Over 30 years of anarchist writing from Ireland listed under hundreds of topics

Single Issue Campaigns, Community Syndicalism & Direct Democracy

There’s been a lot of talk lately about participatory and direct democracy. Renewed interest in alternative forms of organising society has arisen from increasing dissatisfaction with mainstream politics and the domination of the economy by a few corporations. This dissatisfaction has found its expression in the Arab spring, the May 15th movement in Spain and the Occupy movement in the English-speaking world. Where the anti-capitalist movement of the last decade focussed almost exclusively on the power of the corporations and finance capital, this current tendency is to also focus on politics and the state.

There’s been a lot of talk lately about participatory and direct democracy. Renewed interest in alternative forms of organising society has arisen from increasing dissatisfaction with mainstream politics and the domination of the economy by a few corporations. This dissatisfaction has found its expression in the Arab spring, the May 15th movement in Spain and the Occupy movement in the English-speaking world. Where the anti-capitalist movement of the last decade focussed almost exclusively on the power of the corporations and finance capital, this current tendency is to also focus on politics and the state.

The movement in the English speaking world has exhibited many difficulties: The rejection of previous organisational forms and aversion to traditional politics, while understandable given the history of the authoritarian left, has led to any political philosophy with a historical basis being shunned. The result has been that a new generation of activists have been fumbling in the dark for a way to change society, unable to see the writing on the wall: “Not all old ideas are bad ideas”.

Another problem has been the tendency to start with general, sometimes abstract demands. Demanding direct democracy doesn’t mean much to a person whose main concern is keeping their children fed and clothed, while demanding the IMF get out of Ireland is all very well but it’s at best aspirational and doesn’t really come with an alternative. So how do we make the demand for direct democracy relevant to day to day life? How do we make people see the necessity of fighting against capitalism and the state?

Non-Hierarchical

Anarchists believe it is important to oppose hierarchy in all its forms and replace the current socio-economic system with a democratic non-hierarchical society. This would entail the replacement of top-down managerial structures in the workplace and authoritarian forms of power such as the state, but we don’t expect people just to start waving red and black flags because we’re sure we’re right. We want people to see for themselves what Anarchism is like in action. The presence of Anarchists in campaigns helps spread libertarian ideas and show their superiority to organisational forms advocated by authoritarian socialists.

There are three main reasons for Anarchists to get involved in single issue campaigns: To show that Anarchist methods can work in practice, to give people a sense of their own power, and, ultimately, to build horizontally-structured organisations capable of replacing hierarchical state and corporate systems. Moreover the involvement in struggle is a learning process for experienced organisers and first time activists alike. Only when ideas are put to the test can we see which ones are relevant and which aren’t. Last year many different ideas of what direct democracy entailed were tested by the occupy movement. Some embodied the tyranny of structurelessness and led to small informal leaderships taking over, while others provided an example of how tightly organised structures can work in practice. The problems of fetishising the consensus process were also exposed as it was found to be a cumbersome and often undemocratic form of decision-making.

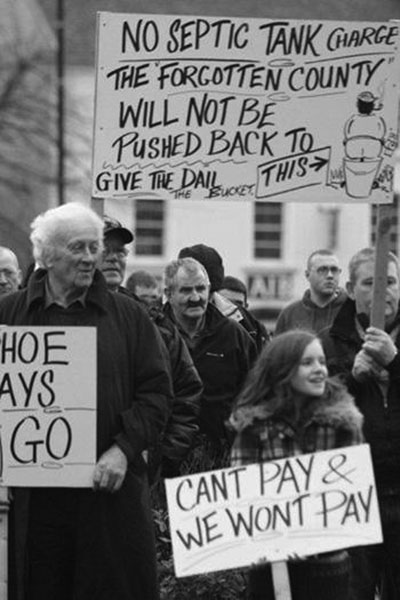

The main lesson that those involved in social struggle will learn, however, is that the State and capital, with their many tentacles of control, are not on our side. First-time activists in the Campaign against Household and Water Taxes will have learned that the mainstream media is not there to report the truth, but rather to put across whatever message is desired by the state and corporate media bosses. Throughout the campaign, RTÉ have shamelessly presented the government’s fudged figures as fact and halved the numbers involved in the protest at the Fine Gael Ard Fheis in their report of the event. The role of the Gardaí was revealed to some of those who attended the protest at the Labour Party conference, when pepper spray was used against activists.

Democracy?

