Over 30 years of anarchist writing from Ireland listed under hundreds of topics

Routes to freedom - the platform, its shortcomings and the WSM practise - does it remain relevant?

One of the key foundation documents for the Workers Solidarity Movement is the ‘Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists (Draft)’ This text was written in Paris in 1926 by a group that included exiled Russian and Ukrainian anarchists and was very influenced by the lessons they drew from the Russian Revolution. Three of the authors -- Nestor Makhno, Ida Mett, Piotr Archinov -- were then and now very well known anarchists, the remaining two -- Valevsky and Linsky -- I know relatively little about.

One of the key foundation documents for the Workers Solidarity Movement is the ‘Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists (Draft)’ This text was written in Paris in 1926 by a group that included exiled Russian and Ukrainian anarchists and was very influenced by the lessons they drew from the Russian Revolution. Three of the authors -- Nestor Makhno, Ida Mett, Piotr Archinov -- were then and now very well known anarchists, the remaining two -- Valevsky and Linsky -- I know relatively little about.

In this article I intend to examine whether this text has any relevance to anarchist organising today, some 90 years after it was drafted. In addition, what can we say about its shortcomings? Finally, I will look at some of the confusion the WSM ran into when trying to follow it.

The specific context of asking these questions is that of rebuilding one of the longest running platformist organisations, the WSM. The WSM only just survived the years of the crisis because of our failure to discover a revolutionary alternative to austerity capable of convincing any significant section of the masses that the risk of a revolutionary rupture was worthwhile. It’s only a small exaggeration to say almost 25 years of careful preparation crumbled under the pressure of a couple of years of real but very contained struggle. In such circumstances, it is tempting to simply ditch the past and start the process anew -- all the more so when faced with a foundational document that is anything but complete and also quite dated.

This piece you are reading began its life as the lead in for a Dublin WSM branch discussion this July on whether ‘The Platform’ remained relevant and, in places, draws on our experience of being a self-described Platformist group. My reflections on this suggest that we perhaps did not spend enough time working out a collective understanding of what implementation of the organisational principles of the platform meant.

The appeal of the ‘Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists (Draft)’ to many anarchists today is found in its opening segment:

“Anarchists!

Despite the force and unquestionably positive character of anarchist ideas, despite the clarity and completeness of anarchist positions with regard to the social revolution, and despite the heroism and countless sacrifices of anarchists in the struggle for Anarchist Communism, it is very telling that in spite of all this, the anarchist movement has always remained weak and has most often featured in the history of working-class struggles, not as a determining factor, but rather as a fringe phenomenon.

This contrast between the positive substance and incontestable validity of anarchist ideas and the miserable state of the anarchist movement can be explained by a number of factors, the chief one being the absence in the anarchist world of organizational principles and organizational relations.

In every country the anarchist movement is represented by local organizations with contradictory theory and tactics with no forward planning or continuity in their work. They usually fold after a time, leaving little or no trace.”

These opening paragraphs of the Platform still speak to the experience of many anarchists today, even though they were written almost 90 years ago in 1926.

The Platform speaks to anarchists who have gone through informal organisation and seen that it can’t be a complete answer to the question of how do anarchist build a libertarian revolution and, in many cases, is not even a satisfactory partial answer. The WSM 1989 republication of the text along with our practise of the ideas it contained had considerable international influence in the Anglo sphere and, because English is widely understood as a second language, beyond even that. In the mid 2000’s this influence allowed us to spearhead an international regrouping of anarchism around Anarkismo.net, an international initiative of similar organisations that peaked with about 31 participating organisations in 26 or so countries. By then, the WSM also had about 65 members on paper and even though the number of active members was smaller, we were close to catching the other two significant organisations of the radical far left that existed in Ireland.

The Platform describes in broad terms what WSM tried to build in the 1990s and 2000s:

“We have vital need of an organization which, having attracted most of the participants in the anarchist movement, would establish a common tactical and political line for anarchism and thereby serve as a guide for the whole movement.”

“The only approach which can lead to a solution of the general organizational problem is, as we see it, the recruitment of anarchism’s active militants on the basis of specific theoretic, tactical and organizational positions, which is to say on the basis of a more or less perfected, homogeneous programme”

The WSM implementation

What this meant in practise for WSM was the development of detailed position papers through twice yearly conferences, our magazines Red & Black Revolution and later Irish Anarchist Review, and ongoing public lectures. Through these vehicles, our politics were debated, challenged, modified, and ultimately put down on paper. It was a process on which we must have collectively spent tens of thousands of hours. This informed a very much more substantial - in terms of time - practise of involvement in a wide range of struggles and organisations. And the lessons of that practise were in turn debated and recorded to be built on.

