Over 30 years of anarchist writing from Ireland listed under hundreds of topics

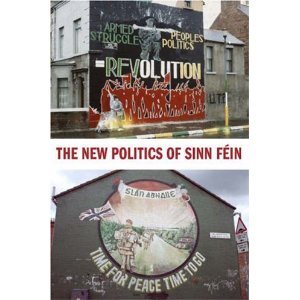

The New Politics of Sinn Fein by Kevin Bean- From Insurgency to Identity - Review

As someone who moved from Irish republican socialism to anarchism, Kevin Bean offers a convincing and fascinating insight into the journey and demise of radical republicanism in Ireland. It demolishes the ‘sell-out’ narrative promoted by some quarters of disaffected republicanism by diligently exploring the rapid transformation of the Provisional movement from a counter-insurgency to an active partner in governing the state it now eagerly upholds.

As someone who moved from Irish republican socialism to anarchism, Kevin Bean offers a convincing and fascinating insight into the journey and demise of radical republicanism in Ireland. It demolishes the ‘sell-out’ narrative promoted by some quarters of disaffected republicanism by diligently exploring the rapid transformation of the Provisional movement from a counter-insurgency to an active partner in governing the state it now eagerly upholds.

Bean locates Irish republicanism in a global political context and shows how its politics are comparable to other ideological projects that have undergone similar decline and redefinition since the late 1980s. The book considers the tension between the universal and the particular within republicanism and how this is reflected in specific aspects of republican politics with a complex dialectic between the British state and Republicanism.

The focus on the international context is particularly topical at the moment with the Arab Spring and global occupy movement. It is interesting how the numerous commemorations and articles invoking the uprisings in Paris, protests in London’s Grosvenor Square, fighting in Vietnam and radicalisation of the black civil rights movement in the USA have failed to mention Derry 1968 and the struggle for civil rights in Northern Ireland. Yet when Bean interviews IRA volunteers and republican activists, the extent to which they were inspired by other struggles becomes clear: ‘From its founding moment, the environment shaping the movement extended beyond the streets of West Belfast and the villages of East Tyrone to guerrilla campaigns in Latin America and civil rights activism in the USA’, writes Bean.

A couple of weeks ago, Kevin Bean gave a lecture in the Na Croisbhealai workers co-operative in Belfast summarising his book. Interestingly, using the releasing of British state documents he pointed out that the setting up of no-go zones in nationalist working class areas across the North (that were subsequently dismantled after Bloody Friday in 1972) were considered more of a threat to the authority and stability of the British state than the militarised and vanguardist campaign waged by the Provos. Indeed, this area of struggle and mass campaigns over internment and rent and rates strike remains largely unexplored.

While republicans drew inspiration from other radical movements, Bean shows that the movement never really had a clear definition of republican ideology. In very simple terms, in the late 1960s through to the mid-1980s the politics of the republican struggle were largely universalist and anti-imperialist in character, and influenced by ‘progressive’ struggles in Latin America, Africa, Asia and the Middle East. However, the author argues that Provisionalism is of deeply communal post -1968 version of republicanism and that the burning of Bombay street and outbreak of sectarian clashes formed the judgement of many republican activists more than the revoking of 1916 and past glories.

Since the late 1980s, in a post-Cold War world that has seen the further decline of the left, republican politics became prey to the particularist strand that always existed within the movement especially as it is located in one side of the sectarian divide. The republican leadership quietly revisited its universalist aspiration for a United Ireland with a united people, and moved towards embracing the politics of cultural difference and identity. As Kevin highlights, ‘While secularization and challenges to the political, social and sexual authority of the Church have certainly taken place since the 1960s, Catholicism remains an important cultural influence and an underpinning element of communal common sense, even for lapsed Catholics. Despite republicanism’s frequently bitter battles for hegemony with the Church, the parish and the community of the faithful were to leave a deep imprint on the community politics of the Provisionals.’ Indeed, this inability to build a revolutionary project transcending the sectarian divide remains a significant barrier today and can we witnessed during the recent Queen’s visit to the North in which particularist forms of opposition came to the fore. ( Read more)

Such brutal honesty was, however, nowhere to be seen in the republican movement’s leadership itself or its opponents in other factions. Instead, they presented the peace process as a successful outcome of their campaign, rather than analysing it as a logical conclusion to a long process of de-politicisation and accommodation.

With its rhetoric of ‘a new phase of struggle’, ‘new site of struggle’, ‘transition’, ‘opportunity’, ‘staging post’, ‘national reconciliation’ and ‘historical momentum’, the republican leadership, aided by the deliberate ambiguity of the peace process, was able to present a series of unprecedented departures from republican principles as great steps forward. There is no shame in defeat, of course; it can be an opportunity to take stock, learn lessons and search for a new form of politics that can address the continuing reality of British rule and political and social divisions. Yet there is something shameful about disguising defeat as ‘a new transitional direction’ or ‘building an Ireland of equals’

Unfortunately, the current leadership of the Republican movement has compounded its defeat by its political dishonesty, and its refusal to tell it like it is. With its constant advocacy of identity politics, pleas for truth and reconciliation and therapeutic rhetoric, republican leaders retrospectively undermine the essence of republicanism. For example, IRA volunteers who carried out attacks against ‘British crown forces’ such as Loughgall and Gibraltar were once considered as combatants in a war are now cast as victims that needs to be re-dressed through lobbying institutions of the British state.

A central theme running through Kevin Bean’s assessment is the role of the state displaying ‘soft power’ in terms of manufacturing consent in a Gramsci manner via the enormous ‘peace industry’ and funding of community groups in the ‘resistance community’. For Kevin this shaping of the social and political terrain by the British state that provisionalism operated from was a strategic success and had the greatest impact on the evolution of the movement to a fully-fledged constitutional movement as he explains ‘A growing focus on localism and communal (such as building resident groups against Orange Order marches) reflected a scaling down of ambitions as the Provisionals’ national project of transformation shifted towards a more limited representational role of petitioning within the political and social framework of the status-quo. Thus a process that had begun at this limited level would ultimately end in republican participation in government after 1998.’

For anarchists, the central thesis explored in this this book will resonate with the historical debate on the left over whether the state can be utilised as an instrument of working-class emancipation. Indeed, this transformation of Provisionalism, and Kevin Bean’s analysis to some extent supports the libertarian communist analysis of statism that far from 'withering away' it will only strengthen and recuperate any radical threat to the status-quo. Furthermore, authoritarian and hierarchal organisational praxis will be the gravedigger of any serious revolutionary movement because it removes power from the base. As Mikhail Bakunin predicted over a century ago, ‘This explains how and why men who were once the reddest democrats, the most vociferous radicals, once in power become the most moderate conservatives. Such turnabouts are usually, and mistakenly, regarded as a kind of treason. Their principle cause is the inevitable change of position and perspective.’(1)

While, this book is a must read, an excellent contribution offering a devastating critique of republicanism as a radical alternative to the status-quo in Ireland, it is equally important as revolutionaries and anarchists that we learn the lessons of past mistakes. Although Irish republicanism may have ideologically and intellectually exhausted itself due to its flexible contradictory nature, it remains a powerful attraction in Ireland which anarchists only ignore at their own peril as the anarchist movement and the wider left is yet to replicate the same influence in terms of building a significant social base and mass mobilisation within the wider working class.

1) p60. We, the Anarchists. A Study of the Iberian Anarchist Federation(FAI) 1927-1937