Over 30 years of anarchist writing from Ireland listed under hundreds of topics

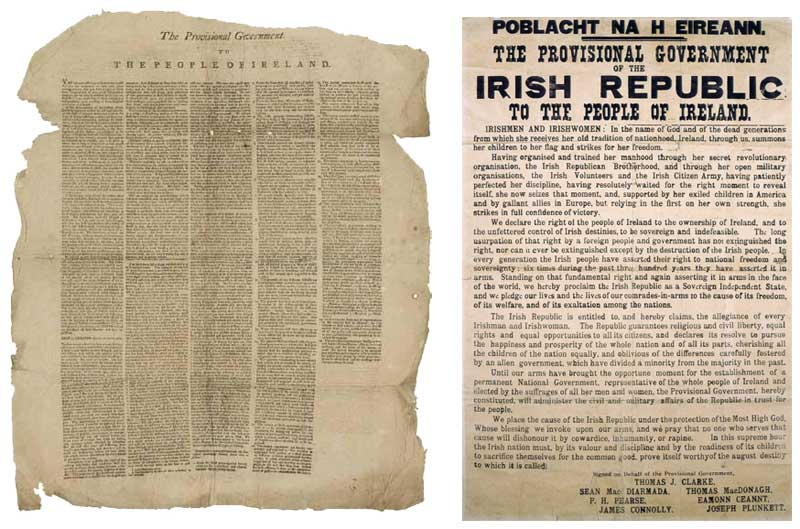

The Fenian Proclamation (1867) vs the 1916 Proclamation - the lost radicalism of Irish republicanism

Considering the fact the Anarchist Communism as a coherent and easily transmutable ideology only came to be during the 1870’s and 1880’s the Fenian Proclamation of 1867 is striking in its progressiveness and clarity of thought. A product of the Irish Famine, English economic and military Imperialism in Ireland and a tradition of insurrectionary attempts against Imperialist rule, the original Fenians of 1867 should be viewed as proto socialistic in their values and analysis.

Considering the fact the Anarchist Communism as a coherent and easily transmutable ideology only came to be during the 1870’s and 1880’s the Fenian Proclamation of 1867 is striking in its progressiveness and clarity of thought. A product of the Irish Famine, English economic and military Imperialism in Ireland and a tradition of insurrectionary attempts against Imperialist rule, the original Fenians of 1867 should be viewed as proto socialistic in their values and analysis.

This is not to say they were Anarchists or close, they were most definitely Republican statists, who organised for an almost purely military strike against Imperialism, as opposed to the destruction of the state and working class/farmer self-activity for the destruction of exploitation and Imperialism and the creation of a cooperative society.

It is worth however comparing the much more well known 1916 Proclamation against the Fenian Proclamation of 1876, in order to highlight the Nationalistic, bourgeois turn of the mainstream republican movement in Ireland away from traditional Fenianism. The 1916 proclamation should remain an important point in our history, but like anything, it is not above critical analysis-what forces produced it, the context it was wrote in and how it affects our present. As the thinking and history of the period is still very much influential for todays Republican movement it is especially important to critically analyse it. Without a proper understanding of such a pivotal time and the influences it has today we cannot even attempt to shape the future.

Background to the 1916 Proclamation.

Toward the end of the 1800’s the role of the Catholic Church was central to the popular interpretation of the 1798 Rebellion as a fight for ‘Faith and Fatherland’ and as ‘’Nationalist defenders’’ against foreign influence.This interpretation was the polar opposite to the secularist radical republicanism of the Irish Republican Brotherhood which traced its origins to the Fenians and further back to the Society of United Irishmen and the French Revolution.