When the WSM went into crisis, at the same time and in part due to, the economic crisis reality started to diverge from what was expected from our positions. It became clear that our investment in political development didn’t guarantee organisational relevance or even the expected level of internal coherence. The sheer volume of some positions (in most cases developed a long time before most members had joined) could sometimes be a dead weight when identifying and taking action relevant to the immediate circumstances. A negative tendency developed among some long term members, where an abstract adherence to the platform was used to try and polarise the organisation along the test of adherence to a never defined ‘platformist’ orthodoxy. And on the other hand another segment of members departed to later become social democrats around their sense that the platform had not, in the end, answered the organisational problems of anarchism.

This was one weakness of the approach the platform encouraged. Another was what it failed to cover. There is no discussion of racism, sexism or other oppressions in the Platform. The excuse is offered that it is a document of its time but it’s still a curious oversight given that the authors’ own experiences included struggles in those spheres. In any case this does make its use as a foundational document problematic as that tends to encourage a tendency to see these struggles as secondary or less fundamental.

For the WSM that manifested in a relatively weak understanding of debates within anti-oppression movements as we sought collective guidance almost exclusively from the relatively impoverished historical practice of the Irish left and the European anarchist movement, the highpoint of which was perhaps Mujeres Libres during the Spanish revolution. On the one hand a lot of our practise for considerable periods was around anti-racist and pro-choice campaigning but the theoretical base of that practise was drawn from the increasingly distant peak of anarchism in the 1910s to 30s.

Post 2013 as WSM tried to understand how to create a revolutionary organisation in the networked age we didn’t break with the platform but rather started to elaborate the areas it failed to cover. Principally this was the question of how class politics intersected with anti-racism, feminism, LGBT/Queer struggles and anti-colonialism. Not just on the macro level of society but how these impacted on anarchist organisation in general and the WSM in particular. We also radically redrafted our ‘Role of An Anarchist Organisation’ position paper to reflect the new organisational challenges of the new period we found ourselves in. Did these changes, which were quite fundamental, mean we have broken with Platformism?

I’m going to try and answer that by returning to the text:

GENERAL PART

I. Class struggle, its role and its value

“In social terms, the whole of human history represents a continuous chain of struggles waged by the working masses in pursuit of their rights, freedom and a better life. At all times throughout the history of human societies, this class struggle has been the principal factor determining the form and structure of those societies.”

In broad terms this claim remains key to our understanding of the world even if we’d perhaps be less inclined to try to use class struggle to explain the Norman conquest of Ireland (for instance).

II. The necessity of violent social revolution

“the structure of present society automatically keeps the working masses in a state of ignorance and mental stagnation; it forcibly prevents their education and enlightenment so that they will be easier to control.”

This feels very dated as it doesn’t really describe how social control works under a modern capitalism that increasingly requires a highly educated workforce with significant amount of autonomy. In 1926 work was still overwhelmingly manual in nature and at the peak of the factory system often quite deskilled. Anything beyond basic education was reserved for the elite and a narrow section of clerical workers. Popular education was a central part of the anarchist movement in many countries as it was the only access to education for large swathes of the working class.

Modern capitalism with its need for educated workers uses much more sophisticated control mechanisms. For instance, it has seen the growth of enormous entertainment industries that can occupy our brains outside of work in a way that doesn’t tend to produce collective organisation or effort. Instead, such entertainment not only provides profit and distraction but even promotes division, competition and meaningless inter group rivalry around everything from X-Factor to Premier football. One of the big success stories for modern capitalism has been to largely succeed in turning the limited threat posed by electoralism into harmless rival identifications accompanied by a commentary that places form so far ahead of content that the system is shocked whenever a vaguely principled politician or party briefly escapes the mould.

The wording here is also overly insurrectionary in emphasis to our ears insisting “there is no other way to achieve a transformation of capitalist society into a society of free workers except through violent social revolution."

