Over 30 years of anarchist writing from Ireland listed under hundreds of topics

James Connolly - from Anarchy #6

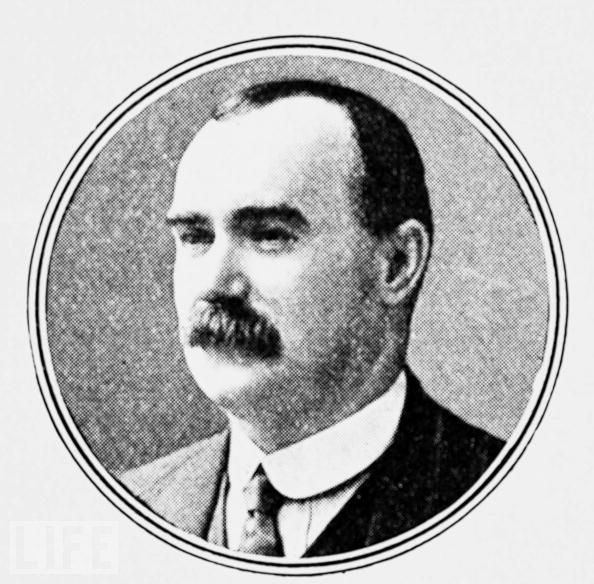

JAMES CONNOLLY (1868-1916) born in Edinburgh of a Co. Monaghan father, was Commandant-General of the Dublin Division. He was a member of the Military Council and Provisional Government. He founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party in Dublin in 1896. In 1903 he emigrated to the U.S.A., but returned after seven years. With Padraic Pearse he led the main Insurgent force from Liberty Hall to the G.P.O. Severely wounded during the fighting, he was taken after the surrender to Dublin Castle. Despite his condition he was executed - sitting on a chair - on May 12th, in Kilmainham Jail.

JAMES CONNOLLY (1868-1916) born in Edinburgh of a Co. Monaghan father, was Commandant-General of the Dublin Division. He was a member of the Military Council and Provisional Government. He founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party in Dublin in 1896. In 1903 he emigrated to the U.S.A., but returned after seven years. With Padraic Pearse he led the main Insurgent force from Liberty Hall to the G.P.O. Severely wounded during the fighting, he was taken after the surrender to Dublin Castle. Despite his condition he was executed - sitting on a chair - on May 12th, in Kilmainham Jail.

An Irishman’s opinion of James Connolly depends a great deal upon which political party he supports. Connolly has been hailed variously as a republican, a communist, a nationalist and a christian-socialist. All of the left-wing parties in Ireland have swooped like vultures upon his corpse and even the church, which he bitterly opposed during his lifetime, has shown some signs recently of joining in the chorus of lip-service paid to his name. All of this may be regarded as a measure of the high esteem in which Connolly is held by the Irish people but it serves to effectively obscure the political philosophy of James Connolly. He was executed as one of the leaders of the Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916 but he was not a republican. Before the rising he had told the members of his Citizen Army: “Being the lesser party we join in this fight with our comrades of the Irish Volunteers. But hold your arms. If we succeed, those who are our comrades today, we may be compelled to fight tomorrow.” What then persuaded Connolly to join in a fight with those whom he regarded as potential political enemies? In order to answer this question it is necessary to review briefly the evolution of his ideas, particularly those concerning the post-revolutionary form of society, which differ from those held by other political parties in Ireland and are thoroughly anarcho-syndicalist.

He was born on the 5th of June, 1870, in the small market town of Clones in County Monaghan of working-class parents. Very little is known of his early life but we may safely assume that he and the members of his family were not strangers to hardship and unemployment and that these factors prompted them to emigrate to Edinburgh, the Scottish capital, in an attempt to improve their lot. Young James at this time was under the legal age for work but nevertheless he got a job as a printer’s devil with the local “Evening News” until he was spotted by a factory inspector and the firm was forced to dismiss him. He next worked in a bakehouse and in a tile factory and then left for Glasgow where he settled for a spell before moving to Perth whereat the age of twenty-one he was married to Miss Lillie Reynolds. His father, meanwhile, had been disabled in Edinburgh and when the news reached Connolly he returned home and began work as a dustman with Edinburgh corporation.

During this period he became interested in politics and began to attend meetings of the Social Democratic Federation. The SDF eventually nominated him as their candidate for St. Giles Ward and since he had been obliged to give up his employment in order to secure the nomination his subsequent defeat at the polls forced him to take up other work and we next hear of him working as a shoe-maker but when Shane Leslie of the SDF suggested that he return to Dublin in order to help develop the socialist movement in Ireland, Connolly agreed. So in 1896 he returned to Dublin and yet another change of occupation. This time he worked as a navvy and a proof-reader, his previous experience with the “Evening News” probably proving helpful to him in the latter occupation. On August 13, 1898, the first issue of the paper with which his name was to become forever associated – “The Worker’s Republic” – appeared. It was published by the Socialist Republican Party and its publication was due mainly to the generosity of Keir Hardie who made a personal loan of £50. Since it was operated by voluntary labour it fell foul of the printers’ union and Connolly appeared before them on a charge of blacklegging. Connolly asked the union leaders if the use of private razors meant blacklegging on barbers? “The Worker’s Republic” continued in publication and he spent most of his time writing for it and on the first chapters of his book, “Labour in Irish History”, before setting out on a journey to New York that brought him in contact with a man who was to play an important part in shaping Connolly’s political thinking.

On arrival in America Connolly joined the Socialist Labour Party and was soon elected to the executive of the party which was headed by the famous American syndicalist Daniel de Leon. It may be appropriate to note at this point that on the issue of political activities there is a marked difference in viewpoint between syndicalist practice in Latin countries as compared with Anglo-Saxon countries. In the USA or Britain syndicalists may regard political parties as a necessary evil and may be prepared to use them as a means to an end but this is not the case with, for instance, the French syndicalist. The early French syndicalists rejected all forms of political activity regarding it as a waste of time and asserting that those who became involved in it would inevitably become part of the system. The trade union, they felt, ought to carry out the political education of its own members with the sole aim of overthrowing the state by means of the general strike. After the revolution parliament and representation by geographical areas would be abolished so why waste time in training politicians? The administration of the factories would be undertaken by the workers themselves and syndicates of teachers could run the educational system, syndicates of doctors the health service and so on. De Leon, however, believed in the organisation of a political party and Connolly gained much valuable experience with the SLP and learned a great deal about trade union administration as an organiser for the Industrial Workers of the World.

He returned to Ireland in 1910 and in 1911 he went to Belfast as secretary and district organiser of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union. Around this time he published his manifesto of the Socialist Party of Ireland which ought to make interesting reading to some Irish politicians who claim to be inspired by his ideas. Elections on a territorial basis would cease under a socialist form of society he said and “the administration of affairs will be in the hands of representatives of the various industries of the nation; the workers in the shops and factories will organise themselves into unions each union comprising all the workers at a given industry … the representatives elected from the various departments of industry will meet and form the industrial administration of a national government of the country … socialism will be administered by a committee of experts elected from the industries and professions of the land.”

During his time in Belfast the mill-owners decided on a speed-up within the mills and working conditions were made very harsh with a number of petty restrictions being introduced. The workers protested and the owners replied with the threat of a lock-out. ….

Transcription from the Anarchy No 6 publication(1970) .There are two pages missing from the PDF on the website, so it cuts off half way through.