Making Policing History: Studies of Garda Violence and Resources for Police Reform

These texts are written and edited by the Garda Research Institute which is composed of residents, community workers and educators who have both personally experienced Garda violence and have heard countless negative stories about the gardaí. They came together to examine the role of the gardaí and in particular to spark debate and discussion about who gets targeted by the police and why.

These texts are written and edited by the Garda Research Institute which is composed of residents, community workers and educators who have both personally experienced Garda violence and have heard countless negative stories about the gardaí. They came together to examine the role of the gardaí and in particular to spark debate and discussion about who gets targeted by the police and why.

The text is structured in the following way. Following the introduction and a piece on the making of the gardaí, the pamphlet is divided into three sections, the first of which looks at the experience of the policed. The next section looks at the policing of protest by the gardaí. The final section looks at responses to policing and examines how grassroots activists and movements have attempted to make the police more accountable.

For ease of reading you can download a PDF of the entire text in A4 format or fold over A5 format.

Introductory

- Why we put this pamphlet together: secrets, lies and unaccountable policing

- How the gardaí were made

On the receiving end: experiences of being policed

- Working-class experiences of the Gardaí

- Terence Wheelock: looking for justice

- The prisoner who disappeared… for a while

Political policing: the gardaí and democracy

- I still remember my first time

- Reclaim the Streets 2002: a police riot and the aftermath

- Resisting Shell in Mayo and the experience of policing in Erris: an eyewitness account

- Policing the anti-war movement

- When do the police get away with violence, and why?

- From force to fencing: political policing in the Republic of Ireland

Responding to abusive policing: practical resources

- Challenging the gardaí: a personal experience

- The Prisoners’ Rights Organisation: a historical case study in grassroots organising, “history from below” and police accountability

- Challenging targeted policing: my experience in the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty

- Making policing history: different ways of resisting

Appendix

Reders experiences & comments

For ease of reading you can download a PDF of the entire text in A4 format or fold over A5 format.

Return to the index page of Make Policing History

Leave us a comment or share your experiences

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| PDF of this Policing Pamphlet at A4 size | 1.2 MB |

| PDF of this Policing Pamphlet for A5 fold over size | 1.46 MB |

Why we put this pamphlet together: Secrets, lies and unaccountable policing

It really does not take a lot of effort to come across anecdotal evidence of insensitive and sometimes brutal policing in working class areas in Ireland. As residents, community workers and educators in a wide variety of settings we have both personally experienced Garda violence and have heard countless negative stories about the gardaí. These stories cover a wide range of issues. Most consistently people, usually but not exclusively young men, complain of insults, intimidation on the street and of physical violence during arrest and in custody. The violence they describe is of varying degrees of seriousness and routinely involves minor assault (e.g. slaps, kidney punches and limb twisting etc) but more serious violence can and does occur (1).

To add insult to injury, the gardaí will then pre-emptively charge people with assault after beating them up. In cases of violence against minors, we have heard convincing stories of parents being allowed to pick up their children only after signing a statement to the effect that no harm was done to them while in Garda custody. We have also repeatedly been told that the gardaí indiscriminately use drugs laws to stop and search people and arbitrarily use public order legislation to charge people they have decided for one reason or another need to be ‘taught a lesson’. The dismal similarity and frequency of people’s accounts of mistreatment can lead you to only one conclusion-that something is rotten with policing in Ireland.

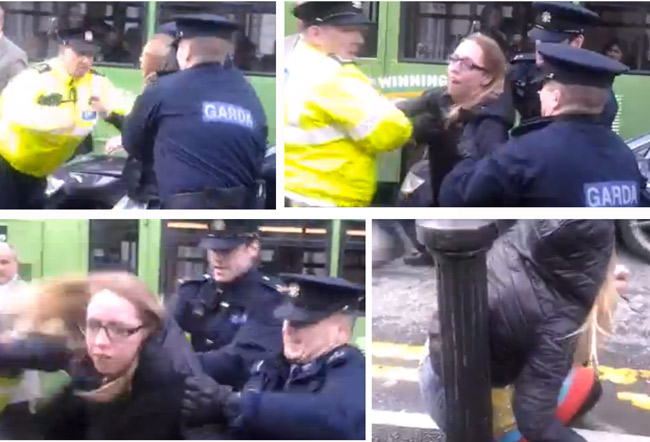

Similarly, as activists involved in ecological, anti-war, anti-capitalist and social justice movements we have come across innumerable stories of Garda misconduct. We all know, again through personal experience, that harassment, surveillance, intimidation, trumped up charges and beatings are a part, albeit a small part, of being an activist in Ireland. The police riot at Reclaim the Streets on Dame Street in 2002 or the violence directed at residents and supporters in Rossport are simply the most visible part of what in the case of any other institution would be called a culture of violence.

We think the disparity between what gets said in private and what gets said in public about the gardaí deserves serious consideration. However, it is impossible to know just how widespread this sort of policing is across the country (2). One thing which can be said about the gardaí in particular is that - unlike a number of other European countries - there have been no whistleblowers, even among the large number of those who have left the force. It is not clear whether this is because individual acts of violence and intimidation are accepted by other officers, or because those who dissent fear the kind of reprisals that “civilians” who challenge police abuse routinely experience.

What is clear, and what is significant, is that these abuses of power in working class communities and against activists remain largely invisible. Perhaps this invisibility should not come as a surprise in a country so burdened with secrets and lies. After all we know that that we live in a State in which a whole world of experience - of poverty, institutional violence and disrespect - has remained largely hidden for decades. We know that powerful people have the ability to impose silence on ordinary people and we know that uncomfortable truths can remain hidden for decades.

It is in that spirit that this editorial collective came together to examine the role of the gardaí in the shadows of the Republic. In particular, we want to spark debate and discussion about who gets targeted by the police and why. We want to break the silence about Garda brutality and misconduct and to create space for people to tell their stories in their own words. We also want to understand how the silence about the gardaí is maintained, be it through coercion, ignorance or shared illusions. Above all we want to identify resources and realistic strategies for making the police accountable through grassroots activity.

It is important to stress however that this pamphlet is not interested in making simplistic arguments or claiming that all police are malicious and doltish. They are not. Cartoon accounts of ‘goodies and baddies’ serves no-one, least of all those who are interested in social justice and equality. On the other hand neither do we think that abuses of power are simply the work of a few ‘bad apples’: they are too systematic, too similar and too unchallenged for this to be believed. The point is to begin to trace in an accurate way how power and policing function in Ireland and why.

This pamphlet is a modest attempt to open up a public conversation about these issues. Of course it has many gaps. There are many other examples of abusive policing that could be added to the stories in this collection. In particular, we are missing material about the policing of strikes and labour disputes, republicans, travellers, migrants and the LGBT community: if this pamphlet makes it into a second edition, we hope to plug some of these gaps. We are also aware of our failure to address another major part of the story – the development of state repression, including the diminuition of public rights of assembly and protest through legislation such as successive Criminal Justice and other Acts. Another are of inquiry missing from this piece which we would hope to return to is that of future directions of policing towards privatisation, militarisation and internationalisation. We also hoped to talk to gardaí about their perspective on crime, punishment and power but unfortunately this also proved impossible.