The Platform was of course coming from the experience of the Russian Revolution, but even in 1917 in the countryside and a lesser extent the cities that insurrectionary side of that that revolution was as much about defending land and factories that had already been occupied as an attack in order to create the conditions for such occupation. That distinction is important today in areas of the world where the masses are not in desperate conditions and thus really would have something to lose in the destruction that would accompany the failure of a violent revolution.

III. Anarchism and Anarchist Communism

Possibly my favourite line in the Platform remains;

“Anarchism's outstanding thinkers - Bakunin, Kropotkin, and others - did not invent the idea of anarchism, but, having discovered it among the masses, merely helped develop and propagate it through the power of their thought and knowledge.”

This stands in sharp contrast with most of the left which presents socialist theory as coming from the heads of intellectuals to then be implemented by the masses. Failure is often then excused as poor or incorrect implementation of that theory by the masses. In practise this means a strong tendency by many left organisations to approach involvement in struggles as a question of how to most effectively impose the party line on the struggle. Which will often be through seizing control of the decision making mechanisms or more cynically prevent them coming into being in the first place.

The Platform is distinctly communist in terms of the economy it proposes;

“This basis is common ownership in the form of the socialization of all of the means and instruments of production (industry, transport, land, raw materials, etc.) and the construction of national economic agencies on the basis of equality and the self-management of the working classes.

…

It is from this principle of the equal worth and equal rights of every individual, and also the fact that the value of the labour supplied by each individual person cannot be measured or established, that the underlying economic, social and juridical principle of Anarchist Communism follows: "From each according to their ability, to each according to their needs".

V. The negation of the state and authority

On the question of electoralism the platform describes quite well the limits exposed one more in the recent Syriza experience in Greece, that is;

“The conquest of power by the social democratic parties through parliamentary methods in the framework of the present system will not further the emancipation of labour one little bit for the simple reason that real power, and thus real authority, will remain with the bourgeoisie, which has full control of the country's economy and politics.”

The major difference being that in 1926 the domination of small economies by large economies was still mostly through imperial conquest, occupation and direct colonialism. Today these are the imperialist methods of last resort. Methods that only normally come into play when the international mechanism of capitalist globalisation are inadequate or are opposed. There was no need for Germany or France to invade Greece to assert their economic interests as the ECB and IMF acting through the Euro proved well able to bring Syriza to heel. The bourgeoisie who turned out to have full control of the Greek economy were only partially Greek in composition. As an aside this also returns us to one of the weaknesses of the Platform, the failure to address colonialism even if in practise the later ‘platformists’ have generally had amongst the best class struggle anarchist approaches to that question.

There is one point on which the platform touches on the question of relative privilege among the working class, broadly defined. This question has become one of the sharp dividing lines within the left today, what has the platform to say;

VI. The masses and the anarchists: the role of each in the social struggle and the social revolution

“The principal forces of social revolution are the urban working class, the peasantry and, partly, the working intelligentsia.

.. the working intelligentsia is comparatively more stratified than the workers and the peasants, thanks to the economic privileges which the bourgeoisie awards to certain of its members. That is why, in the early days of the social revolution, only the less well-off strata of the intelligentsia will take an active part in the revolution”

This brief mention of an understanding of relative privilege as a significant organisational question is a starting point in overcoming the lack of any other mention of how relative privilege and marginalisation play out in movements. It leaves the door open to the suggestion that the authors would not have ruled out a broader use of such understandings. As did their practise of autonomous Jewish military units and communes during the revolution in the Ukraine as a way of addressing the often murderous additional oppression of the Jewish population.

But the other aspect of this paragraph is the relatively simply stratification it presents where apart from the more complex ‘working intelligentsia’ there are only peasants and urban (presumably factory) workers. Did that really describe the global masses of their time or even the situation in Europe? It certainly isn’t a complete summary today, even before we reflect the huge relative increase in the ‘working intelligentsia’ category as the percentage of peasants has radically reduced and factory workers has reduced and geographically relocated considerably.

This isn’t nitpicking. On the organisational, strategic and tactical levels an understanding of the composition of society and the stratification of the masses is a central determining force that would need to be returned to again and again. The very simple class classification system outlined in the platform is only useful for the simplest of polemics. It is not a tool for building an understanding that can overcome the divisions created and maintained by the stratifications. Class unity cannot be brought into being through asserting it to already be the case, regardless of the divisions that exist. It has to be built in struggle, struggle that has overcoming division as a primary focus in order to avoid the dead end of creating relatively privileged and powerful fragments of the class around skilled (white, straight, cis-male, citizen, etc ) workers.