More generally, the campaign has revealed that despite what we were brought up to believe, the state is not what democracy looks like. More people are boycotting the Household Tax than voted for the Government. It wasn’t in the manifestos of the governing parties, so no one voted for it. Yet there is no sign of it being abolished and those who refuse to pay are being threatened with court appearances and large fines.

More generally, the campaign has revealed that despite what we were brought up to believe, the state is not what democracy looks like. More people are boycotting the Household Tax than voted for the Government. It wasn’t in the manifestos of the governing parties, so no one voted for it. Yet there is no sign of it being abolished and those who refuse to pay are being threatened with court appearances and large fines.

When people see that the state is not on our side, that it is not even a neutral intermediary between us (the majority) and them (the wealthy minority), they begin to see the importance of building an alternative society, and involvement in campaigns that utilise direct action can give them a sense of their power to do that.

As the Italian Anarchist, Errico Malatesta wrote:

“Whatever may be the practical results of the struggle for immediate gains, the greatest value lies in the struggle itself. For thereby workers learn that the bosses interests are opposed to theirs and that they cannot improve their conditions, and much less emancipate themselves, except by uniting and becoming stronger than the bosses. If they succeed in getting what they demand, they will be better off: they will earn more, work fewer hours and will have more time and energy to reflect on the things that matter to them, and will immediately make greater demands and have greater needs. If they do not succeed they will be led to study the reasons of their failure and recognise the need for closer unity and greater activity and they will in the end understand that to make victory secure and definite, it is necessary to destroy capitalism. The revolutionary cause, the cause of moral elevation and emancipation of the workers must benefit by the fact that workers unite and struggle for their interests.”

[Malatesta, Errico Malatesta: His Life and Ideas, p. 191]

Identifying the problem also poses the question of a solution. Organising their own campaigns not only gives people confidence but it also gives them the skills necessary to create and administer a society that is designed to meet their needs. If struggle is a school of self-governance, then the means employed must correspond to the desired end. This is one area where Anarchists are often at odds with authoritarian socialists. The latter believe that in order to achieve socialism there must be a vanguard party, with “the correct leadership” directing struggle from above. While they often give lip service to workers’ democracy, this usually either means that they will put that into place sometime after they take power or that it equates to the power of the vanguard party. Authoritarian methods of organising resistance, however, can only give birth to authoritarian “revolutions” and new forms of authoritarian society. A movement that does not trust the working class to direct its own struggles, to create the type of society that reflects its desires and needs, will not easily relinquish power after it has seized it in the name of the class. Just as a truly socialist society would mould itself around people’s needs, so too must the way we fight for that society.

Issues and Solutions

Community syndicalism (or unionism) is a process of creating the structures of a new society within the old. It involves people organising locally to raise issues affecting the community and finding solutions to them. It encourages all members of a community to involve themselves in tackling the issues that they face in their daily lives without the need for the intervention of so-called representatives like TDs or councillors. It creates a localised form of dual power that is counterposed to traditional hierarchical forms. Community syndicates can also provide valuable support for strikes in the field of industry.

The community syndicate would ideally be based upon the mass assembly of members, where issues like local services, education, rent etc. could be debated and decisions made on how best to win improvements. Beyond the locality, the syndicate should federate with similar organisations in other areas to collaborate on campaigns that have a wider scope. Each syndicate would send delegates to the federal assembly with a strict mandate and the right to recall and elect new delegates in their place if they abuse their mandate.

A recent example of community syndicalism in action comes from the 2001 revolt in Argentina. Local assemblies were set up and federated to co-ordinate struggles. They occupied buildings and created communal kitchens, community centres, day-care centres and built links with occupied workplaces. As one participant noted people “[began] to solve problems themselves, without turning to the institutions that caused the problems in the first place.” The neighbourhood assemblies ended a system in which “we elected people to make our decisions for us . . . now we will make our own decisions.”

The History of the CNT in Spain, particularly in Catalunya, is littered with examples of community syndicalism in action. The CNT is usually thought of as primarily an industrial union, but at one time it had strong organisations in every working-class neighbourhood in Barcelona. This was made possible by the reorganisation of the confederation at its 1918 congress where district committees based in union centres in the neighbourhoods were established. Organisers were known as “the eyes and ears of the union in the neighbourhood”. Within a year the national membership had doubled to 715,000, with 250,000 alone in Barcelona. Organising in this manner provided valuable support for the industrial unions of the confederation. In 1919 a strike broke out at the Ebro irrigation and power company after a small number of workers were sacked for union membership. In response, all CNT power workers walked off the job. The local federation mobilised and what started as a small-scale industrial dispute turned into open class war on a city-wide scale. Chris Ealham writes in his book Anarchism and the City: Revolution and Counter Revolution in Barcelona 1898 to 1937 that “much of the state’s repressive arsenal was mobilised; martial law was implemented and following the militarization of essential services, soldiers replaced strikers and up to 4,000 workers were jailed.” (pp 41.)

