Belfast anarchism in the Early Twentieth Century

It was not until the early twentieth century that an anarchist group was established in Belfast. Although we have little information on anarchists elsewhere on the island, it seems entirely possible that this was the first specifically anarchist group north or south. It emerged in a time of rising militancy, though not working class militancy, and when communal relations were especially strained, and proceeded from the propagandist labours of two remarkable Scottish anarchists. One of these individuals, John or ‘wee’ McAra, as he was also known, is a subject in this chapter. The other person focused upon here is perhaps Ireland’s most well-known anarchist, the quixotic Captain Jack White, founder of the worker’s militia, the Irish Citizen Army, who made the philosophical journey from Empire loyalist to Republican nationalist to communist and finally to anarchism. Both of these anarchists highlight the irony of politics on this island and the impact of sectarianism, industrialisation and the marginalisation of the left.

The first two decades of the twentieth century were a tumultuous time for the city of Belfast. With a total of 387,000 people by 1911, it was the largest city in Ireland, and had 21% of the island’s industrial working class. Despite this, trade unionism was strong only among sections of the skilled working class and industrial militancy all but null and void until the great 1907 dock strike. (1) However, the re-ignition of communal tensions around the thorny topic of home rule over 1911 and into 1912, led to the establishment of paramilitary ‘orange and green’ sections. These bourgeois nationalisms found common cause in the chance of martyrdom for their respective causes (aped by republicans in 1916 with their ‘blood sacrifice’), during the ‘Great War’ of 1914-18, and sectarianism was ratcheted up by the post-war ambitions of Irish nationalism. Socialist politics only emerged in any substantive way thereafter and were monopolised by the nascent Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP), formed in 1924 and committed to a gradualist if amorphist programme of social reform.

John McAra (c.1870-1925)

John McAra was a cooper from the village of Mid-Calder, close to Edinburgh, the city with which he was most associated and to which he moved sometime late in the 1880s.(2) The details of his connection with Belfast are scant and although well-attested, rather lacking in detail. We owe much of what we do know about him to Mat Kavanagh, whose memoir of ‘wee McAra’ was published in Freedom, the London anarchist newspaper, in 1934. According to Kavanagh, McAra was ‘one of the quaintest and pluckiest’ anarchists in the movement, and a great individual activist and propagandist. A downside of his activity, however, was his tendency never to form or belong to a group, so that after a period of intense work in a particular region or city nothing was left to continue the fight after his departure. This bears resemblance to a number of other independent or non-aligned anarchists who saw their role simply as a propagandist and/or non-prescriptive one.

Although Kavanagh fails to mention it, McAra’s activity in Belfast did, in fact, leave a group in its wake, though this may have had its origins out of those who supported him while a prisoner in Crumlin Road gaol.(3) As with many other areas discussed in this work, much more research needs to be done before we know exactly when the first Belfast anarchist group was launched and who was involved with it, as well as the wider question of its efforts and impact.

There is a strong possibility that John McAra’s initial involvement with anarchism came through the Socialist League, mentioned previously, which served as the nursery of a good number of anarchists. The Edinburgh branch in particular was noted for its anarchist sympathies due to the impact and energy of the veteran Austrian anarchist, Andreas Scheu (1844-1927), a close confidant of William Morris, who had lived in ‘Auld Reekie’ since 1885. Whatever the case, McAra was an active outdoor speaker on Edinburgh’s Mound, and fought and won a campaign in the courts to have public speaking remain free and unmolested by the authorities, despite being ridiculed, castigated and ignored by contemporary socialist groupings in Edinburgh. McAra also helped revive Glasgow anarchism around 1909 which had fallen into disrepair after the heady days of the 1890s.(4)