But returning to the question of organisation the following two sections again describe the intended practice of the WSM in terms of mass work;

“In the pre-revolutionary period, the basic task of the General Anarchist Union is to prepare the workers and peasants for the social revolution.”

“The anarchist education of the masses must be conducted in the spirit of class intransigence, anti-democratism and anti-statism and in the spirit of the ideals of Anarchist Communism, but education alone is not enough. A degree of anarchist organization of the masses is also required. If this is to be accomplished, we have to operate along two lines: on the one hand, by the selection and grouping of revolutionary worker and peasant forces on the basis of anarchist theory (explicitly anarchist organizations) and on the other, on the level of grouping revolutionary workers and peasants on the basis of production and consumption (revolutionary workers' and peasants' production organizations, free workers' and peasants' cooperatives, etc.).”

Anti-electoralism would be a better term for us to use than the confusing anti-democratism but otherwise and taking into account the shortcomings already highlighted this sketch remains valid. What is an interesting question for the modern Platformist movement is the relatively central focus on radical co-ops and the role they would have to play when we imagine a revolution that is not simply insurrectionary in construction. That is in terms of what we are to build in the shell of the old society that then makes a defensive revolution a reasonable proposal to working masses who often are not desperate or on the edge of starvation.

Constructive Part

This seems the most distant today because it talks of how to organise a post revolutionary society in terms that are broad but still based on the societies of the 1920’s when the peasantry made up most of the population of most countries. But the general identification of the three key areas is worth picking out as remaining relevant;

The three essential immediate tasks of the revolution are identified as

“To find an anarchist solution to the problem of the country's (industrial) production.

To resolve the agrarian question in the same manner.

To resolve the problem of consumption (food supplies).”

Again we see a more sophisticated understanding what what is need than the initial focus only on “violent social revolution”;

“Essentially, the revolution's mightiest defence is the successful resolution of the challenges facing it: the problems of production and consumption, and the land question. Once these matters have been correctly resolved, no counter-revolutionary force will be able to change or shake the workers’ free society. However, the workers will nonetheless have to face a bitter struggle against the enemies of the revolution in order to defend its physical existence.”

Revolution here is presented more as the process of solving the problems of a new (and communist) society. The armed revolutionary aspect is a necessity imposed by the need to defend that society rather than the suggested mechanism for reaching it.

The final area I want to touch on is the organisational section because once again this essentially sketches out the general WSM approach. However I want to be critical of how we understood it and particularly our tendency to collapse the four principles it outlined together without understanding what separated them from each other.

ORGANIZATIONAL PART

“The platform’s task is to assemble all of the healthy elements of the anarchist movement into a single active and continually operating organization, the General Union of Anarchists. All of anarchism's active militants must direct their resources into the creation of this organization.”

This sentence is probably among the most contested of the document, including quite often within WSM. The Platformist approach is sometimes misrepresented as being about just grouping together the best militants. That is grouping together a relatively small number from within the anarchist movement that will influence the movement in general through the power of their ideas. Elsewhere on the left and occasionally within Platformism that sort of ‘best militants’ grouping is sometimes called a cadre organisation. Cadre is a military term about the methodology of maintaining a small but highly trained force in peacetime that forms the officer layers of a very much bigger conscript army when war arrives.

Instead of war we are talking here about revolution. Those who in effect advocate a cadre organisation hold to the idea that this side of the revolution the revolutionary organisation can only group together a tiny minority and that this means the quality of that minority is all that is really important. I say ‘in effect’ because the obvious contradiction between the cadre form and anarchism has meant you have anarchists who advocate the form but oppose the use of the term cadre. Which introduces contradictions that prove damaging in the medium term as the form is adopted in a way that makes critique of it more difficult. You end up with a ‘that’s not what we are’ denial that then necessitates one of those frustrating debates about what words really mean.

In any case the language used in the Platform above is quite different, it excludes the cadre approach. It aims to group not the best anarchists but (almost) all anarchists. The solution advocated is not the identification and recruitment of a knowledgeable and skilled cadre but rather a methodology to bring together most anarchists in a manner that collectively generates and allows implementation of the best solutions they reach. Platformist groups that have ‘gone bad’ have been those groups that confused the first process for the second.

To repeat, the Platform argues for grouping together “all of anarchisms active militants” - the only anarchists it excludes are the implicit ‘unhealthy elements.’