Social class and policing

For us the disparity between the public and the private conversations on policing in Irish society reflects broader social inequalities in power and wealth. Firstly, the gardaí are a powerful, influential and well established group in Irish society and their activities have rarely been scrutinised (until 2007 the only body tasked with investigating any allegations of abuse was the Garda Síochána itself) (3). As in previous generations with challenges to priestly power, those who raise questions about Garda behaviour meet with aggressive responses by those who feel that the gardaí should be above any public accountability. In particular, many well-off people and people from rural communities evidently see the gardaí as serving their interests against those of working-class urban people and political activists. Media willingness to accept Garda accounts of events confirms this sense that all respectable people should line up behind the police - and that it is inconceivable that the police should ever behave badly.

Secondly, and most importantly, the people who are most likely to experience police brutality, coercion and intimidation are young working class men. This affects what gets reported, not only because such young men lack the resources and influence to kick up a stink about Garda misconduct but also because the media is by and large far more attuned to the social experiences, needs and sensitivities of the middle class. Furthermore, from the point of view of the young men who end up dealing with the police on the streets or in cells, it is simply common sense that complaining about the gardaí may cause more trouble for them in the future. They also know that in most official and judicial processes they are less likely to be believed than the gardaí.

Thirdly, and this is less widely discussed than the other two issues, within working class communities people typically find themselves in a bind with regard to policing, which means that some issues regarding the behaviour of the police are often not tackled in public. On one hand people know only too well about the cost and impact of crime and the numerous social problems caused by deprivation and inequality. Most people have had to deal with the consequences of this on a regular basis while trying to get on with life in an honest and decent manner. They also know how complex these issues are on the ground and understand that the police often have a difficult job. But they have also found that the police are often not there when they need them, and that serious social problems are ignored and overlooked. To make matters worse this general absence of policing is often punctuated by aggressive barracks-style policing in which gardaí, who often culturally share little in common with the people they police, chose to treat all locals as potentially disorderly and criminal. To further complicate things, living in places which are often seen by outsiders simply as ‘problem’ areas makes any discussion of policing in a working class area a loaded issue. People quite rightly resent their communities being represented in the dull monochrome of journalistic clichés which treat working class areas as hotbeds of crime, drugs and anti-social behaviour. Understandably this leads to a wariness about anything that would contribute to making a place seem less respectable including tackling police misconduct.

All these issues – a lived experience of crime and social problems; sensitivity about how an area is perceived from the outside; long periods of lax policing followed by bursts of aggressive policing- combine to make crime and punishment a very sensitive and potentially divisive issue in working class areas. Ultimately, this fosters a real ambivalence about how to deal with the gardaí and how to negotiate the questions of brutality and accountability.

Political policing

The working class is not the only group to be on the receiving end of prejudiced policing. Stigmatised minority groups such as Travellers, asylum seekers, refugees and Roma can often be at the sharp end of police activity, as can such groups as punks, ravers and new age travellers.

While all these groups share in a somewhat ‘marginal’ social position, groups which are in no way marginal can also end up bearing the brunt of police tactics also. For example, when the white-collar workers at Thomas Cook in Dublin decided to protect their jobs by occupying their offices in August 2009, 150 gardaí removed and arrested them in an early morning raid on the occupied offices: here a respectable group passed over into the realms of ‘unrespectable’ or ‘unacceptable’ behaviour. A similar, and much stronger, example of this is provided by the policing of Erris, a traditional rural community which would normally by unproblematic in terms of policing, which now lives under something close to Garda occupation, where there are often more gardaí than residents, due to the community’s opposition to a dangerous gas pipeline and refinery.

In both of these cases, the gardaí appear to have been operating as the bully boys or armed wing of the capitalist class, operating either to protect the projects of individual capitalist companies or the more general forms of operation or discipline of capitalist society. In relation to the Thomas Cook strikers, this is of course only one example of a long line of strikes where the gardaí intervened on the side of the bosses: regrettably this is an issue that has been neglected by labour historians (4). The Erris example is a more intense and long-term involvement by gardaí in the imposition of locally unwanted land uses on recalcitrant communities, which had been preceded by Garda assistance in the erection of telemasts and the dumping of asbestos waste (5).

These examples bring us to the second major type of policing this pamphlet examines, protest policing or political policing. Here we again come across similar problems to those mentioned above regarding the policing of the working class. Political groups which are on the receiving end of police harassment and interest are normally marginal ones, and those that aren't are easily portrayed as being led astray by 'outside agitators' and troublemakers of various kinds. The issue of political policing is complicated in the Republic by the ‘shadow of the gunmen’, the existence since the foundation of the state of an armed military and political organisation which refused to accept the 26 Counties as a legitimate state. While there have been occasional scares about communists or revolting workers, the main concern of the political police over the entire life of the state has been the Republican movement. This is an issue that we don't address in this pamphlet, partly because none of us working on this pamphlet are republicans, partly because it is an exceptional issue requiring its own analysis, and partly because such analysis of political policing in the Republic as has been carried out has centred on state treatment of republicans. Still, many of the tactics that the gardaí have used in response to the republican movement are carried over into their policing of other political conflicts. The general trend appear to be towards a worrying over-policing of protest and a diminuition of the right to protest based on a view that sees most protest as ‘subversive’. Anti-republicanism is convenient to the Irish establishment in much the same way as anti-communism was to the US establishment; the mere allegation that republicans are involved in a movement is enough to smear it in the eyes of many and to legitimate almost any behaviour on the part of police.

Overview of this pamphlet

The pamphlet is structured in the following way. Following this introduction and a piece on the making of the gardaí, the pamphlet is divided into three sections, the first of which looks at the experience of the policed. We begin with an account of the experiences of working class men and youths, who are considered to be guilty until proven innocent, with garda harassment and disrespect. This is followed by discussion of the experiences of the family of Terence Wheelock, a young man from inner-city Dublin who died under mysterious circumstances in Store Street garda station. The final piece in the first section details the removal of a prisoner's rights without explanation on Garda say-so. The next section looks at the policing of protest by the gardaí, beginning with an activist’s account of the attentions of the Special Branch (the political police) coupled with a personal account of how the garda and military occupation of northwest Mayo to protect Shell's right to Irish natural resources has attacked a traditional rural community and an overview of police responses to opposition to US military use of Shannon. These accounts are followed by two more analytical pieces, the first of which is an examination of the way the gardaí attempt to redefine protests as violent, and when they do (and don't) get away with it. This section ends with a broad overview of protest policing in the Republic from the 1960s to date.

The final section looks at responses to policing and examines how grassroots activists and movements have attempted to make the police more accountable. It begins with two personal experiences: one of challenging the gardaí through the available machinery of the Garda Siochana Ombudsman Commission, and one by a victim of the police attacks on Dame Street at Reclaim the Streets in May 2002, detailing their attempts to obtain justice through the courts. These are followed by two accounts of organised responses, one by the Prisoners' Rights Organisation in Dublin in the 1970s and 1980s and another by the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty, which brings a welcome perspective from abroad to the pamphlet. The section finishes with a survey of different methods of putting manners on the police. The pamphlet ends with a list of resources and information sources for those interested in the issue of policing.

The articles printed below involve a wide range of approaches, varying from people recounting their personal experiences to more analytical and ‘academic articles’. Some articles – such as that on the PRO - involve the recovery of a hidden history of organising on issues of police power and abuse in the Republic; others outline ways in which police powers are being abused in contemporary Ireland. Taken together these articles tell an untold story from a country in which it is almost impossible to bring the gardaí to court with any hope of an positive outcome and where critical media scrutiny of the gardaí is extremely rare.

In the nature of things, the aggressive and ‘dirty tricks’ response by gardaí to critical observation, and the barracks culture which has prevented whistleblowing even by past members of the force, makes it difficult to ascertain facts in the way which becomes possible for other professions when they are the subject of serious legal, journalistic, academic and activist scrutiny. Nonetheless every effort has been made to be as accurate as possible, to double check facts and to avoid exaggeration, which serves nobody.