We don’t yet know the exact date of McAra’s visit to Belfast but it may have been part of his travelling speaker days between 1900 and 1910, where he visited a number of places to propagandise for the cause of anarchism. The event for which he was arrested does allow us to narrow the search a little. McAra had been speaking on the Custom House steps (or the vicinity of the steps, his preference being to speak without a platform), where there was for many years a range of leftist, religious and rationalist speakers whom workers would gather to hear. The Custom House was fortunate insomuch as it was close to a number of factories, the docks and the shipyard, and was a large and vibrant arena for free speech. Whether McAra simply turned up or was invited (most probably by the completely non-sectarian Clarion movement of Robert Blatchford, who were always interested in a range of leftist views and speakers), is unknown but his visit was remembered for many years after. The basic facts are that McAra made a speech in which he indicated that one could understand why the Tsarist official, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich had been assassinated in Moscow. Local RIC detectives moved in and McAra was arrested, charged and convicted of making a seditious and inflammatory speech and sentenced to three months in Crumlin Road gaol. Mat Kavanagh, who knew McAra, insisted that a ‘nark’ had been employed by the detectives who had him under surveillance in order to trap him into making the statement and McAra fell for it. Belfast Marxists were still referring to it in the 1930s and it evidently alerted many on the left in the city to the tactics police were taking to combat the open-air free speech pitch, after the baton charges and sectarian intimidation campaigns of earlier years had failed to chase progressive voices off the streets.(5)

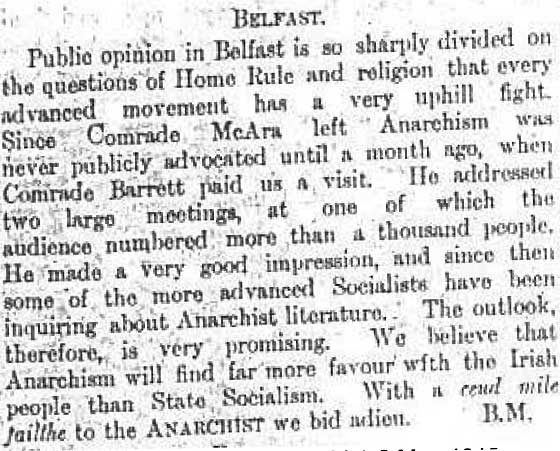

McAra’s time in ‘the Crum’ had a bad effect on his health apparently, and shortened his life by a number of years but his courage and anarchist politics were well received in Belfast. After speaking it was his custom to sell a number of anarchist pamphlets from the pavement and he was more successful than most in this part of his propaganda, always selling large quantities of Bakunin, Kropotkin, Malatesta and others. Despite the cost to his health of the Belfast sojourn, an anarchist group came out of the work and reaching across the North Channel to Scotland, as many in Ulster had done for centuries, they found ready support for their group. The Glasgow anarchists provided further speakers and publicity in their newspaper, the Anarchist, published from 1912 to 1913, and the Belfast comrades appear to have enjoyed a period of growth and stability, something which they themselves attributed to the early labours and example of John McAra, as much as to their Glasgow comrades.(6)

Excerpt from The Anarchist, 3 May 1912

What became of the Belfast anarchists in the years afterwards or what impact they even had on class struggle and the working class in general as militaristic nationalist chauvinism swept over Ulster, Ireland and Europe is an area deserving of serious attention. The left in Belfast was whittled down into opposing factions typified by the James Connolly-William Walker controversy though with both representing a sterile, nationalistic authoritarian socialist vision devoid of libertarian ideals. Anarchists, where they weren’t simply ignored for their tiny numbers, would probably have been seen as beyond the pale by both groups and most other Marxist-inclined writers, thinkers and/or activists of the time. Undoubtedly, however, there were others, not least of whom were probably a good many ordinary workers who were stimulated and inspired by anarchism, anarcho-syndicalism and libertarian, non-hierarchical forms of organising, in struggle and for revolutionary change. If so, John McAra had played an active and important part in that process and deserves a wider recognition for so doing.