However, unlike the Synthesis counterproposal, the Platform doesn’t want to group all anarchists together ignoring political differences but rather insists that the major function of the grouping together of militants is to discuss and resolve those differences in a collective fashion and then implement what is agreed.

The question of unity

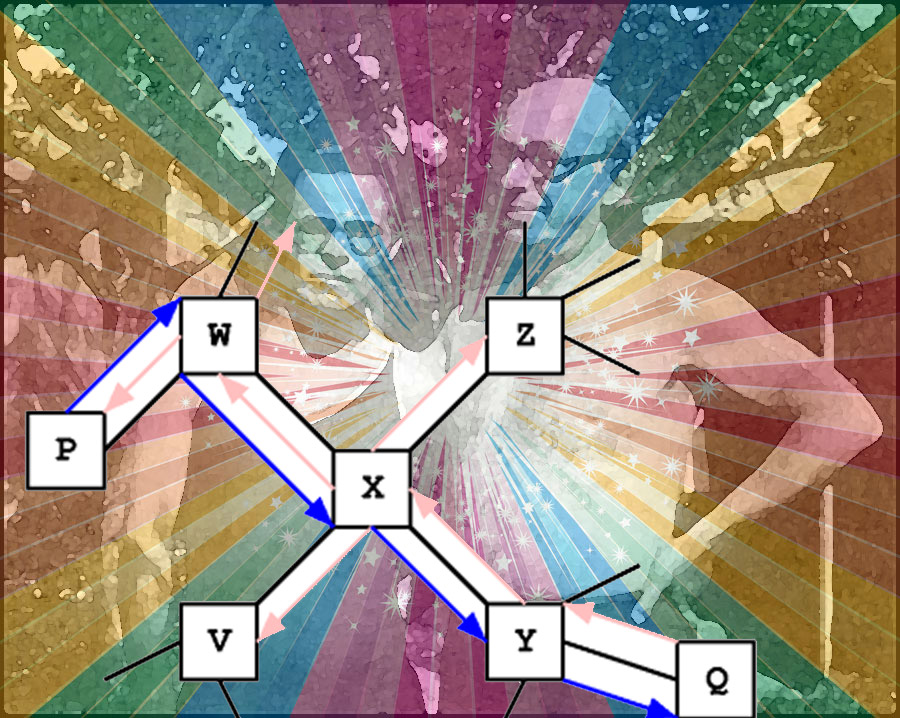

As the text continues it defines the four key organisational principles through which this is to be achieved;

1. Unity of theory

2. Unity of tactics or the collective method of action

3. Collective responsibility

4. Federalism

“Federalism means the free agreement of individuals and entire organizations upon collective endeavour, in order to achieve a common objective.”

The WSM had a strong focus on the first point, unity of theory, through the development and repeated modification of position papers. For the most part this worked at preserving a collective baseline that could be referenced in new situations but our methodology for generating it left a lot to be desired. We basically copied the methodology of much larger organisations like the unions and the traditional left. Which was one where motions were written by individuals and then debated and voted on by the WSM as a whole at twice yearly national conferences.

The problems here were that

a. the intellectual work of generating large blocks of text only suited a small minority of member. Probably less than 10% of members ever submitted a substantial motion to conference even though dozens of such motions were submitted over 25 years. There was little or no effort prior to 2011 to change that dynamic, in effect accepting the existence of a de facto internal cadre carrying out the most important intellectual work. Some of those who subsequently left not only embraced this but based their analysis of ‘what went wrong’ around the admittance of members they consider to lack sufficient intellectual understanding. A mea culpa here - probably as much as 50% of the text of our motions after 1990 was generated by me, it’s a form of thinking out an issue and codifying the results that comes very easly to me.

b. motions being generated by a small minority resulted in a lot of the members being quite passive with regard to the content of these motions, in particular where the content was not politically controversial. This had the biggest impact in areas of resource allocation as it meant that unless members strongly disagreed with a proposal they would vote for it. But that didn’t indicate a personal commitment to the work required to implement it.

In a certain sense there need not be a problem here. Often there will be tactical proposals that are compatible with other tactics and so the only question really is whether there are enough collective resources that people would allow a particular experiment to go ahead.

The problem arises when there is the expectation that the act of getting a motion passed is enough in itself to then expect all members will work to implement it in circumstances where the act of passing is really more of a ‘sure, give it a go’.

