Over 30 years of anarchist writing from Ireland listed under hundreds of topics

Interview with Larry Wheelock: “No Justice, Just Us”

In what will be widely seen as a part of an ongoing cover up the the Gardai Ombudsman has released a report which claims Terence Wheelock was not mistreated in Store street Gardai station (where he died). Here we reproduce a long interview with his brother Larry who, along with the rest of the family, has spent years campaigning for justice for Terence.

---

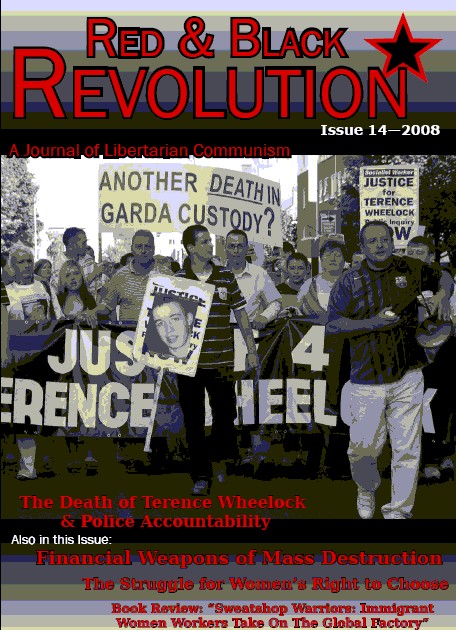

The family and friends of Terence Wheelock are still waiting for a credible and complete account of what happened in the station from the Garda [1] . In 2005 they launched a campaign demanding an independent inquiry into the case.

By tirelessly pushing the case in the media and organising meetings, protests and vigils they have managed to build a well supported and highly visible justice campaign based in Dublin’s north inner city, a working class community that has long suffered from heavy handed policing. The Justice for Terence Wheelock Campaign (JTWC) is currently the only such initiative that has managed to ask questions about the nature of policing in Irish society for any extended period of time [2] and because of that has become a reference point for other families who have experienced police brutality across Ireland.

The WSM and other Irish anarchists actively support and are involved in building support for the family’s campaign. In this interview, Terence’s brother Larry Wheelock, the main spokesperson for the JTWC, a determined man in his thirties, offers an in-depth and intimate account of his brother’s life and death, and his family’s ongoing struggle for justice.

Posters featuring Terence Wheelock’s face have become a common sight on Dublin walls and lampposts and his name is now used as shorthand for the general experience of Garda brutality amongst people from his community. Paradoxically, the fact that he has become iconic may have served to obscure his life so we began the interview by asking Larry to describe his brother when he was alive.

“My brother…was born and lived in the north inner city. He was very happy-go-lucky, loved sport, he was articulate and very, very bright” and completed his Junior Cert. and Leaving Cert [3] .

Terence was particularly good at maths and loved history and was “very artistic – he loved to paint and draw”. Despite being popular his brother points out, “He wasn’t the life and soul of the party and he wouldn’t’ve stood out in the crowd. He was more the fella at the back who stood and watched”. Asked about his interests his brother says “He was a mad Liverpool supporter and Tupac was who he was into”. Terence got on well with all the members of his large and close knit family and in particular, “He was very close and very protective of Gavan his younger brother”.

It is impossible however to describe the shape and texture of Terence’s life without some reference to the police and the courts.

Like a large number of young men in his area, he began to get into trouble as he entered his teenage years. Larry remembers that “Terence was at a very delicate age at about 13…and would have been getting in with the wrong crowd. He was by no means a hardened criminal. Impish behaviour, you know, things that idle young lads get up to. Things that would be very normal in the area, not by everybody, but in most working class areas there is the gang at the corner”. Predictably enough these early experiences established a pattern and Terence found himself in and out of trouble over the next few years. “He was probably arrested first when he was about thirteen. He would’ve seen what a lot of young kids would’ve come across at that time.

Public relations with the police were…dire and probably a lot of people in the north inner city would have been very badly treated by the police”. When discussing the interaction between youths and the police on the streets, Larry is quick to note that minor anti-social behaviour “is not just endemic to working class areas. I have seen it in middle class areas but I have seen how the same problem in different localities is handled differently by the police”.