In conclusion

We are well aware that we have only scratched the surface of this topic. There obviously is a need for a more comprehensive and more developed analysis of the history and practice of policing – of both political protest and 'ordinary decent criminals' - in the Republic. This will need to address not only examples of Irish ‘exceptionalism’ - for instance how the the Republican movement was policed - but also the ways in which the Irish experience tallies with the international experience of policing. We see this pamphlet as being the first step along the road to the development of such an analysis.

When we began this project we had a variety of questions we wanted to answer: what is the difference between political policing and ‘ordinary, everyday policing? What are the connections between the gardaí and the Irish state and at what levels are decisions on policing made? Is it possible to extricate the useful aspects of policing – ‘keeping the peace’ responding to domestic violence, etc. - from the more general disciplinary role of the police in a capitalist society? Just how different is ‘community policing’ from state or private policing? What separates community self-policing from vigilantism and who decides who is a vigilante?

It quickly became obvious to us however that much basic work on policing in the Republic needed to be done before we could even think about addressing these questions, as the lack of analysis of policing in the Republic was stunning. Thus we scaled back our ambitions and this pamphlet is the result: a mixture of accounts and analyses of various experiences and types of policing in the Republic, which, with all its gaps, represents a first step towards a more general account and analysis. As such this pamphlet is an invitation to others to respond to this collection - to criticise, discuss and analyse its contents as part of a broader effort to understand Irish policing.

WORDS: Garda Research Institute

For ease of reading you can download a PDF of the entire text in A4 format or fold over A5 format.

Return to the index page of Make Policing History

Leave us a comment or share your experiences

1. We have personally come across several accounts of very serious assault and injuries during arrest and in custody. In preparing the publication we were told about at least half a dozen cases some of which damaged people psychologically. It should also be noted here have been 28 deaths in police custody over the past decade: see http://www.tribune.ie/article/2010/jul/18/twenty-eight-deaths-in-garda-c.... There have been several cases such as the deaths of Brian Rossiter, Terence Wheelock and John Moloney which have given rise to serious concerns about violence in custody.

2. One of the few indications, which may or may not be representative, is that over 2000 complaints a year have been logged with the Garda Ombudsman since it was established in 2007. Surveys completed on behalf of the same body found 1 in 20 people have had reason to complain about the gardaí. It should be borne in mind that research suggests that young working class men are less likely to make complaints (see paper by B. Moss at the Sociological Association of Ireland Postgraduate Conference, 2009). A poll in the Irish Times published on February 10th 2004 discovered that 37% percent of people do not have confidence in the Garda.

Another indication is the level of payouts by gardaí to their victims, which has become so systematic as to substitute for court cases. The system also represents a tacit recognition that Garda victims can expect no justice from the courts. In 2007, for example, the force paid €14.7 million in compensation (see http://www.tribune.ie/archive/article/2008/sep/07/garda-wrongdoing-costs...). 2007 was a particularly “bad” year in that the Donegal corruption case was being processed, but as far as can be ascertained compensation payments have always run to at least several million euro annually through the first decade of the 21st century. In the second half of 2009 and the whole of 2010, payments linked to garda misbehaviour or negligence alone totalled €7.7m (http://www.tribune.ie/news/home-news/article/2010/dec/05/state-pays-4200...). Cases included 18 garda assaults in 2009 alone, 6 cases of abuse of garda powers (in some cases relating to misuse of the Pulse computer system), as well as other payments for defamation, negligence, nervous shock, miscarriage of justice and malicious prosecution.

3. Unsurprisingly they rarely discovered problems with the way policing functions. The Garda Ombudsman, modelled partly on reforms in the north of Ireland to the PSNI but with much more limited powers, was created in 2007 as a supposedly independent oversight and complaints body.

4. For example the first 25 issues of the Irish Labour History Society journal Saothar (http://irishlabour.com/?page_id=205), while containing two articles on Dublin police in the 19th century, (one on working conditions, another on the 1882 police strike), have no coverage of the policing of labour disputes in the Republic.

5. This example also brings up another issue we don’t touch on - who decides what is a crime? After all, long term exposure to a fatal poison if it occurred on an individual basis - say a wife administering cyanide to a husband in his food over a long period - would be criminal, yet exposure of communities to toxic chemicals and highly hazardous processes isn’t considered a crime. Impoverishing communities to the extent where deaths by heroin are a routine part of most families’ experience is not criminal; even minor thefts by those living in such communities is (and until recently could leave minors incarcerated in industrial schools and subject to violence sanctioned by state and church).

How the gardaí were made

There is something mystifying about the police force in the Republic of Ireland. A force born out of a bloody civil war yet strangely absent from popular memories of those long years of violence. A force celebrated for its rootedness in Irish cultural practices yet operating in the same centralised, colonial model inherited from the Royal Irish Constabulary, the police force of British state. An institution complicit in the abuse and degradation of children, of mothers, the poor and destitute yet somehow the guard continues to command respect and solidarity in Irish society while increasingly the priest or the politician are looked on with scorn and disgust. What is it about the Irish police force that enables it to continually overcome periods of controversy over abusive practices? Or perhaps this is not the right sort of question at all. Maybe it is that there is something distinct about the way Irish society works that facilitates an acceptance of violence by the state toward a particular type of person or group of people. The first step toward unravelling these complicated questions must begin with developing an understanding of the historical conditions in which the gardaí emerged.

Colonial beginnings

It is difficult to imagine a society without a police force and if you were to ask someone to try they would probably list off all the terrible things that would unfold without officers of the law ready to enforce order. Policing has become so naturalised that it is hard to believe that there was once a time when state policing didn't exist. Policing and the modern state are recent inventions conjured up to ensure the security of capital and to enforce wage labour as feudalism unravelled and wealth and power reorganised into state and market rule but that is another story for another day. Suffice it to say that there was once a time when law and order as dictated by the state and enforced by the police did not exist. This is not to say that prior to the emergence of state policing there was no enforced order. Rather there was a shift, beginning approximately around the 16th century, away from order as dictated by the feudal lord, the monarchy and the church to a centralised and militarized order operating at a national level and dictated by the state in the interests of a newly emergent capitalist class.

The first attempts to legally consolidate order as dictated by the modern British state and enforced by the police got off to a shaky start when the policing bill was turned down in the British parliament in 1785. Although policing under the absolutist state had been in operation for over a century at this stage, enacting brutal and bloody legislation which forced people off common land and from subsistence living into a condition of poverty then pushing them into wage labour, the late 18 century was a time when the political and capitalist classes, who had by now consolidated their power, were seeking to sanitise the recent history of the state. The establishment of a modern police force under the liberal democratic state would have to wait until popular perception of the police could be changed. But politicians and social theorists intent on manifesting their vision of social order were not dissuaded and the modern policing experiment was sent overseas to be tested out on Irish soil. Historians have argued that the political and social conditions of popular protest and agrarian unrest rampant throughout Ireland at the time served as a social laboratory in which modern state policing was first developed (Palmer 1988; Burn 1949).