This is in part a discussion around what ‘tactical unity’ should be read to mean. And partly a discussion about understanding that implementing any project will always be a case not just of winning passive agreement but also generating ownership and ‘buy in’. That second factor was seldom understood in WSM, instead people tended to fall back to simply demanding that ‘Unity of tactics’ meant people had to implement their project once it had been voted for.

The challenge of resource allocation

That approach might work if the original decision making process is one in which the entire work of the organisations is weighed up and the votes take place in the context not of deciding whether something is a nice idea but rather on whether resources can be moved from some other area to that area. Obviously this would also have a huge impact on the likelihood of a motion being passed and required a very different decision making mechanism, one outside the tradition of unions and other organisations. It didn’t help that we were an all volunteer organisation while unions have a large staffs of full timers to administer and co-ordinate the allocation of resources. As the organisation becomes bigger the scale of trying to weigh all the demands on resources against new demands in motions become ever more complex. Indeed even at the level of an organisation with 50 members in 3 cities it’s close to impossible for every member to keep track of all the needed information.

Pre 2013 the WSM had no mechanism to weigh up competing demands for resource beyond members including ‘make a priority’ type phrases in their motions. But actually that simply displaced the problem as before long almost everything of importance to anyone was made a priority. In retrospect it seems remarkable that we never recognised that the developing friction that was causing required different methodology or a change in approach to what we meant by tactical unity.

But importantly the second issue here is around the idea that tactical unity should be translated into every member implementing every decision. WSM went through periods where that was attempted, normally in the context of genuine mass popular campaigns that involved a significant minority of the working class. The most recent example of that approach being organising against the Household Tax where there was considerable pressure on every member to make it the main focus of their activity. There was logic to that as at the time it was the biggest struggle in quite some years. But there were also problems beyond the obvious one that it is never a good idea to put all your eggs in the one basket. Those included;

a. Newer members in areas where they were the only member didn’t necessarily have the confidence, experience and skills to deal with the manipulative behaviour of the leninist groups.Most of our newer members who found themselves in this sort of situation quietly drifted out of WSM .

b. The campaign was a very basic class based one with limited economic demands. Making it the major focus of every member would have resulted in members who were active in other areas, in particular anti-oppression struggles having to reduce or temporarily abandon that activity.

c. The Household Tax campaign was eventually defeated in a way that was quite demoralising. With most of our members putting most of their effort into that struggle the result was widespread demoralisation in WSM in the final months that was not balanced by success elsewhere.

The wrong case for tactical unity

It’s often the case that when you argue with Leninists about the need for democracy they fall back on military examples where its only possible for a small number of people to make a decision that has to be made quickly or defeat is certain. Therefore they claim direct / assembly democracy is not essential and should be replaced by the representative forms of democratic centralism. Arguing for general patterns of behaviour based on extreme examples will seldom give good results. Yet platformists tend to do this with relation to tactical unity.

In the conditions of the revolution in the Ukraine you can certainly see why quite a tight tactical unity would be needed. It was important that everyone would implement a particular plan at the same moment in time. ‘We are going to attack that hill at dawn from three sides and we need you to attack the river crossing 5km away 30 minutes before hand as a diversion to draw away reinforcements.’ But as with the Leninists and democracy just because extreme examples exist where a very strict definition of tactical unity needs to be followed this doesn’t then mean that such a level should be the default position in most circumstances.

Instead I’d suggest that tactical unity should not be read as anything more than a requirement to implement the tactics that are agreed if they apply to the given area a member is active in. So in relation to the household tax campaign tactical unity would mean arguing for a boycott of the charge, if that was the work you were involved in, and not a requirement to get involved in that work in order to make that argument. Indeed that must have been the intended meaning of the Platform, why else list Tactical Unity separately from Collective Discipline? There could be times, preferably brief, where the organisation thought that the scale of opportunity that existed did require an exceptional level of tactical unity including an individual requirement for implementation. But that would need to be a clear cut decision rather than, as happened in our case, an assumption some members made and tried to require of others.

Which brings us to Collective Responsibility. This can be read as every individual being responsible for the implementation of every decision but that makes little sense. What makes more sense is if it is understood to operate on both the collective and individual level. On the collective level it is the requirement for the organisation to implement decisions made. If that is to be meaningful it means building into the decision making process a way of weighing up and parcelling out the competition for collective resources. Then on the individual level the implementation of tasks that the individual has taken on should be a requirement, as should the expectation of taking on some minimum volume of tasks. In other words at the individual level the expectation is not that everyone will do X but rather than the individual will take on tasks and implement those tasks as part of a collective process.