Larry is emphatic that Gardaí show “total disrespect for lads in working class areas. I think ninety percent of the Garda join wanting to do good but they end up in the inner city and [get] corrupted along the way…It becomes ‘these are all scumbags’, ‘treat these in a certain way’ and the attitude is ‘everyone is a criminal in the north inner city’. This understandably had an impact on Terence and “he knew full well what the police do to people in the north inner city and their attitude to people in the area and he had his fair share of beatings [from them]”.

Larry says “I could see he was heading for that type of life and I was trying to turn him off by tell- ing him about my experiences” but aggressive policing, circumstances, Terence’s age, natural sense of pride and rebelliousness set him on a course in which police harassment and legal problems became part of the fabric of his everyday life. In fact, less than two weeks before his fateful arrest during a minor incident “they [the Garda] had hurt his arm badly” leaving it fractured and swollen.

Despite the fact that Terence found himself enmeshed in legal problems and hassle from the Garda, Larry explains that his brother was trying to get out of trouble. “Terence had only done a safety pass [4] . He wanted to do an apprenticeship with Robbie [one of his older brothers] as a carpenter. He had a path in his mind”. He also talked to his mother about moving away from the area. Larry reflects on the fact that Terence was already aware of the cost of finding himself at the wrong side of the law commenting that, “When you get locked up at say 16 you are still 16 at heart. Your life stops but all your friends move on so when you come out they all have kids and have settled down so you kind of get disillusioned”.

Terence’s arrest and injuries

Terence’s plans were, of course, never realised and the gravitational pull of circumstances ultimately led to situation in which Terence was left fighting for his life and his family’s life turned upside down.

“It was the 2nd of June. It was a Thursday morning and Terence woke up and…he started to decorate his room and he went to get a paintbrush”. Before going to the shops “he went to get a pump from his neighbour because his bike had a slow puncture”. Unfortunately for Terence, a stolen car was being stripped nearby and the police arrived on the scene.

Family members and neighbours are adamant that Terence had nothing to do with stealing the car and nothing to do dismantling it. Nonetheless, Terence was arrested with three other young men on suspicion of being involved in the robbery of the car.

It was late morning on a sunny day and as a consequence there were a lot of witnesses from whom Larry has pieced together what happened during the first couple of minutes of the arrest. “They put handcuffs on behind his back. They know his arm is very badly damaged.

“It was very badly swollen and the cops arresting him were the same cops who did it to him ten days before. They bend his arms up and he pushes back and says ‘let go of my arm you are killing me’”. There is a minor scuffle and he is hauled into the van. His brother Larry arrives at this point. “A girl is shouting ‘leave him the fuck alone’ and other people are saying ‘Terence is getting nicked’. I heard the bang, the bang of his head being hit off the van”. (It was later confirmed during a sitting of the Coroner’s Court [5] by the other man in the van that

Terence was assaulted and his head was banged off the side of the van). Nothing much happened following this except some minor banter between Terence and a Garda on the way to Store Street station. I ask Larry if he was concerned at this point and responds in the negative, explaining that he thought “he has nothing to do with it so he will be out in a couple of hours…I did think he was going to being remanded in custody but I was not worried”.

At the station “they bring him in and they strip search first and they were trying to humiliate him. The cop says [in evidence at the Coroner’s court] he doesn’t react.

I find this very strange. This is a bit ‘too’ honest because Terence would react to this”. Larry says it is significant that “the only bruising noted on the custody records is on his arm”. Also he finds it noteworthy that the Gardaí claim that “every seven minutes, they check him and he is asleep but Terence only woke up a couple of hours before, after a night’s sleep!”

Although the exact course of events in Store Street remains shrouded in mystery, two other detainees report hearing a commotion. A little later, Larry recounts, a new prisoner reported hearing a Garda saying “Get a knife. There is a fella after hanging himself” but that it seems staged to him.

Larry notes there are even different versions of what the Gardaí did then with one Garda claiming that Terence was cut down and another saying he was supposedly lifted off the suspension point. He is then brought into the hall. Again “one said he is lifted out and the other says he dragged him”. Indignantly, Larry asks “If a fella had a neck injury why would you drag him out?” Whatever happened while Terence was in that cell, he left Store Street in a coma. The family was then notified that Terence had tried to commit suicide.