The Dublin Metropolitan Police were the first police to hit the streets in Ireland in 1786, followed by the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) in 1814. They had their work cut out for them as anti-colonial rebellions were sweeping the country. Growing labour movements in urban regions and agrarian groups in rural locations were organising workers and enabling resistance to evictions and defending tenant farmers. By 1836 the RIC, an armed, centralized and militarised constabulary, had a nationwide presence and just 14 years later police numbers had increased to 13,000 in 1,600 barracks, three times more police than in England. A paramilitary model of policing, tested out and developed under the RIC, would be exported to British colonies worldwide while on English soil efforts continued in an attempt to generate consent for policing. Popular identification with officers of the law was facilitated through a recruitment strategy which drew on a range of social backgrounds and through linking together police culture with the values of an emergent British cultural nationalism. This practice of achieving consent for state policing through association with an imagined common national cultural became a key practice in state building projects internationally and police officers, particular in the UK, have become the symbolic currency of the nation state. These measures, along with a decentralised organisational structure, were successful in changing the perception of policing held by the liberal political classes and the press, and the London Metropolitan Police Act was passed in 1829.

Back in Ireland, anti-colonial struggle was spreading. The Home Rule movement rose throughout the late 1880’s popularising the politics of self-determination while at the cultural level projects such as the GAA, the Gaelic League and the Celtic revival associated with the nationalist movement developed into institutions of Irish cultural nationalism. During this time the RIC and DMP increasingly became targets for groups refusing to be governed by the British state particularly after the brutal repression of the 1916 Easter Rising. Resistance to the force became policy in Sinn Féin’s 1919 Declaration of Independence, which declared a boycott on the constabulary and launched the guerrilla war of the IRA. At this point the Republican movement set up a parliament, court system and policing body, the Irish Republican Police (IRP) which operated from 1920-22 providing security and enforcing the judgements of the Dáil courts. The IRP were treated as an illegal subversive group by the British State and the RIC set about wiping out the republican policing body, but their numbers had been greatly depleted by sustained attacks from the IRA. A large number of veterans from the First World War signed up following a recruitment drive in Scotland and England and were shipped across the sea to combat the growing Republican movement. The RIC auxiliary police force became known as the Black and Tans, a notoriously brutal military force. A ceasefire between the IRA and the British State was agreed in 1921 followed by the Anglo Irish Treaty which established the Irish Free State as a dominion of the British Empire excluding six counties in the North of the country, decisions which split Sinn Fein in 1922, and the authorities of the new state turned their attention to governing and policing the new state.

Policing the Irish Counter-Revolution

The new police force would play a central role in the counter-revolution of the emerging political order as the armed forces of the Free State turned against former allies. Clashes increased between anti treaty republicans and nationalists who supported the provisional government, led by Cumann na nGaedheal (6), a newly formed party of pro- treaty Sinn Féin members headed by W.T. Cosgrave. Cosgrave declared martial law in 1922 stating that he was willing “to exterminate 10,000 republicans” if it was necessary to achieving order (Vaughan and Kilcommons 2008). The first step to develop a police force was taken by Michael Collins who initiated the “Oriel House men” or Criminal Investigation Department, a Special Branch of armed officers who set about gathering information on opponents of the Treaty, a majority of the IRA at the time (7).

Over the first years of the new state 11, 480 republicans were interned (8) without trial (Maguire 2004) and 150 were executed (Vaughan and Kilcommons). The Free State government decided to disband the RIC but retain the services of the DMP, a police force with a bloody history of crushing union and republican movements (9), while the Royal Ulster Constabulary would take over policing the six counties in Northern Ireland (10). The Police Organisation Committee, staffed mostly by DMP and ex RIC officers, was set up next to develop proposals for a new police force. Plans for the ‘Civic Guard’ took shape, a force almost completely identical to the RIC in structure and recruited in secret to ensure loyalty to the Treaty. This was a deliberate move by the new government to inhibit local control over the formation of the police force, retaining a colonial, centralised and military structure in which the police commissioner would be under direct control of the government who continued to be legally bound to the British State until 1949.

What has conventionally been viewed as the 1922-23 Irish Civil War was in fact a much longer process. Historian John Regan has argued that the period should be recognised as a counter revolution, a period in which, “disparate powers emanating from within a revolution [were] reeled in and controlled by a central authority […] when former revolutionary leaders resort to repression to counter those who persist in using violence against the state”. The counter revolution of the Free State continued into the next decade in the form of a policing strategy designed to crush opponents of the treaty through information gathering, internment and executions.

Rebranding the Civic Guards

The Civic Guard were officially launched in 1922 but half the population did not support the Treaty, the Free State or its related institutions so policing under the new state did not have public consent. External resistance to the force and internal conflict over the leadership of ex RIC officers compelled the initiation of program of changes designed by O’Higgins, Minister for Justice and O’Duffy, Chief of Staff of the IRA before becoming Garda Commissioner in 1922. These changes would reconstruct the image of the force, carving out a space for the police of the Free State on a cultural level. O’Duffy’s vision of this new force was informed by his strong ideas on discipline and order fused with an ethos of nationalism and idealism influenced by his admiration for Mussolini’s fascist corporatist state. A series of changes to the Civic Guard gradually embedded the police in community life shaping the image of the police as “Irish in thought and action” (11).

The first step taken was to disarm the guards. O’Duffy explained his rationale for this decision; “The Civic Guard will succeed not by force of arms, or numbers, but on their moral authority as servants of the people” (Walsh, 1998.) While this decision has created an image of the Irish police as a reluctant coercive institution, a number of points must be clarified about the unarmed status of the Irish police. To begin with, the decision to remove arms was taken following a mutiny within the force in which civil guards, rebelling over the promotion of ex-RIC officers, took control over a stockpile of weapons and forced Collins to remove the men from official duty (Allen 1999). Disarming guards who would challenge decisions at senior level and arming those whose obedience could be guaranteed would weaken the threat posed to the political elite by internal dissent within the police force. The armed guards, officially titled ‘The Special Branch’, have retained a strong presence and maintained quite a degree of unquestioned, discretionary power throughout the history of the Irish state while policing by unarmed gardaí has followed a policy of violence and brutality rather than law enforcement. The Irish police have come to be known – among those on the receiving end and experienced professionals - for not being shy about behaving violently on duty, “opting for rough and ready justice instead of prosecution” (Vaughan and Kilcommons).

The 1923 Garda Síochána Act officially renamed the force to the Irish translation currently in use today, which means ‘Guardians of the Peace’; as part of police training recruits were taught the Irish language. The 1924 Disciplinary Regulations demanded a strict rule of abstinence combined with a respectable salary. At a time of impoverishment this gradually changed the local perception and social standing of the police and applications to join increased. Over the following years An Garda Síochána would develop a strong commitment to sporting practices, in particular the GAA, which stood as one of the largest cultural institutions within the state; the gardaí would “play their way into the hearts of the people” (Brady). In 1952 98% of recruits came from Catholic backgrounds and could be seen marching to mass on Sunday mornings (Mulcahy 2008). The rural and agricultural background of the force was epitomised by O’Duffy as the ideal of the new nation state; he proclaimed, “the son of the peasant is the backbone of the force” (Allen). The success of this cultural programme can be seen in the status of An Garda Síochána as one of the principal ‘in-groups’ of Irish society (12).

Pacifying the ‘Free State’

These symbolic changes and adoption of cultural practices gradually won over public consent for the Gardaí. At the same time a continued program of counter revolutionary policing set about eliminating opponents to the emerging order. The Special Branch, an armed counter insurgency unit, had merged with the DMP in 1923, eventually joining up with the Garda Síochána in 1925.

The new police force emerged under a state governed by the conservative Cumann na nGaedheal party who placed great emphasis on law and order during a time of social unrest while working to naturalise its claim to power through suppressing those who opposed it. Following the withdrawal of the army in 1923, the gardaí had full responsibility for this task.