When you look at the way the Platform defines the last point, Federalism, we see exactly this expectation in the definition; “the federalist type of anarchist organization, while acknowledging the right of every member of the organization to independence, freedom of opinion, personal initiative and individual liberty, entrusts each member with specific organizational duties, requiring that these be duly performed and that decisions jointly made also be put into effect.”

The conclusion I would come to is that in these core aspects it can be argued that the post 2013 WSM have moved a lot closer to a practical understanding and implementation of the Platform. The pre 2009 WSM had a formal adherence to the Platform but we lacked a practical distinction between tactical unity, collective responsibility and federalism of the sort worked through here. Instead we failed to distinguish between these. And coupled this with an inherited a set of contradictory practises from the unions, left and republicanism that were to some extent in contrast to these points and were administratively unworkable in an anarchist organisation. The end result was that the proclaimed (too intense) unity was seldom realised in practise and this became a source of frustration & friction.

National co-ordination

The platform also addresses head on the tricky question of how you co-ordinate the work of numerous branches or other sub-divisions, its answer is not dissimilar to the WSM Delegate Council (DC);

Executive Committee of the Union.

“The following functions will be ascribed to that Committee: implementation of decisions made by the Union, as entrusted; overseeing the activity and theoretical development of the individual organizations, in keeping with the overall theoretical and tactical line of the Union; monitoring the general state of the movement; maintaining functional organizational ties between all the member organizations of the Union, as well as with other organizations.”

However because of the administrative contradiction outlined above was an ongoing tension where WSM DC was expected to somehow solve the consequences of our failure to collectively understand the differences between the four points above. Those who later went on to become social democrats wanted DC to micro-manage the organisation’s work - at a level impossible without ‘full timers’ - and as part of this micro-management the requirement to pass on all sorts of decision making powers to DC.

The social democrats later interpreted their failure to make DC work in the manner wished as a failure of anarchism. In particular they came to adopt the idea that such decision making roles were only suitable for an elite of people with the right sort of brains. To be clear they were far from the first set of people for whom the Platform proved a transition out of anarchism to more elitist politics, to my mind this is because the Platform has often been implemented as a program for a cadre organisation.

Does any of this still matter in the age of the ‘networked individual’?

There is a final point, and that is to ask whether an organisational set of principles from the year when public telephones first appeared in Dublin train stations has relevance in the age when many of us have instant global video communication devices sitting in our pockets. The transformative opening up of ‘one to many’ communications in the last decade has radically changed the way oppositional movements emerge. The central part once played by the old left party system in monopolising ‘one to many’ communications in oppositional politics no longer exists. We are only beginning to see how that will transform the left but the question has to be asked whether this means the organisational principles of the Platform are about as relevant as designs for a horse and cart today.

I’d suggest that perhaps the Platform is more relevant than ever precisely because the communication monopolies that once made centralised, top down party structures seem natural no longer exist. Let’s rewrite the 3rd paragraph of the platform quoted at the start of this piece slightly to refer to more recent events. ‘In every country the Occupy movements were represented by local organizations with contradictory theory and tactics with no forward planning or continuity in their work. They folded after a time, leaving little or no trace.’ This suggests how the problems of informal anarchism of the 1910s have become more general movement problems today. But it also enables us to see how the negative costs of such disappearance are not what they used to be because online communications and archiving makes it much more possible to preserve both lessons and communications networks. Occupy and the other horizontalist movements didn’t simply vanish, they often seeded other movement’s.

An important qualifier is that the horizontalist movements may share organisational features with the informal anarchists of long ago but they did not define themselves as revolutionary organisations en route to overthrowing capitalism. From that point of view the way the Platform talks about the relationship between the Platformists and the mass semi-spontaneous movements of its day are informative “We regard revolutionary syndicalism solely as a trade-union movement of the workers with no specific social and political ideology, and thus incapable by itself of resolving the social question; as such it is our opinion that the task of anarchists in the ranks of that movement consists of developing anarchist ideas within it and of steering it in an anarchist direction, so as to turn it into an active army of the social revolution. It is important to remember that if syndicalism is not given the support of anarchist theory in good time, it will be forced to rely on the ideology of some statist political party.”

