Over 30 years of anarchist writing from Ireland listed under hundreds of topics

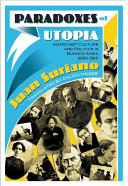

Paradoxes of Utopia - Anarchist culture and politics in Buenos Aires 1890-1910 - Review

‘We have taken a good path. As we see it, the formation of social study circles and the establishment of libertarian schools are solid, protective bulwarks in our race toward emancipation. They are the groundwork of the great revolution.’ - La Protesta Humana, January 7th, 1900

When the Argentine economy collapsed in 2001, many were surprised by the factory takeovers and neighbourhood assemblies that resulted. But workers' control and direct democracy have long histories in Argentina, where from the late nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, anarchism was the main revolutionary ideology of the labour movement and other social struggles. Most histories of anarchism in Argentina tend toward dry analyses of labour politics, lists of union acronyms, and the like. For Juan Suriano, that's just one part of the story. Paradoxes of Utopia gives us an engaging look at fin de siècle Buenos Aires that brings to life the vibrant culture behind one of the world's largest anarchist movements challenging the myth that anarchist was merely a euro-centric movement: the radical schools, newspapers, theatres, and social clubs that made revolution a way of life. Cultural history in the best sense, Paradoxes of Utopia explores how a revolutionary ideology was woven into the ordinary lives of tens of thousands of people, creating a complex tapestry of symbols, rituals, and daily practices that supported-and indeed created the possibility of-the Argentine labour movement. The author creates an innovative panorama that gives equal weight to the strengths and weakness of anarchism in Argentina, effective strategies and grave mistakes, internal debates and state repression, all contextualized within the country's broader political, economic, and cultural history.

The history of anarchism in Argentina also has a local angle as Irish born Dr John Creaghe also took part in the emerging movement returning to Argentina in 1894 to find anarchism under the banner of FAO and later FORA (Argentine Regional Workers' Federation) gaining enormous influence within the wider labour movement. Creaghe became editor of the daily newspaper ‘La Protesta’ which was closed down on numerous occasions. Alan O’Toole notes that, “It was the major paper of revolution in Argentina until recent years… its establishment and continuation was probably his greatest single contribution to the politics of revolution.” (See)

This immersing of anarchist ideas and practices into the emerging labour movement resulted in major state repression, including imprisonment, censorship and killings with the police estimating that there were around 5,000-6,000 anarchist militants in Buenos Aires alone during the first ten years of the century. Indeed the number of libertarian centres and anarchist circles peaked to 51 by 1904 dropping to 22 by 1910, overwhelmingly concentrated in working class neighbourhoods. For example in Rosario’s Casa del Pueblo, the centre was a collaborative effort between ten different groups. The list of activities carried out in 1900 speaks for itself: they found employment for 446 people, a library holding 380 books on science, art, sociology and literature; even a permanent orchestra and a theatre group, sixty four lectures and lent the hall to workers’ associations.

Conflicts occured constantly throughout the decade and the anarchists mobilised a large percentage of the city's workers-port workers, cat drivers, coachmen, sailors, mechanics, bricklayers etc. There were seven anarchist led general strikes including the renters strike of 1907 on other demands for union recognition and improvement in labour conditions. Libertarian centres, study circles, daily newspapers, to touching on all aspects of life; to more recreational activites such as literacy readings, music and libertarian dances provided the backbone this support. Thus the libertarian circle 'was an environment in which workers' cultures emerged-through the exchange of individual experiences, workers became collective and began to assume a shared identity.'(p19)

However, by 1910 the Argentine anarchist movement in terms of numbers and influence was in steady decline mainly due to brutal state repression, but the growth of social welfare in housing, education and work, voting rights and institutionalisation of labour disputes all contributing with the author pointing out that ‘there is no doubt that the tendency toward self-marginalisation, combined with their reluctance to analyse or even note domestic particularities, dramatically facilitated their separation from the workers’.

In a time whenever 'identity lifestylism' and 'escapism' dominates some sections of the libertarian movement, this book is a welcome critical reflection, providing lessons for our movement and a powerful account of how anarchists can built a strong social movement- a glimpse of what is possible with political coherancy and strategic focus. There are no short-cuts to social revolution and building a movement that is firmly entrenched and located within the wider working class.

http://www.wsm.ie/c/anarchism-south-america

This book is available from the WSM bookservice (Solidarity Books) or alternatively from Just Books Collective at the Na Croisbhealai workers co-operative in Belfast. Well recommended!