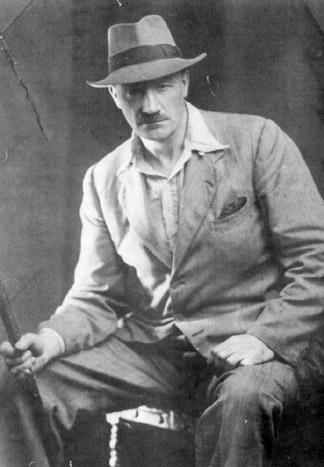

Captain Jack White (1879-1946)

Any study of anarchism anywhere in Ireland would be amiss if it did not include mention of the first organiser of the Irish Citizen Army: republican, communist and then anarchist, Captain Jack White. To date, very little has been written on White’s anarchism, which is deserving of more study, as it did not simply arise out of the Spanish revolution of 1936-7, as is often thought. Although White’s papers have all been destroyed, there remain a few useful sources in relation to his life and activism, and more may yet be found to draw an accurate picture of White the anarchist.(7)

Jack White’s connection, of course, to Belfast is tenuous. He was born at Whitehall, near Broughshane in County Antrim and spent much of his childhood in England before joining the British Army and serving overseas. His inclusion in this study is brief and merited by White’s many visits to Belfast and his eventual death in the city in 1946.

The details of Jack White’s early life are fairly well documented and highlight his relatively wealthy, landed Protestant upbringing, his uneasy transition to a British Army officer and his first major clash with Roman Catholicism over his marriage to a Gibraltarian socialite. The Russian revolutionary uprising of 1905 appears to have had a singular effect on White and he was drawn particularly to Leo Tolstoy the eponymous creator of ‘Christian anarchism’ in the years after that event.(8) The pacifism of Tolstoy probably appealed to White after his experiences of brutality in the Boer War (though this was the only military escapade with which he was involved). Soon afterwards he resigned his commission and left the Army, working for a while in Bohemia and then Canada (as a lumberjack), before moving to England and joining the anarchist commune at Whiteways, near Stroud in Gloucestershire. The settlement was founded in 1897 by a Gloucester journalist named Samuel Bracher (and not, as some have suggested, by an ‘eccentric mid-European nudist’ named Francis Sedlak). The idea was simply to put anarchy into practice in an experimental venture of communal living, free from money and conventional sexual morality. It nonetheless had many moralistic inhabitants – followers of Tolstoy and his writings – who believed in non-violence, vegetarianism, and open-toed sandals, though not always in that order. Later in the 1930s, the settlement operated as a sort of retirement home for anarchist militants and their families, as it had for many years as a holiday resort.9 These sedate surroundings formed the backdrop to White’s embrace of Irish politics around 1912, and he followed the trail-blazing Presbyterian liberalism of Ballymoney’s seminal Protestant Home Ruler, J.B. Armour, in his first ‘outing’ as an advocate of Home Rule in that town in 1913.(10)

Jack White left Whiteways in 1912 or early 1913 for good and after the brief spell in Ulster he moved on to Dublin where he was involved with a small group of progressive intellectuals named the Civic League. The great working class upsurge of the 1913 Lockout was entering a crucial stage and White was an enthusiastic supporter of the Irish Trades and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU), and their strike against the capitalist oligarch and Irish nationalist newspaper baron, William Martin Murphy. White spoke and agitated alongside Jim Larkin and ‘Big Bill’ Haywood of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and initiated the idea and then commanded the concrete organisation of the Irish Citizen Army. This was a worker’s militia, originally the ITGWU at arms in a sense, but something which became under White’s Sandhurst conditioning, a militaristic corps of worker-soldiers, ripe for discipline and orders and, through James Connolly’s influence, pliable in the hands of the military council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in the lead-up to the Easter Rising of 1916.(11)