The post 2011 period is precisely a period where ‘horizontalism not given the support of anarchist theory in good time, [was] forced to rely on the ideology of some statist political party’ in the forms of Syriza, Podemos and much less convincingly the old left of Sanders & Corbyn. This was a failure of the weakness and general disorganisation of anarchism in 2011 - it failed to provide a convincing alternative. Worse some made the mistake of reading the failures of Occupy as being failures of anarchism. Some of the informal anarchists in Greece, Spain and elsewhere ended up being sucked into becoming voters if not foot soldiers of those new statist political parties.

Resisting those tendencies would have required quite sizeable and well resourced formal anarchist organisations with the reputation and reach to successfully argue for other paths than the retreat to electoralism. Building those sort of organisations is not the work of weeks or months, nor can they rapidly emerge from nowhere. Rather we need to spend time building the required tight relationships and deep levels of skill and experience on a large enough basis to give us the needed reach when popular movements explode onto the scene. The Platform continues to provide a starting point to understanding how that is done.

Where does that leave the WSM today with regard to the Platform?

The ‘Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists (Draft)’ remains a useful foundational document even if its certainly not the text you would hand to someone explain what the WSM stands for. It’s particularly useful for anarchists who have become frustrated with practises of anarchism that are based around informality as a demonstration that informality is not fundamental to anarchism. The danger here is that for such people it is often also the last step before they break with anarchism, so the historical experience has been that hitting a barrier often results in just such a break. Critics then reverse cause and effect and portray the platform as some sort of exit text.

It’s useful as a tool of common identification with other anarchists internationally. In both cases its pedigree is important as those who drafted it were quite central figures in anarchism of the 1910s and 1920s. But that is quite a specialist usage that also has the downside of only working for those who have a rather detailed knowledge of what many consider to be an obscure corner of anarchist history. Out of necessity WSM has relied almost completely on such an approach to identify potential international allies, the exceptions being where direct individual contact generated the level of knowledge and mutual understanding that could bypass that.

As with all foundational texts it’s important to be hyper aware of the tendency to treat them as scripture or material for ‘appeal to expertise’ style of arguments. And the related danger of presuming that anything not touched on is not of major importance. As discussed already the huge shortcomings of the platform is not in what it says but what it doesn’t say, it had nothing to say about how other oppressions intersect class. Or, although this is a modern concern, the related questions of environmental crisis and growth requiring economics.

The Platform is not anything approaching a manual, quite the opposite it’s a sketch of some ideas that will only become useful as a guide when they are considerably fleshed out and built on. It’s central ongoing strength, perhaps unfortunately, is its description of the shortcomings of informal anarchism in the opening paragraphs and the sketch it provides of organisational structures and methods to overcome those shortcomings. Without those anarchism remains trapped as a critique of the left without the accompanying methods to aid the birth of a genuinely free society.

That at the end of the day is the relevance of the platform. We stand on the shoulders of a fight for freedom that is hundreds of years old and in certain respects thousands. That is a fight that has not been won and broadly we have lost for two reasons. The first because rebellion resulted on the promotion of new people into power, people who promised freedom but who at best simply modifyed the prison. And the second because we lacked the organisation to defeat the old regime. Most of the left tends to focus simply on that second problem, many in the anarchist movement fear the first to the extent it makes the second inevitable. The platform claimed to provide the route to freedom overcoming both.

WORDS: Andrew Flood (Follow Andrew on Twitter )

Thanks to everyone who contribtued to this draft either at the branch meeting or when I shared an early version for comments (and proof reading corrections).

Relevent further reading

You can read the modern translation of the platform from which quotations above are taken http://www.anarkismo.net/article/1000

WSM PP: Anarchism, Oppression and Exploitation - http://www.wsm.ie/c/anarchism-oppression-exploitation-policy

WSM PP: Role of the Anarchist Organisation - http://www.wsm.ie/c/role-anarchist-organisation-policy

The WSM & fighting the last war - a reply to James O’Brien - http://anarchism.pageabode.com/andrewnflood/wsm-history-reply-james-obrien

Making anarchist organisations work - Dunbar’s number, administration and care - http://anarchism.pageabode.com/andrewnflood/anarchist-organising-dunbars-number

Solidarity, Engagement & the Revolutionary Organisation - http://anarchism.pageabode.com/andrewnflood/solidarity-engagement-revolutionary-organisation