Battles waged between the gardaí and the IRA as De Valera, having left Sinn Féin to set up Fianna Fáil in 1926, toured the country mobilising support for armed struggle against the Free State. De Valera led Fianna Fáil into the Dail in 1927 and into government in 1932 dismissing O’ Duffy as Garda commissioner, who was replaced by Eamonn Broy, and rapidly moved to distance himself and his new party from armed struggle. Broy recruited several hundred ex IRA men, nicknamed the ‘Broy Harriers’, into the armed auxiliary Special Branch of the gardaí and they swept the country rounding up members of the IRA who refused to support De Valera in a partitioned state.

A combination of grinding poverty and the brutal practices of the Special Branch shifted support away from Fianna Fáil initially to the Blueshirts (13) and later toward a resurgence in IRA activity (Brady). A continued programme of internment without trial was made policy in the 1939 Offences Against The State Act as means to counter this opposition. Clashes increased between the gardaí and the IRA again in the early forties but subsided through a combination of intelligence gathering, military tribunals, executions, economic exile and the internment of over 500 republicans (Maguire). The Southern State responded to an IRA attempt to rebuild the republican movement in the North in 1957 by rounding up hundreds of republicans who were interned in the Curragh military prison in 1958.

The Irish counter-revolution was a battle over the legitimacy of tactics. State authorities claimed a monopoly over the use of violence, framing its opponents as illegal and terrorist. “The dominant nationalist parties defined their opponents as criminal, anti-democratic, and illegitimate not as accurate descriptions but in order to bolster their own claims to legality, democracy, and legitimacy” (Regan).

From policing the state to policing the nation

Since its formation the gardaí have served a dual purpose for the state. On the one hand they suppress dissent to the political order, while on the other they play a central role in the construction of an image of a unified nation and the culture of that nation. The consolidation of political, economic and cultural power took place under the Free State simultaneous to a knitting together of institutions of Irish cultural nationalism and the gardaí were as central to these processes as the Catholic Church, the GAA or Fianna Fáil / Fine Gael. The values of the new order were socially conservative, preserving unequal socio-economic structures and the power of the church, concentrating political and economic power in the hands of an emerging Irish elite at a time of authoritarian social control.

Although the political culture of the time had the image of being divided over the Northern question, in practice the main political parties of the state, Fianna Fail and Fine Gael, could be defined more by consensus than conflict when it came to the conservative nature of their ideology; “majoritarianism, parliamentary democracy, constitutional procedure, church state relations, the rights to private property and the rights of the individual” (Regan). Political revolution had changed the names of those in rule but there had been no social revolution to change material divisions. Society continued to be divided unequally along class lines but this was disguised by an illusion of a unified nation under the Southern state. In reality divisions between those who materially benefited from the struggle for independence and those who did not were identifiable in the contrast between thriving middle classes and masses driven to emigrate or remain and face a life of poverty and destitution while thousands would remain institutionalised.

In 1921 there were 11,000 people in workhouses or poor houses and 6,000 children in reformatory or industrial schools, which remained open until the publication of the Kennedy report in 1970 initiated a slow procedure of closures (Kilcommons et al 2005). An estimated 30,000 women had passed through the Magdalene laundries which closed their last door in 1996 (Finnegan 2001). Thousands of these people, mostly children at the time, were mentally, physically and sexually abused by the church and institutions of the state. It is probable we will never know how many people died or were murdered in these circumstances, but one factor that has come to light recently is the complicity of the gardaí with these crimes. The 2005 Ferns Report on the findings of an inquiry into allegations of clerical sexual abuse revealed that complaints of sexual abuse at the hands of the clergy made to the gardaí as recently as 1988 did not appear to have been recorded in any garda file and were not investigated in an appropriate manner. The results of the Murphy report, issued in 2009, drawing on numerous public inquiries into clerical child sexual abuse, reported on the collusion between senior gardaí and the church in covering up the allegations of abuse while the gardaí had been issued the task of investigating the matter.

“A number of very senior members of the Gardaí, including the Commissioner in 1960, clearly regarded priests as being outside their remit.” (Murphy Report 2009)

The decades that followed the pacification of the Free State, from the nineteen thirties to the late sixties are considered a time of ‘low crime’ in Irish society (Mulcahy 2007) but who has the power to define what is a crime? The gardaí and indeed the state clearly viewed the church as being above the law. Deference to authority displayed in Irish community life enabled the continuation of system of abuse and exploitation that destroyed thousands upon thousands of lives.

Perpetual State of Emergency

While integration between the police and the public had gradually developed under the Southern state there had been no such image of consent generated for policing in the North, which was divided along sectarian lines between nationalists who contested the legitimacy of the British state and unionists loyal to the crown. The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association took to the streets of Tyrone and Derry in protest at the discrimination of nationalists by the Northern state in 1968, calling for the reform of employment, electoral and housing policy but were faced with hostile unionist groups and attacked by the RUC, who had policed the Northern six counties since partition. The British Army was assigned duty in Belfast and Derry the following year in response to fears that the Irish government was planning a military invasion following a statement by Taoiseach Jack Lynch:

“The Irish government can no longer stand by and see innocent people injured and perhaps killed”.

Civil rights marches continued until January 1972, which were now mobilising against the increased use of internment by the British State, when soldiers opened fire on unarmed civil rights protestors killing 14 people; an event known today as ‘Bloody Sunday’.

These events sparked a resurgence of political violence north and south of the border. The continued contestation of the Irish state by militant republican groups coupled with ambivalent sentiments within Fianna Fáil over ‘the Northern question’, particularly following the ‘arms crisis’ when Fianna Fáil ministers imported weapons to supply to republicans, caused a wave of panic in the government that conflict in the North would spill into the South. The Irish state responded to this threat by heavily investing in powers for the policing of republicanism. The 1939 Offences Against The State Act (OASA) was amended in 1972: section 30 enabled the detention of suspects for 48 hours before charging; section 31 of the Broadcasting Act facilitated state censorship of Sinn Féin and the IRA, preventing republicans from accessing the media; and section 38 provided for the establishment of the juryless Special Criminal Court through which scheduled offences would stand trial. Following heightened armed struggle in the South a state of emergency was declared in 1976, enabling the detention of suspects for up to 7 days, although the state had remained in ‘emergency’ following the 1939 OASA. Since formation the Irish state has functioned within a state of emergency for 51 out of its 90 years (1921-2011).

Gradually over time anti terrorist policing has become normalized as powers enabled through emergency legislation have increasingly been used in response to non paramilitary crime (Vaughan and Kilcommons). The gardaí were effectively given carte blanche to police republicanism by any means necessary and within this context the Special Branch redeveloped.

The Heavy Gang

From the early 70’s a group of Special Branch detectives, skilled in interrogation tactics and extracting confessions by verbal, physical or mental abuse, operated with discretionary powers until a ruling by the Supreme Court in 1979 put pressure on the gardaí to operate within legislation. It was now possible to account for the numbers of individuals taken into custody, and figures revealed a massive disparity between the numbers of individuals arrested under Section 30 of the OASA and those charged. It became clear that the rights and freedoms afforded to citizens of the Irish state were being suspended on a massive scale. Out of 2,308 people arrested under section 30 in 1982, only 256 were charged. In 1984 only 374 were charged out of 4,416 arrested under the same act (Dunne and Kerrigan 1984, Vaughan and Kilcommons).

In the absence of thorough research on state abuses of emergency legislation including the exact number of people wrongfully arrested and interrogated by ‘the heavy gang’ (14) , or falsely prosecuted by the Irish judiciary it is necessary to rely on information from individual cases that came to public knowledge through public campaigns and media investigation to show the human cost of policing by any means necessary.