Convinced as he was of the need for the unification of the labour and national movements, and clashing on this subject with Citizen Army secretary, Seán O’Casey, Jack White moved across to the Irish Volunteers and was dispatched to Derry to train the local corps. This liaison lasted but a short time when he encountered in Derry a strong sectarian antipathy and desire among local Volunteers to fight the rival Ulster Volunteer Force. At the outbreak of war White kitted out a field ambulance and joined an Australian medical force, but lasted only a short time before returning to England. By 1916 he was in south Wales and served three months in prison for trying to organise a strike by miners in opposition to the executions of the leaders of the Easter Rising. In subsequent years, and with a ban on him entering Ireland, White moved more towards a communist position and supported the attempts of the Socialist Party of Ireland to affiliate to the second world congress of the Communist International in Moscow in 1920. Asked to stand on a Worker’s Republican ticket in Letterkenny in County Donegal for the 1923 general election, White said he’d stand instead as a ‘Christian Communist’ and not as a republican which he felt to be a ‘morally and politically unsound’ position. Unready as it was for such politics, Donegal rejected this response from White and he moved on to become actively involved with the abortive Irish Worker League, set up by Jim Larkin also in 1923 after the latter returned from the US. This venture was not a political party, embryonic or otherwise, and began to disintegrate in the wake of the Comintern’s slackening hope in Larkin. Indeed, the Revolutionary Worker’s Group (RWG) emerged in its place in 1930 and won the immediate support of Jack White and a great many ordinary workers. The RWG was yet another communist incarnation, but one that, by its involvement in the unemployed struggle particularly, achieved a heroic if short-lived status in the working class movement.(12)

In 1930, White produced his autobiography. It is a curious and, at times, egotistical account of the man and his political and philosophical development. What comes across most strongly is his fierce independence of thought and action, his ironical self-effacement and his strong Ulster Protestant heritage. What remains behind is largely half a picture, insofar as the culmination of White’s political development towards anarcho-syndicalism is not included, coming as it did, in the later 1930s after his visit to revolutionary Spain. Fortunately, however, and thanks to the efforts of Belfast’s contemporary anarchists, a re-print of White’s pamphlet, The Meaning of Anarchism, published in 1937 has left us a strong sense of his anarchist ideas. He wrote, for example, ‘to destroy the state, one must not begin by becoming the state; for in doing so one becomes automatically its preserver’. Instead, he held, that to abolish the state and class society non- hierarchical, bottom-up self-organisation was the only way forward for the working class, and anarcho-syndicalism in Spain had shown that way. This was because, ‘anarcho-syndicalism applies energy at the point of production; its human solidarity is cemented by the association of people in common production undiluted by mere groupings of opinion’.(13)

Jack White returned to Belfast in 1931, and as in Dublin nearly twenty years previously, signalled his support for the unemployed demonstrators of East Belfast with a vigorous physical assault (this time minus a hurley stick) on the police who were trying to break up the protestors. White was in East Belfast in solidarity with the unemployed and as a member of the RWG, and spent a month in prison for his defence of the street protest. More damaging was the exclusion order served on White as he emerged from Crumlin Road gaol, and which effectively put an end to his political activity north of the border.(14)

Apparently, Jack White went to Spain in 1936 with a British Red Cross unit, though anarchist comrades who actually knew and remember him, state fairly categorically he had some connection with the famed ‘Connolly Column’ section of the International Brigades, which sailed from Ireland to fight fascism in 1936. They further state that there was a clash then between Frank Ryan, a leading Connolly Column member, and White. The left republican-leaning academic Ferghal McGarry is quite critical of this view and the memory of White’s contemporary, Albert Meltzer in particular, in relation to it. He further feels Meltzer is too harsh on Frank Ryan for collaborating with the Nazis soon after the Francoist victory in Spain.(15) Without an examination of the papers of the ‘Freedom’ Group with which White was connected in the years leading up to his death, it is difficult to be definitive about how White went to Spain and what dealings he had with the ‘Connolly Column’. We do know he became thoroughly disenchanted with Stalinist communism and aligned himself firmly with the Spanish anarchists of the CNT-FAI, and on returning to London set up an arms smuggling enterprise to the anarchists via Czechoslovakia and Germany. Meltzer, who himself had a family connection with Ballymena, helped out in this enterprise by ‘invoice typing and listening to White endlessly relating the crimes of the Catholic Church’.(16) The channel was closed down, however, when the Germans alerted London about this surreptitious breach of the Non-Intervention Pact, and the Captain confined himself to activism with the pre-war Freedom Group, arbitration amongst the divided anarchists of Glasgow, and the production of an Irish anarchist labour history survey with the Liverpool Irish anarchist, Mat Kavanagh. Finally, in 1940, it was only in illness and death that exile ended for Jack White and after a brief period in a Belfast nursing home, he died and was buried in the graveyard adjoining Broughshane First Presbyterian Church.(17)