However, the CNT’s vast network of neighbourhood syndicates allowed it to raise financial support and requisition food and other essentials. The strike was able to hold out long enough to cripple industry in the city and the state was obliged to step in, forcing the power company to capitulate to the demands of the CNT which now moved beyond the reinstatement of the workers and union recognition to pay rises, the payment of wages lost during the strike and an amnesty for all those involved in pickets. Furthermore, the strike created such fear among the ruling-class that the government became the first in Europe to introduce the eight-hour day in an attempt to avoid further class conflict. What began as a single issue was generalised into a battle for improved conditions for workers all over the city.

In 1931, the CNT led a rent strike in Barcelona, which demanded a 40% rent decrease. This began with a mass meeting on May 1st and by August there were 100,000 participants. As well as the boycott of rent, they organised to resist and reverse evictions. Many landlords, finding their income streams drying up, gave into the demands and waived unpaid rents from the period of the strike.

More recently, and closer to home, the Anti-Poll Tax Federation in the UK and the anti-water tax campaign in Ireland were organised along lines that closely resembled community syndicalism. In the case of the former campaign, some local groups outlived the single issue. One of these still in existence is the Haringey Solidarity Group. They are far from being a mass community union but they do have a contact list of thousands and campaign both on local and broader issues.

Lessons

Of course, there is no point in citing historical examples if we do not draw lessons from them that we can apply to the present. There are obvious differences between Barcelona in the first half of the last century and Ireland today. The example cited in Argentina took place during a period of revolution, not a single issue campaign and the Haringey Solidarity Group organised at a time of defeat for the working-class.

Of course, there is no point in citing historical examples if we do not draw lessons from them that we can apply to the present. There are obvious differences between Barcelona in the first half of the last century and Ireland today. The example cited in Argentina took place during a period of revolution, not a single issue campaign and the Haringey Solidarity Group organised at a time of defeat for the working-class.

Today, the Campaign against Household and Water Taxes in Ireland is organised on a national scale. At the moment, in places its organisation resembles an embryonic form of community syndicalism. It’s at its best where activists groups are organised in a directly democratic manner, where all members who wish to participate can and all have equal say in decision-making. Many local areas have begun the process of federating, with mandated delegates being sent to county-wide meetings.

With the announcement that water meters will be installed by the end of the year and will have to be paid for by householders, it is clear that this will become a protracted battle. Within the campaign, the battle will be between democratic and authoritarian methods of organising. In communities, the battle will be to win non-payers to the idea of local activism. With the right structure and a mass campaign membership, what is already the biggest boycott movement the country has seen since the Land League could be a force with far more power than any so-called workers’ party participating in elections could ever achieve.

With a victory under its belt, or even by holding its own in a long, drawn-out struggle, such an organisation could draw other groups under its wing. By drawing in workers engaged in occupations such as the Vita Cortex workers, it could begin to develop an industrial wing. Working with groups like unlockNAMA, which is already organised along directly democratic lines, could lead to the opening of community centres and, in harsh times, communal kitchens. Such an organisation could eventually by pass the bureaucratic monoliths that are the mainstream unions and organise strikes.

Ultimately such an organisation would be a libertarian communist society in embryo. It would have to overcome modern problems such as suburbanisation and rebuild the idea of community, but if organised in every neighbourhood, along with an industrial wing it would have the wherewithal to bypass the capitalist state and create a new society within the old.

Of course this would inevitably bring it into open conflict with the state. It would be the role of an Anarchist organisation like the WSM to work within such an organisation, to spread the revolutionary anarchist idea that the state cannot just be bypassed, it must eventually be smashed or it will ruthlessly crush us and our movement.

All this is aspirational, but it is possible if we put all our efforts into building community syndicalism. If we win the argument for libertarian ideas in the Household Tax Campaign we have the opportunity to build a powerful national federation of communities and workers. There is no point in having a new world in our hearts if we don’t strive to create it in the here and now. This is just the beginning.