“We are the special boys. We're experienced at getting confessions. We've handled dozens of murders and know a murderer just by looking at him” (15)

Christy Lynch, a 26-year-old soldier, confessed to the murder of Vera Cooney following a 22 hour interrogation in 1976 and was sentenced to life imprisonment. The only evidence supplied to the trial was Lynch’s confession. On its third appeal in 1979 the case was thrown out by the Supreme Court, which ruled that the behaviour of the gardaí could not be legitimated by upholding the conviction. Lynch has received no compensation from the state for the 3 years he spent in jail and Vera Cooney’s murderer has never been found.

Forty members of the Irish Republican Socialist Party were arrested and interrogated by the gardaí following the Sallins Train Robbery in 1976 (Brennan and Kerrigan 1999). Some of the men signed confessions but stated in court that they had been violently coerced into doing this. They received further beatings following the court case. In denial of the charges gardaí claimed that the men had inflicted the injuries on themselves. Justice Barr adamantly defended the gardaí against claims of abuse declaring that it was unthinkable that they should be accused of conspiring or perjuring themselves and ruled that the men’s statements were made voluntarily (Inglis 2004). Nicky Kelly and five others stood trial at the Special Criminal Court for the theft of £200,000. The case collapsed, but the retrial found three of the men (Breathnach, McNally and Kelly) guilty on the basis of the confessions. Kelly had skipped bail at this point. Breathnach and McNally spent 17 months in jail before being acquitted on appeal. Nicky Kelly returned to Ireland in 1980 believing the charges against him were dropped but was sentenced to 12 years. Continuous public campaigning brought about Kelly’s release two years later.

A sad and troubling case, which continues to ripple through the public imagination, came to light in 1984 exposing the normalisation of the emergency powers of the state and routinisation of the abusive interrogation tactics of the Special Branch in Irish society. On the 14th of April the body of a new-born baby was found washed up on a beach in Cahirciveen, Co Kerry. The baby had been stabbed several times. The murder squad, the official title for the ‘heavy gang’, arrested Joanne Hayes, her mother, aunt, sister and two brothers and within hours they had signed confessions from the family identifying Joanne as the baby’s mother and murderer but medical evidence contradicted these statements as blood tests could prove that the child was not Joanne’s. A Tribunal of Inquiry was launched into the matter (16) but there was no official recognition that the gardaí had forced the Hayes family to confess to a murder that they did not commit. The Cahirciveen case remains unsolved.

Speaking out against the Gardaí

Towards the end of the 1970’s a combination of forces, including public campaigns and solidarity work with victims of police brutality, investigative journalism, international pressure from human rights organisations and dissent within the force, combined to cause a tipping point which partially dislodged the untouchable position of the police in the arrangement of power that had been consolidated over the previous four decades. This began in 1977 when a large number of confessions were retracted in court by individuals claiming they had been forced under abusive circumstances. Amnesty International followed these brave acts with a report that year stating that they were concerned over the physical and mental abuse gardaí were inflicting in order to gain confessions and over the complicity of the Irish state, specifically the judiciary, in supporting this behaviour. The same year the Irish Times ran a series of investigative articles on the operation of a ‘heavy gang’ of special branch detectives brutalising people in custody. It was later revealed that during this time a number of politicians were approached by two concerned gardaí who reported that confessions were indeed being forced through violence and that gardaí involved were willing to perjure themselves in court to support these confessions (17).

In 1978 the government appointed O’Briain commission recommended 22 measures (18) to be taken to safeguard against abuse of individuals in custody. These were ignored. Setting up an inquiry was enough to give the image of accountability shielding the gardaí from criticism. “Public support for the gardaí was so widespread and strong, compared with that for subversives, that the government was able to defuse the situation by the appointment of an inquiry into the treatment of persons in garda custody” (Walsh 1999).

Local and national solidarity with Nicky Kelly and Joanne Hayes through sustained protests, campaigning and media work kept these cases in the public eye during the early 80s. Following the Kerry Babies Tribunal, the murder squad was officially disbanded in 1984. The Garda Síochána Complaints Board (GSCB) was set up in 1986. 750 complaints had been lodged by 1990. However, public inquiries into garda behaviour had only ever created an illusion of accountability. The GSCB quickly proved that the state would make no serious commitment to holding gardaí accountable for abusive policing. 136 complaints made to the board in 1994 resulted in no prosecutions and only one prosecution was taken the following year out of 154 complaints (19).

A stream of complaints to the GSCB throughout the 90s, originating in Donegal, had not lead to any prosecution or investigation by the start of the new decade, but sustained local campaigning with some support from political representatives compelled the government to act and a Public Tribunal of Inquiry was set up in 2002.

The Morris Reports, published between 2007 and 2008, outlined the results of five major investigations. Two of these concerned a campaign of harassment against the McBrearty family by the gardaí, who attempted to frame Frank McBrearty Senior, his nephew Mark McConnell and son Frank McBrearty Junior for the murder of Richie Barron who was killed in a hit and run in 1996. 12 members of the McBrearty family were taken into custody, interrogated and abused; one individual spent two months in a psychiatric unit after being released from custody (Cunningham 2009). But the McBrearty case seemed only to be a scratch on the surface of police corruption in Donegal as investigations uncovered numerous incidents, outlined in the remaining three reports, in which arms and explosives had been planted on individuals by the guards as a means of enhancing their powers or furthering their careers. Between 1993 and 1994 Superintendent Kevin Lennon (who was fired) and Detective Garda Noel McMahon (resigned), in an attempt to move up the chain of command, fabricated a number of explosives finds. The investigation found Chief Supt Denis Fitzpatrick complicit in the behaviour of these gardaí in framing an innocent individual as an IRA informer. The Tribunal also found that Sergeant John White orchestrated the planting of an explosive device in 1996 at a protest site in Ardara which would enable him to arrest protestors under Section 30 of the OASA. The report revealed that two years later Sergeant White with the help of Detective Garda Thomas Kilcoyne and Sergeant Jack Conaty, Garda Martin Leonard and Garda Patrick Mulligan, had planted a firearm at a Traveller Halting site, enabling him again to act under Section 30.

The findings of the investigation, headed by Justice Morris, exposed systemic and institutionalised corruption and abuse of power throughout the force, ranging from low ranking officers to senior level, and have resulted in a series of resignations and recommendations for reform. Justice Morris listed the systemic flaws institutionalised within Irish policing as a promotions system that was problematic and not transparent, no accountability structures and no apparent disciplinary mechanisms while broader failures enabling corrupt and brutal policing were rooted in the absence of democratic accountability. No police commissioner or politician has been called to question for the cases mentioned here. This tribunal stands as the first investigation into the behaviour of the gardaí that has taken a critical view of the force, but a Tribunal of Inquiry merely investigates cases and publishes findings and has no power to create real changes within the police force or the state.

“There is nothing between us and the dark night of terrorism but that Force. While people in this House and people in the media may have freedom to criticise, the Government of the day should not criticise the Garda Síochána." (20)

The Irish police emerged out of a colonial, military model assigned the task of administering state sanctioned terror and violence, specialising in counter insurgency operations, extra judicial imprisonment and executions. Yet public consent for this force was easily won through association with the values of an imagined national culture and the guard took position in community life, along with the parish priest and school teacher in the ‘blessed trinity of communal control’(Vaughan and Kilcommons). Until recently conflict in Northern Ireland has deflected criticism from the force and has legitimated a police system that relies on emergency legislation and unaccountable powers. The stories in this collection are shaped by such a history.