Jack White’s journey towards anarchism began many years before his embrace of nationalism or communism, and although his conversion to anarcho-syndicalism came later, his libertarian ideas were the defining political motif of his life. He had, since boyhood, already carried a total detestation of the villainous and shameless tyrannical hypocrisy and doublespeak of the Roman Catholic Church, as a set of ideas completely without rancour or bigotry towards individual Catholics. His subsequent experiences of the de-humanising authoritarianism and barbarity of the Army and war set him on a path that never thereafter veered too far from a solid libertarian socialism.

1. Emmet O’Connor, A Labour History of Ireland 1824-1960 (Dublin, 1992), p.35.

2. New Register House, Registrar General’s Office for Scotland, Census of 1891, District of St. George, Edinburgh, 161 Fountain Bridge, Edinburgh, 685/01/073/000/016.

3. Freedom, May 1934.

4. Florence Boos, ‘William Morris’ Socialist Diary, edited, annotated and with an introduction and biographical notes’, in History Workshop Journal, Issue 13 (Spring 1982), p.70; and Freedom, May 1934; and John Taylor Caldwell, Come Dungeons Dark (Barr, 1988), p.107.

5. Freedom, May 1934; and Caldwell, p.106; and Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI), Home Affairs, Royal Ulster Constabulary, Special Branch Files, report dated 30 April 1930, HA/30/1/545, reference to ‘McArrow’, sentenced to 3 months for seditious speech, by Loftus Johnson, member of the Belfast Revolutionary Workers Group; and O’Connor, pp.62-3.

6. Freedom, May 1934; and Haia Shpayer, ‘British Anarchism, 1881- 1914: Reality and Appearance’, Unpublished PhD thesis, University of London (1981), p.106.

7. Jason Brannigan, ‘Jack White: From Loyalism to Anarchism’, introduction to Jack White, The Meaning of Anarchism (Belfast, 1998); Alan MacSimóin, ‘Jack White’, http://struggle.ws/ws/ws50_jack.html; and Ferghal McGarry, Irish Politics and the Spanish Civil War (Cork, 1999), are the only three works to look at White relative to his anarchism, although Kevin Doyle’s work also deserves mention, see http://struggle.ws/anarchists/jackwhite.html. His RUC Special Branch file (looked at by McGarry) may be of use along with other Branch files and documents in the Spanish Interior Ministry’s archives.

8. Andrew Boyd, Jack White, First Commander, Irish Citizen Army (Belfast, 2001), p.9.

9. John Quail, The Slow Burning Fuse: The Lost History of the British Anarchists (London, 1978), pp.228-9. Boyd makes the mistaken assertion about Sedlak, possibly because White’s first letter from Whiteway had ‘care of Francis Sedlak’ written on it.

10. Boyd, pp.10-12.

11. Boyd, pp.15-26; and Brannigan, p.1; and O’Connor, pp.87-93.

12. Boyd, pp.27-38; and Jack White, Misfit (London, 1930), pp.310-12; and O’Connor, pp.122-26.

13. White, Misfit; and Brannigan, pp.3-4. 14. Boyd, pp.39-40; and Mike Milotte, Communism in Modern Ireland: the

Pursuit of the Workers’ Republic since 1916 (Dublin, 1984), p.127.

15. McGarry, p.71 and p.271, note 59; and Albert Meltzer, The Anarchists in London, 1935-1955 (Orkney, 1976), p.14; and Albert Meltzer, I Couldn’t Paint Golden Angels (London, 1996), p 57.

16. Meltzer, I Couldn’t Paint Golden Angels, p 58; and Brannigan, p.2; and Boyd, pp.41-2.

17. Caldwell, p.232.