Larry says, “I didn’t believe it and I thought Terence might be feigning something after a bad beating – that he was acting. My ma was worried…she got a mad feeling in her stomach, in her womb, a mad empty feeling is how she described it and says ‘I hope he is alright’”. Oddly, the police bring Terence’s mother to the wrong hospital on the south side of the city away from the station.

Eventually, when this was cleared up, the family gathered in the Mater hospital on the north side where Terence was being treated. Larry describes the scene, “All my sisters were in bits…My da was the last one to get here except for Marcus [the eldest brother]. He says ‘they are after saying Terence hung himself’ and he falls into my arms”. At this point, the family were informed that a Garda investigation had already started into events in Store Street.

Instinctively they felt that Terence was an unlikely candidate for a suicide attempt as “he did not suffer depression”. Moreover, because he had been in custody before and was unlikely to have been rattled by being detained and significantly, he had been busy making plans in the house and had even bought clothes for a party the following night. Besides this and more worryingly Larry had seen him in a pair of shorts that morning and he had no marks on his body except for his damaged arm. In the hospital, he was covered with abrasions and bruises.

He takes up the story recalling, “Sinéad [one of Terence’s sisters] said ‘look at the way they left him!’. He had no control over his body and tears are hopping out of my face. And we call the doctor and we say we want him photographed straight away. His lip was burst and his knuckles looked swollen and there was a chunk gone out of the finger. I remember thinking how the fuck could he hang himself in them cells – I have been in those cells!” At this point, Larry brings out the grim photos of Terence in the hospital showing abrasions, swellings and bruises all over his legs and arms. “We got in touch with Yvonne Bambery [the family’s solicitor] and she comes to the hospital the next day and says…‘he didn’t do this to himself’.

She gets the custody records and applies to see the cell. When she went down three days later with an engineer, the cell was renovated and painted. It was cleaned as well. We found a statement months later taken by the Gardaí from a cleaner who was woken at 7 in the morning and was told she had to come down and surgically clean the cell”. Unsurprisingly, at this point the family decided to start a public campaign and begin legal proceedings to find out what had transpired in Store Street.

Terence’s death & the Garda harassment of the family

Terence remained in a coma for three months. This was an extremely difficult time for his family and Larry describes how “for a long, long time my mother was begging her son to live. ‘Fight Terence, fight!’ and believed Terence could hear her even when he was in a coma”. However, her son’s health slowly degenerated. “He was supposed to be dead on the Monday.

We were all sent for. He had double pneumonia in both lungs and a very low immune system because of what was done to his brain from oxygen deprivation. My ma was pleading with him not to die…even the doctors were shocked he survived so long. Then when my ma says ‘look son, I know that you fought very hard for me. Just go now to my da and ma’. She just walked out. He then died. It was almost as he needed permission to die”.

We discuss the funeral. Larry is proud to say that “we gave him a great send off” but “it shocked me to see to see how very visibly upset his mates they were – these would be considered tough young men but his friends were bawling out of their eyes as Terence’s coffin was carried up Seán McDermott Street. For such a short life, if you look at the attendance at his funeral he was well got, well liked.

I have yet to hear a bad word being said about him”. “I came back home I remember thinking to myself about people who come back to an empty home and feeling sorry for them. Later my brother Marcus came up. Terence slept with a T-shirt over his eyes and Marcus was so upset when he thought that he had nothing covering over his eyes.

I remember when Terence was born and my ma brought him home. I had him in my arms and I remember saying ‘Ma he has monkey feet!’ and then I remember him dead. I could not remember his life. All I could see in my mind was him being born and him dead. It was a weird thing. I tried to focus on that day on something in between but I couldn’t. It was my way of trying to be in control of a very bad situation.

I didn’t want to remember the funny bits, the happy bits, because I would’ve fallen apart. He was part of my life and now he’s not in my life”. Reflecting on the impact this has had on him personally, Larry remarks “I cried every day when Terence was in hospital and when he died I promised I would not cry again until he got justice. I haven’t cried since. I suppose I grieve in my sleep”.