While the Catholic Church in Ireland, as elsewhere, had opposed the revolutionary violence unleashed by the French Revolution, a century later it viewed the Irish Rebellion of 1798 as a struggle of the Irish Catholic people for their religion against alien oppression.The stress was on the cruelties of the British colonial establishment and the suppression of Religious rights. A leading propagandist for this romantic, clericalist and nationalist interpretation was Father Patrick Kavanagh, a Franciscan historian. The arguments were largely a reaction against the Irish unionist interpretation of the Rebellion as a manifestation of Catholic sectarian savagery--an interpretation maintained to this day by ‘West Brit’ and Unionist sectors of Irish Society.

Kavanagh’s popular history of the rebellion was re-issued several times since the 1870s and formed the interpretation which lay behind the 1798 commemorations in County Wexford. It was during this period that Republicanism became infused with Nationalist and Catholic defender sentiments. Kavanagh stressed the role of the church as friend of the people and of heroic priest leaders, like Father John Murphy of Boolavogue- despite the fact that the church overwhelmingly opposed the rising and it was only a tiny minority of non-compliant priests who took part. Kavanagh's history of 1798 was first published in the aftermath of the failed Fenian rising of 1867, and quickly became the popularly accepted account of 1798.

In the years after ‘the Great Famine’ the Catholic church had something of a strangle-hold on Irish life meaning it had the social weight to shape public opinion to a large degree.

The 1898 celebrations which took place throughout the county had a strategic political angle at the time, and dominance for centrality in the celebrations was hotly contested. Different political groupings vied for control to commemorate the rising, even within the Nationalist camp Leaders such as Redmond and Dillon competed for control, but, overall, it was the Nationalists who won the fight over radical Republican interpretations of the Rising.

The commemorations were not just a remembrance of historic events, but were used by a growing nationalist movement in the 1890s, centred around the politicians of the Irish Parliamentary Party to project their ideology. It was an alliance of grassroots Catholic and nationalist forces-one that has largely remained in the Republican movement, in some form, to this day.

These events, along with the Celtic revival greatly influenced Republican movement at the time, sowing the seeds for what would become the thinking of the modern Republican movement. This 30-40 year period after the 1867 rising is of utmost importance for understanding the modern Republican movement. It was a time when Republicanism became imbued with overtly Nationalist sentiments at an ideological and leadership level. Meaning that today the terms Nationalist and Republican are more often than not, used interchangeably.

Interestingly this was also the period when the modern form of the Republican movement came into being, an open (Republican/Nationalist) party --opening the road to constitutional, electoral politics--, twinned with a conspiratorial militant secret wing and involvement by members of the Catholic clergy in Nationalist issues.

A broad church movement, its single unifying core is the removal of British administration in Ireland--unlike the Fenians--and the establishment of a 32-county unified Irish state as an end goal. While many have attempted to slip in Socialist thought and a general form of anti-Imperialism into the movement, every attempt has failed to become mainstream. It would rip apart the Republican-Nationalist movements very ideological and organisational base to make such a change (as was seen in the late 1960’s).

The Republican-Nationalist movement has had to continually re-found itself over the last 100 years as forces within began to question the vast ideological inconsistencies of the movement--most eventually abandoning Revolutionary politics altogether and joining the enemies camp as the inconsistencies mounted, others abandoning mainstream Republicanism for the minority Socialistic trends which re-grouped outside of the movement or create short lived small ‘Socialist-Republican’ organisations.

This is a direct result of the absolutist and binary nationalist model proposed by ‘traditionalist’ (largely meaning Nationalist) Republicans, a kind of all or nothing style of outlook, nothing in between, or outside that model is given serious consideration. Along with the mimicking/mirroring of the hierarchical structures of British dominance, this thinking is based in the world view of the Nationalist fervor of the 1910’s, compounded over the years by a bunker mentality that was sustained by state onslaughts against the movement.

This is not just a theoretical or historical comparison over the wording of two historical documents but is central to understanding the modern Republican movement.

It will be highlighted by comparison that it was the ethos, thinking and ideology behind the 1916 Proclamation that won out and stills forms the backbone a Republicanism in Ireland today. If the major influence had been the 1867 proclamation we would be looking at a very different Republican movement today, possible even an explicitly Socialistic one--instead of Socialist thought forming a tiny minority trend within the wider republican family.