For ease of reading you can download a PDF of the entire text in A4 format or fold over A5 format.

Return to the index page of Make Policing History

Leave us a comment or share your experiences

6. Cumann na nGaedheal, a conservative party who kept a policy focus on free trade and law and order acting in the interests of the middle classes, remained in power until the electoral success of Fianna Fáil in 1932. They then merged with the fascist “Blueshirts” in 1933 to form Fine Gael.

7. The first “Special Branch”, officers specifically assigned the task of counter insurgency policing (intelligence work, surveillance, infiltration) formed under the London Metropolitan Police in 1883 to monitor the international underground republican movement, specifically the Irish Republic Brotherhood.

8. Internment; imprisonment without trial or formal charge, was a key practice in pacifying the state north and south of the border

9. The DMP had viciously attacked striking workers during the 1913 lockout, killing two and injuring hundreds in an effort to smash attempts to unionise and had operated side by side with the British Army during the 1916 Easter Rising.

10. The Northern section of the RIC was renamed the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) in 1922 and recruited a large number of ex RIC officers from the South.

11. Garda Commissioner Michael Staines quoted in Mulcahy and Shapland 2008.

12. Mac Gréils 1996 study, Prejudice and Tolerance in Ireland, found that a majority of survey respondents would prefer to have a guard as a neighbour above any other professional.

13. The Blueshirts or National Guard were a right wing political organisation inspired by fascist, anti communist trends in Europe. See http://www.lookleftonline.org/2010/08/fine-gaels-fascist-roots/

14. The name given to detectives specialising in gaining confessions, usually through violent means.

15. Detective Inspector John Courtney to Christy Lynch during interrogation (Sunday Tribune 05/08/07).

16. The tribunal, headed by Justice Lynch, discovered that Joanne had given birth to a child that had died shortly after, that the child’s body had been buried at the Hayes family home in Abbeydorney, Co. Kerry and that Joanne had told this to detectives during interrogation. Although medical evidence could show that the Abbeydorney baby had died of natural causes, Justice Lynch ruled that Joanne had murdered her baby. He also argued that although the Hayes family hadn’t actually taken the trip to Kerry to dispose of the body they had planned to and when questioned had become so overwhelmed with guilt over their grim intentions that they had confessed to the murder of the Cahirciveen baby. The final report of the tribunal was widely discredited and disbelieved.

17. See All in a life: Garret Fitzgerald, An Autobiography, 1991

18. The 1978 O’Briain report identified emergency powers enabling the detention of suspects in custody for 2-7 days as problematic. Among the recommendations the report advised that the discretional practice of holding individuals in police stations outside legislation should end, that arrestees should have custodial guardians and that interrogation rooms should be equipped with recording equipment.

19. It has taken consistent pressure from international human rights bodies (Committee for the Prevention of Torture and European Court of Human Rights) to get the Irish state to reluctantly admit that a complaints board that ultimately functions as gardaí investigating complaints against their colleagues was not impartial nor ever likely to achieve democratic accountability. The board was dissolved in 2007 and replaced by the Garda Síochána Ombudsman Commission.

20. Fine Gael Minister for Justice Michael Noonan responding to criticisms of the gardaí on the 10th November 1987.

Working-class experiences of the Gardaí

A current crisis - Today we live in a media-saturated society that sensationalises crime and gangland warfare in working-class communities. Some say the media through its various functions has become a sort of moral barometer for the national imagination in terms of how the working classes are perceived. This, perhaps, is done through newspapers' slash headlines like “Thugs never had it so good” or “Bugsy Malone gang terrorise North Dublin”, or through current TV shows that give a picture of working-class people as rough and disrespectable such as Jerry Springer or The Royle Family. All this actively contributes to the respresentation of the working classes as disresputable.

Media moralisation of the working classes serves to cast shadows over the real circumstances people face on a daily basis and, in particular, the situations and realities working-class people challenge in their communities. Not only do they suffer from intergenerational unemployment, poverty and bad infrastructure; working-class people also dealing with and recover from the impact of drugs and drug dealing.

On an almost daily basis, debates arise at the difficult intersections where communities experience how these problems are policed. One the one hand, people depend on garda protection and on the other hand, gardaí at times abuse their power either though physical brutality or using intimidating tactics or indeed both. This is embedded within some working-class communities and it is particular to the experiences of young working-class males. The big question that arises from this is what if part of the current crisis experienced in our communities today is actually due to just not knowing enough about people and their situations, like a lack of knowledge about how it is for those living in such crisis but not having the opportunity to have their voices and experiences heard?

When I began thinking about this, the one thing I knew for sure was there was a lack of connection to the truths in individual lives. Not a lot of opportunity is given to working-class males to voice their experiences, in particular their experiences of the gardaí. This is especially because there is such negative media representation blocking any chance of them telling their side of the story (as they say themselves). There is so much hidden about working-class life and cultural resistance. So much is hidden about people’s lives behind the splashy headlines. Working-class culture is rarely documented for purposes other than to entertain or to sell popular culture. Rarely is the knowledge of working-class youths sought for the purpose of consciousness raising and healing.

This small piece of writing comes from my discussions with working–class youths in a council estate. The estate itself is rather isolated from the larger surrounding community and local elites frown on the area and openly refer to other housing estates as "decent places". I must note here that the same elites refer to the local Garda station as the "Barracks". All the discussions brought forward here come from working-class self-organised community education.

Guilty until proven innocent

It is well known that the working classes view the police with suspicion: one would wonder why! Writers on social class such as Richard Hoggart tell us that working-class people see the police as being against them, or out to get them, rather than working on their behalf. It is well accepted at a local level that gardaí view young working-class males with suspicion. The lads I work with will openly say,

“When you are working-class, you are guilty until proven innocent”.

The lads tell of old sayings regarding the gardaí’s suspicion of them. These sayings are not only from their contemporary experiences with the gardaí but also come from what they heard their parents say. I have termed these “generational hearsays”. Sayings such as,

“We are aliens of the state” or “it’s a long road without a turn, the guards have long memories”

might not seem important at first but when you look at them in the context of coming from marginalised youths that have in various different ways become known to the gardaí (so to speak) then they begin to paint a different picture. One that might say that perhaps they have been marginalised by the state since they were born and that the gardaí are always watching them and remembering from one generation to the next.

Caught in the middle: working-class youths and power networks

There was always a great willingness in the group to speak about their experiences and in particular their experiences of the gardaí when they were in their early teens and growing up in the community. These experiences and same old Garda tactics carried into their adult lives. All spoke about the feelings they had about being treated differently. For instance, the family name and any past offences the family had whether it was a father or an older sibling would be dragged up in conversations by some gardaí:

“The dirt was always dragged up for us, like thrown in your face”

The garda would say

“Ah it’s you, young such and such, sure we know your father well”

Participants said

“We would hate the garda for this; it was the worst thing ever”

In any discussions around this the lads went on to say,

“It’s like this - it’s always about where you come from, like a council estate and all that, it’s never about me and how I am now, it’s always about the past and what I’ve done or what has happened in your family. This is always carried on, and even when you do go before the courts now as an adult the garda will give all the past. For example, I’m off drugs three years now and I’m doing a FETAC course. I had a minor traffic offence and was in court recently. The same old stuff was brought up. ‘Well your honour, this man has previous drug convictions; he’s from a disadvantaged neighbourhood’ etc. It’s never about how I’m doing now or what changes I’ve made in my life, the judge sometimes knows when the gardaí are using intimidation tactics, and have often cut across the garda and said ‘well garda, that’s in the past, it’s how this young man is now and what he’s doing with his life now concerns me’ ”.