The situation was made more all the more stressful because the family was subjected to a campaign of police harassment before and immediately after Terence’s death. Much of this took place outside the family home and at one point “there was between two and ten guards outside the house with dogs and horses. It was surreal”.

Larry says that there were charges drummed up against family members and ASBOs served against those in the area who actively supported the campaign. On several occasions, Larry says he was taunted about his brother’s death by local Gardaí, including officers making choking and hanging gestures. This culminated with a raid on the family home during which the Wheelocks were subjected to verbal and physical abuse. This proved too much to bear and most of the family decided to leave the north inner city.

The justice campaign: Who, why, what and who hasn’t

From the outset, the family had no confidence in the internal Garda inquiry which was initially led by Oliver Hanley, a senior Garda who had been stationed for much of his career at Store Street. Since then campaign members have done some research on Hanley and Larry is convinced that “He has been used as the clean up man…a ‘harm reduction’, ‘risk management’ man in the sense that he comes in and steam-rolls investigations through so the only possible conclusion is that the Garda do nothing wrong”.

Asked how the campaign got going, Larry replies, “I got in touch with all the politicians and started doing interviews. The family and friends organised a vigil on the 29th of September [after he died on the 16th]. It was huge. After Terence died, the cops were putting batons around young fellas and saying we will do what we did to Fuzzy [Terence’s nickname]”.

As some of the details of the case came to the community’s notice, the campaign, whose central demand is for a full independent public inquiry, soon gathered momentum. Since then the campaign has relied largely on friends, community members and the family to maintain its public profile although anarchists, Sinn Féin, the Labour party and independent left wing politicians have offered varying levels of support.

While Larry is careful to stress that “the campaign is open to people of all political persuasions”, he ruefully acknowledges “that on a political level very few people are willing to stick their neck out and call a spade a spade. A lot of politicians, not all of them though, in my experience, a lot [of] them…shouldn’t be sitting in Dáil Éireann[6] supposedly representing our community because they don’t.

I suppose I have learnt to be very sceptical of people, of politicians mainly”. He goes on to explain that even those who have pledged support “haven’t been useful in that they do not do the legwork. They turn up when the cameras are about” but stresses that the WSM, independent libertarians and some Labour party members have been more dependable.

Asked what this felt like Larry responds “It has been very hard in the sense that sometimes I felt very much on my own but…I never felt like giving up. Politicians would promise you the sun, the moon, and the stars and journalists and media were not showing any interest in the campaign whatsoever” at the outset.

As a consequence, Larry continues, “there has been a lot of stress on my family”. The Wheelock family are particularly scathing about the Taoiseach [7]. “Bertie Ahern lives in this constituency. He is an elected representative of this constituency. My brother died and lived in his constituency and Bertie Ahern has done nothing for the campaign. I protested outside his office because of the harassment my family received at the hands of the Gardaí.

All I got from him was that he rang me up and said he knew my family very well. He doesn’t know my family. My family aren’t Fianna Fáil. I have got no help from him and I do not expect any help from him. He promised he would get me an internal Garda report two years ago and I am still waiting on it. He ain’t interested in my brother and ain’t interested in what happened to my brother”. Interestingly, established community workers [8] in the locality were also slow to help out.

Larry believes this is because “they are all attached to projects funded by the Fianna Fáil government. Funding is a huge part of this. A lot of community activists are afraid to get involved. A lot of the jobs are funded and they are afraid of funding being withdrawn. They will how their face at protests but aren’t really willing to challenge politicians. They sit down with the Gardaí at the Community Policing Fora, [9] which were set up to improve relations with the community…but if the police are going around battering young fellas, storming homes, attacking women and children that isn’t better policing.

When I went to the local forum, they were not willing to take my case on. I was told that my complaint was outside their remit. I wasn’t asking them to punish the police. I was just asking to be a representative of my family – to mediate and allow my family to peacefully protest but they weren’t willing to do that”. According to Larry, the treatment of his family by the state stems from the fact that we live in a society divided by class and power.

