowed the state to continue to deny bodily autonomy because the trip to Britain for an abortion was a difficult and expensive option but one still available to many. What was ignored was that those unable to access such abortions were the most marginalised, those with little or no voice. As the IFPA revealed as well as Asylum Seekers this includes "women in poverty or on low income, young women, women with disabilities, women in State care, women experiencing domestic violence and women with travel restrictions”.

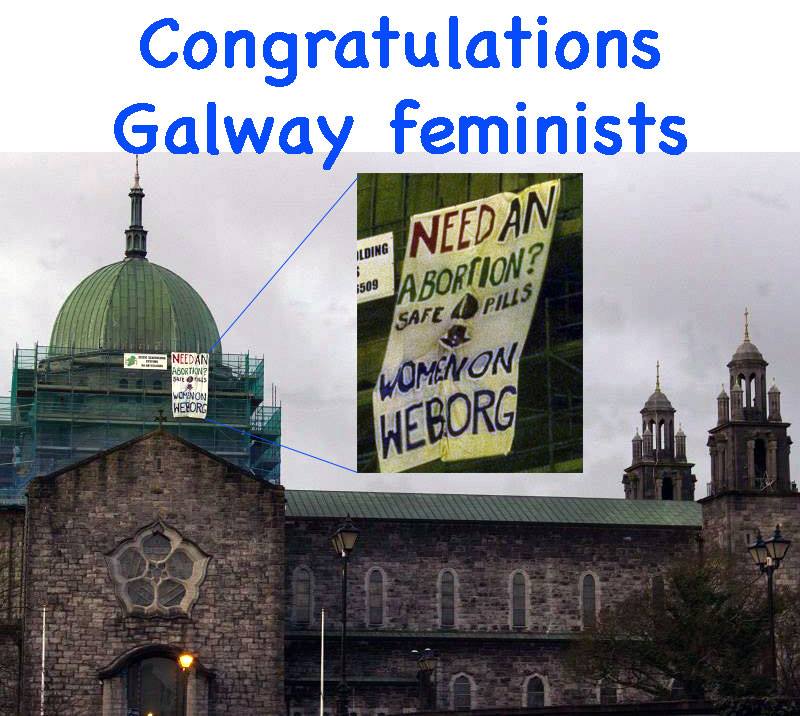

Galway Feminists Banner Drop off Cathedral

A few days ago the catholic bishops yet again dared to lecture people in Ireland with their statement against marriage equality. This morning Díobháil, a new Galway feminist group, has used Galway cathedral to speak out for and help the women trapped in unwanted pregnancies because of the bishops' role in another referendum, the 1983 anti choice referendum.

A few days ago the catholic bishops yet again dared to lecture people in Ireland with their statement against marriage equality. This morning Díobháil, a new Galway feminist group, has used Galway cathedral to speak out for and help the women trapped in unwanted pregnancies because of the bishops' role in another referendum, the 1983 anti choice referendum.

In the years since 1983 it emerged that the same bishops had conspired to hide priests who had raped children, not just on one or two but on many occasions. Despite that this same group of supposedly celibate men still continue to bother us with lectures opposing sexual freedom, bodily autonomy and even same sex relationships. The same bishops still have de facto control over most of our schools and many of our hospitals and community centres.

Review: Silvio Federici's Caliban and the Witch – Women, the body and ‘Primitive Accumulation’

This piece of work is undertaken from the viewpoint of the seemingly invisible struggles of women against authoritarian rule, the historical erasing of women as being part of the wider social struggles for liberation against oppression, and indeed, providing a different type of revolutionary struggle in their own right instead of examining the effects of social reproduction and labour of women.

The IRA and Rape Culture - “When The Violence Causes Silence We Must Be Mistaken”

Growing up in West Belfast, as Maíria Cahill did, you are immediately introduced and submerged into a culture of republicanism and of the armed struggle. Murals, flags and gardens of remembrance make it impossible to escape. What is lurking in the shadows of these symbols and the shadows of local heroes is the clandestine sexual abuse that went on during those turbulent years – clandestine to the public but an open secret within the republican family.

Growing up in West Belfast, as Maíria Cahill did, you are immediately introduced and submerged into a culture of republicanism and of the armed struggle. Murals, flags and gardens of remembrance make it impossible to escape. What is lurking in the shadows of these symbols and the shadows of local heroes is the clandestine sexual abuse that went on during those turbulent years – clandestine to the public but an open secret within the republican family.

Living in a community where Sinn Féin have an absolute political monopoly, it was incredibly brave of Maíria to waive her right to anonymity and challenge the conventional wisdom that surrounded her case – the conventional wisdom that the IRA was responsible for. What we have seen as result, is an attempt by Sinn Féin, as they quite often do, to make Maíria’s rape something it is not. They are trying to write this off as an attack on Gerry Adams and are actively adding to rape culture by implying that Maíria has made it all up for these ends.

Insurrections at the intersections: feminism, intersectionality and anarchism

A critique of liberal conceptions of 'intersectionality' and an outline of an anarchist, class struggle approach.

We need to understand the body not as bound to the private or to the self—the western idea of the autonomous individual—but as being linked integrally to material expressions of community and public space. In this sense there is no neat divide between the corporeal and the social; there is instead what has been called a “social flesh.” - Wendy Harcourt and Arturo Escobar1