Caught in the middle - being netted

When the subject of power was brought up in discussion, the lads would say everything to do with gardaí, being working-class and living in a council estate is all about power networks. The gardaí have the power and know exactly how to use it in certain situations. The lads spoke about the “net” or being “netted” and this is, the lads explained, one of the gardaí’s strongest tactics and one that can result in dangerous consequences for working-class youths.

“It’s like this, in council estates there is nothing much to do, so you’re more vulnerable to what we call getting netted in by drug gangs and the guards. The thing is this. Gangs pick on young lads they know - or if they have known family members. Some lads I know have got involved, simply because they were asked as a favour to mind a stash, the gangs do this. When this happens it’s hard to move away, even if you never take drugs, because now you are seen to know too much about the gang. Most lads take drugs and when the guards move in on them, like when they are caught with whatever drugs they have on them, even if it’s only small and enough for one’s own use, the guards will use this to bargain with you for information on the bigger gang members. If you do, they let you off with your offence but they still have you. Now you’re a tooth for the guards and they use it all the more especially to intimidate lads around gangs. This is known as the net because now you are either what’s known as a ‘tooth’ (a tell tale) for the guards, or seen to be true to the gang, both situations are bad; there is no real middle ground in this. It’s fear both ways”.

The lads in the group spoke repeatedly about how there was no real middle ground in this situation and how this is the ground or the intersection of community policing where the gardaí really abused their power.

“It works this way, if a garda sees you talking to a group of lads he might stop the car and shout at you ‘hey crack head, call up and see us again, like you did last week for a chat’. This is all they have to say, the only saviour is that the lads you’re with know what the Guards are like and know their tactics because it’s been done to them”.

Something rotten in the gardaí

A Dublin community activist who knows about the hidden aspects of working-class youths’ experiences with the gardaí had this to say recently:

“Towards the end of 2007, a young man, aged nineteen, from a deprived neighbourhood came to tell me that on the previous day he had been taken to a Garda Station for a drugs search, during the course of which he had been assaulted by several gardaí. When no drugs were found on him, he was told to leave. He claimed that as he was leaving he was shoved forcefully towards the door by a garda, which caused his head to smash the glass panel of the door. He said that he was then brought back into the Garda Station and charged with assaulting the garda and causing criminal damage to the door”.

In discussions around bad police behaviour the lads agreed that there is something rotten at work in the police. They spoke of how subtle Garda brutality can be, they told various stories but one that stuck in my mind was this one,

“I was playing football on the green with a couple of the lads. We decided to get our own team together. Tony [not his real name] had been in trouble for shoplifting; he robbed a roll and milk in Tesco’s and then some bottles in the off-licence. He was due up in court in the coming weeks. Anyway, the game was going good and the Garda car pulled up. The guards got out and started playing football. They nearly broke Tony’s ankles, the kicks they were giving him. There were four of them, they were getting the digs in wherever they could, and saying "the courts might let you away with it, but we won’t”. Then eventually they just went away and left Tony on the ground in agony. They do that and they know where to bash you too so it does not leave bruises, but with Tony they didn’t care. They knew he wouldn’t say anything to anyone.”

Another issue that come up in discussion was the shooting of a youth in an ATM robbery. The comments here were on how the papers praised the gardaí’s actions,

“We know he was in the wrong but there was no need to kill him, no one knew anything about him. He was alright he was, he just got desperate, he just became disposable. The papers were full of back slapping for the brave guards involved. Do you know what the papers said? They said “This was a brave and successful bit of work by our force”.

Again a community activist speaks out on police behaviour towards working-class youths,

“There’s an old dominant value system at work in Ireland. All the old gardaí have it, it’s a sort of 'live up to standards’ which the police force work out of. Because there is this dominant idiom to live up to, young gardaí starting out in the force cannot afford to be seen to sympathise with working-class youths, in particular those who are marginalised or drug users; it’s just not done. To combat this, or rather as I see it, there is a role of “macho garda” played out among new recruits in the police force. This means the less you are seen to sympathise and the more you are seen to be nasty, intolerant and such towards the scumbags as they call them, the more accepted they are in the force. So yeah, there are some nasty ones about who work out of that value system, sure the lads will tell you themselves they are treated like dirt, especially in A & E (accident and emergency) and the police stations as we all know.”

Garda relocation: behind closed doors - it’s like this

In group sessions some of the lads spoke out about how just silly street corner fooling around could result in more serious consequences. They explained,

“We were drinking some cans one night and the guards came along and were slagging us off - saying things like ‘Ah there ye are, the same auld suspects knacker drinking as usual, would the pubs not have you lads’. Some of us said ‘ah go way you’re only guards, sure what can ye do about it, sure you’re all uniform and mouth’. We were hit across the face with batons and kept in the cell for the night. The guards were saying to us about how we had triggered the short fuse of the garda. They were explaining the actions of one particular garda who was a bit heavy handed on the baton. They were saying ‘you above all lads know what it’s like to just lose it, he just lost it lads, you have driven him to it, he is a good man but he’ll take no nonsense, he has a job to do’.

“My friend’s nose was broken he was fifteen years old and when his parents came to get him they were complaining and asking how he was in such a state. The guards were saying ‘drunk and disorderly but we will let him off this time’. The fact that my friend was drinking and that the garda were willing to overlook it made his parents delighted to have the situation cleared up. The garda in question was relocated to a different district that same week”.

The lads spoke about how gardaí are relocated to different places especially those who are considered to have a short fuse or those who are capable of just losing it,

“It goes on all the time and it just gets forgotten about, it’s like out of sight out of mind and anyway sometimes it’s just best to say nothing at all about it. You would just be bringing the whole thing up again and the guards can make that be a nightmare for you”.

In our discussions about their experiences with the gardaí there was strong emphasis placed on making sure I documented their experiences as a reality in our current times and not as they said themselves,

“Like something that is shown on the TV, like in a documentary where the police have someone in custody and it shows all the rights they have, like the way they can ask for stuff like drinks, smokes, or phone calls or the American way, like it shows all the time in films. Where the person is arrested and being questioned, it shows them saying things like ‘I will wait till my lawyer gets here’ or ‘not without my legal adviser’. Well that’s not how it is in the real world, here the gardaí just laugh at you”.

They went on to tell me that the best thing to do when in the situation of arrest is to just say “no comment” or “I’m not signing anything”. They went on to say that the gardaí still have the power no matter what, especially if you’re drug dependent and you are taken into custody or held overnight,

“If you’re drug dependent you could be left in a cell for up to sixteen hours. You would be climbing the walls. I was on prescribed drugs at the time I was arrested and was just left there. The guards know they have you now, you have a right to call a doctor but they leave you till you’re on your knees. Even then there is no guarantee you will get a doctor, it all depends on who’s around and if a garda thinks you might be a good source of information for them. The guards have the power here and offer drugs sometimes, or the stash you had on you when you were arrested can be on offer to you either. It depends on how desperate you are and the guards play you on this. I tell you it’s a vicious circle”.

Working-class resentment of Garda harassment:

it’s the gardaí that create the trouble

Local women in the community have spoken of how the gardaí are something like a militia,

“We understand it’s their job to patrol the area, but it’s a bit ridiculous when you see them hanging around all the time. They do hassle the kids in the neighbourhood. What happens is this, the guards hang around when there’s no need. This only causes tension and a fear in some of the parents that some of the lads are going to strike out at them, like throw a bottle or stone at the car. We try to tell them don’t let them get to you. But they don’t always listen, they are too mad at them”.