Even before his brother’s death Larry thought “there was no justice – just us. I was always aware of the two tier society”. This has been reinforced over the past two years and he thinks one of the main lessons of his experience in organising his campaign for justice is that, “They all protect each other. No matter whether you are talking about hospitals, the police, or solicitors, they all look after each other.

That is what I have really learnt. The hospital and the forensic lab were covering up what the police had done – huge levels of collusion with each other”. He continues, “Ireland is a very small place [so] politicians and solicitors are all interlinked somewhere along the line”. It is clear from further remarks that he does not see this as a conspiracy but as a shared culture linked to networks of power, wealth and influence.

Asked what this analysis means in terms of the campaign demand for an independent inquiry, Larry argues that, “whoever the people are who are given the task responsible for investigating the circumstances of Terence’s death need to have carte blanche to question anyone…in the forensic department, the Garda or the hospital [and] who can question any independent witnesses and bring in their own engineers and pathologists.

The Ombudsman [10] is not a public inquiry because it can only deal with the Gardaí. An independent inquiry would question everybody…[to find out] first of all why was Terence arrested, find out why he had injuries… explain the detail. Somebody who has no ties with the Irish state at all. We know that the police can’t police themselves. Secondly, the Ombudsman has some ties to the judiciary and the police. The people we need cannot be compromised in any way. I want people named, shamed and charged.

Having said this, Larry then tails off and observes, “There will never really be justice for Terence. My brother died. You cannot equate someone going to jail with a life”. Despite these obstacles, the campaign “is bigger and stronger than before and…we are opening this up to any one to anyone who believes in it”. “Right now it is very hard to ignore. Just look at the last meeting [a large public meeting in the city centre that brought together other families and communities that have experienced police brutality].

There were loyal supporters but the majority of people were new faces. It is working and…it is having a desired effect. Discussing why the campaign has such a resonance, Larry notes that, “the campaign builds on its own merits [as] people know what extremes the police will go to. The feedback I get has always spurred on the campaign and has given a voice to the voiceless and hope to hopeless”. “The thing is police brutality is all over the country; it is prevalent and Terence’s story is not shocking to a large proportion of our population.

This is what brings people onto the streets. People have an empathy because they share similar experiences – maybe not to the same extreme – but at some stage during their life, they have been brutalised by the Gardaí. Now, I know how hard it is to get anybody for what happened to Terence but we are in a position that shows the ordinary man can make a difference and that what happened to my brother does merit an independent inquiry”.

Asked what practical impact the campaign has had Larry responds “I think we are winning already… we are winning in what has been put in place since Terence’s death. power to investigate allegations of police corruption and brutality.

There are now cameras in the station focused on the custody area. We know a lot of beatings that take place with the police happen in transit. I hope by the end of the campaign, we hope, there are cameras in vans and cars too… You can get your own GP [into the station] and the custody records are now catalogued and itemized so they cannot be ripped out [11] .

There is also this new law providing for a liaison Garda to check if there has been any mistreatment in custody. This is directly connected to the campaign. They may not be learning their lesson but it has put mechanisms in place that might be very useful down the line should [someone] be assaulted or die in custody”. There is also anecdotal evidence that the visibility of the campaign has reigned in some police excesses for the time being. “Before Terence there were a load of young fellas brought up to the Phoenix Park and fucked out of cars, brought up the mountains and young fellas were broken up but since Terence that hasn’t happened”.

Certainly in the north inner city the relative longevity of the campaign has meant that received wisdom about demanding justice from the state has shifted away from a defeatist and pessimistic attitude to the idea that the state and the police can be put under scrutiny. When this is put to Larry, he agrees, “What we have shown is huge. People are surprised that we are still here …Even after my family was harassed out of their home, even though I had charges thrown…at me and my brother…we are still going. It some way…has inspired a lot of people to – at the very, very least to complain”.

Larry and other supporters see a broad-based peaceful campaign as the key to any future success with the campaign. This means for Larry that, “Rather than setting the city alight like they have done in France, we have to find a way to make that people think this campaign is their campaign and that people are willing take upon themselves to give out literature. At every meeting, at every single meeting, [and] even on the street, people I have never met before…are only too willing to tell me their story. [The campaign] gives them a voice – it gives them a forum to talk about what is going on [in] their lives in regards to Garda brutality and harassment”.