The first quote comes from the 1867 Fenian Proclamation, the second from the 1916 document.

"complete separation of Church and State" ,as opposed to, "In the name of God", "We place the cause of the Irish Republic under the protection of the Most High God, Whose blessing we invoke upon our arms," ect, clearly theres a logical contradiction between these two quotes, one could quite possible would lead you down the rational, scientific, even atheistic route—the other the religious, even zealotry route.

"and we declare, in the face of our brethren, that we intend no war against the people of England"—clearly anti-nationalist, leaning towards national liberation as opposed to "The long usurpation of that right by a foreign people and government", these are two very different statements, one gracious anti-nationalism, the other bordering on xenophobia and open nationalism. The inclusion of "a foreign people" clearly associates the ordinary working class of Britain with the imperialist expansionism of its Capitalist government. As reactionary nationalist as it gets.

"which shall secure to all the intrinsic value of their labour. The soil of Ireland, at present in the possession of an oligarchy, belongs to us, the Irish people, and to us it must be restored.","– our war is against the aristocratic locusts, whether English or Irish, who have eaten the verdure of our fields – against the aristocratic leeches who drain alike our fields and theirs."—clearly socialistic and explicitly anti-Nationalist here, maybe even implying Davitt style decentralised land ownership and definitely including explicit class warfare against all exploiters, irrespective of nationality, as a central part of struggle for freedom--something unimaginable within the mainstream Republican movement today.

While the 1916 document gives one short line, that in the context of the rest of the document doesn’t mean much, "We declare the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland,’’—this could mean anything from socialist to capitalist ownership, and anything in between and in the context of the rest of the piece and what happened after the war of independence--most likely reactionary Capitalistic.

There are at least 5 socialistic references/lines in the Fenian document as opposed to one vague in relation to "ownership" in the 1916 document. This is a common trend within the 1916 document, it is somewhat vague while the 1876 document leaves little room for doubting who it considers the enemies ( "aristocratic leeches" ) and therefore the implicit proposals for a new Ireland. The vagueness of lines such as "cherish all children of the nation equally", especially with the continuous references to "God", easily lead many, of an already unscientific, traditional Catholic nationalist mindset to see no contradiction with harsh anti-choice positions, while still formally subscribing to traditional ‘republican’ concepts such as individual liberty.

"Republicans of the entire world, our cause is your cause. Our enemy is your enemy. Let your hearts be with us. As for you, workmen of England, it is not only your hearts we wish, but your arms."—clearly internationalist, expressing solidarity beyond borders ect, as opposed to, "and by gallant allies in Europe,"—which referenced military support republicans in 1916 received from Imperialist Germany, which was forthcoming only as part of Germany’s strategic war efforts in Europe. Considering the fact that mainstream Republicans made close contacts with Nazi Germany during the second world war in order to further their national ambitions, this discrepancy between a solidaristic Internationalist position in the 1867 piece and the mention of collusion with foreign Imperialists in the 1916 piece should not be taken lightly.

"We therefore declare that, unable longer to endure the curse of Monarchical Government,"—This is clearly French republican style sentiment, nowhere in the 1916 document is Monarchy mentioned, while nationalist sentiments are throughout it.

The only similarities between the two documents are their assertion of the right of subjected populations to national liberation through force of arms (something Anarchists would agree with) and their explicit statism for the creation of a new hierarchical political system, separate from that of the Imperialists.

Despite many Republicans claiming otherwise there is nothing hugely contradictory about the ideology of the 1916 document with the nationalist ideology and political disposition of groupings such as the Blueshirt Fascists in the 1930’s, the collusion with Nazi Germany or the establishment of the 26 county republic as a "stepping stone" to national liberation--all of these moves could be justified by one part or another from the ethos of the Republicanism of the 1910’s, which had significantly moved away from its Fenian roots.

Guest writer: Stephen Heart