Larry hopes that people use all the resources at their disposal to make sure the case stays in the public sphere asking people to “come out and show their support at demonstrations and public meetings, write to political magazines, newspapers, politicians, talk about it with their friends so it is always there”. And outside of Ireland, “set up support groups that are willing to distribute information [and] get in touch with human rights groups to show that something like this – as bad as it is – it has broke boundaries”.

We finish the interview with a discussion about Irish anarchism. I ask Larry how he saw anarchists before meeting them through the campaign and he replies, “I always thought that anarchists were people who wouldn’t pay their bus fare (laughs). No, more as late nineteenth century hooligans…ready to antagonise the state and who do no good”. This has changed because the “anarchists [are] willing to do the work, help with fund-raising, networking and leafleting…and have helped more than any other political group in the country.

Asked whether anarchist ideas are relevant he says, “There may be people who lean towards their ideology in working class areas” but “very few people where I come from would know what anarchism is or even what socialism is” and that the fact that most anarchists are often not from a similar background is a limitation in his opinion.

Finishing the interview, Larry says, “I have learnt that things like this are not solved overnight and there is a lot of legwork involved and [it] is a huge commitment that really infringes on your everyday life. But because of that, because of all we have put into this, it makes me more determined”.

Footnotes

[1] The police in Ireland are called An Garda Síochána which means in Irish the guardians of the peace.

[2]There have been numerous Republican, community and left wing campaigns that have drawn attention to the political nature of policing and patterns of harassment but community campaigns that look at ‘everyday’ policing have been less common with the notable exception of some of the activity of the Prisoners Rights Organisation which enjoyed strong support in the north inner city and a number of other working class communities in the early eighties.

[3] These are the two state exams in the secondary school cycle. The Junior Cert. is usually taken at age 15-16 and the Leaving Cert. at 17-18.

[4] A Safe Pass is a certificate that is required to work in the Irish construction industry

[5] The Coroner’s Court sits to establish the cause of death when it is not clearly of natural causes. After several sittings and amid controversy in early 2007 a split jury found that Terence died as a result of a suicide attempt. Much to the dissatisfaction of the Wheelock family and their supporters, the court refused to accept independent forensic evidence, explain anomalies in Garda accounts or admit an engineer’s report that found the Garda account of the ‘suicide’ implausible, if not impossible.

[6] Dáil Éireann is the lower house of directly elected politicians in the Irish parliament

[7] An Taoiseach is the Irish term for prime minister. The current prime minister is Bertie Ahern, the leader of the Fianna Fáil party and one of the representatives of the north inner city. Fianna Fáil is a populist, clientelist party and the sort of manoeuvre described by Larry, when a made-up family commitment to the party is claimed, is very typical

[8] Community based activism, ranging from Catholic ministry to radical grassroots projects, has been historically a very important part of Irish society. However, over the past two decades the community sector has become steadily ‘professionalised’ with volunteers being replaced by credentialised full time workers and the ‘sector’ becoming almost wholly reliant on state and EU funding.

[9] Probably one the most significant grassroots working class movement of the past two decades was the anti-drugs movement (see the following two WSM articles: http://struggle.ws/rbr/rbr6/crime.html and http://struggle.ws/wsm/ws/2005/89/drugs.html). Harassment of activists led to significant tension between this movement and the police. As a response to this and as an attempt to improve community relations in general, a number of pilot policing fora were set up – ostensibly to liaise and consult with community representatives.

[10] Historically, the Gardaí have only ever been investigated by themselves. Unsurprisingly, they rarely discovered problems with the way policing functions. The post of Garda Ombudsman, modeled partly on reforms in the north of Ireland to the PSNI, is a recent innovation and is looking at the Wheelock case ‘in the public’s interest’. As such, it is still an unknown quantity and it is too early to say what sort of approach the Ombudsman’s office will take but there are, as Larry notes, statutory limits to its power to investigate allegations of police corruption and brutality.

[11] The custody records in Terence’s case had been amended and altered including changing the names of the Gardaí involved in his arrest.

First published in Red and Black Revolution 14 March 2008