Over 30 years of anarchist writing from Ireland listed under hundreds of topics

Rojava: a new world in our hearts?

War is hell. In September 2015, the heartbreaking image of Alan Kurdi went viral. The picture of the little Syrian-Kurdish boy lying face down on Ali Hoca beach in Turkey highlighted Fortress Europe’s racist response to those refugees fleeing conflict in the Middle East. Abdullah Kurdi, Alan’s father, returned to Kobane to bury his wife and two sons. He wrote to the world: ‘I am grateful for your sympathy for my fate. This has given me the feeling that I am not alone. But an essential step in ending this tragedy and avoiding its recurrence is support for our self-organisation’. Kurdi was referring to the emergent experiment in popular democracy sweeping Rojava, the most hopeful thing to have happened in the Middle East for a very long time. A popular, anti-authoritarian rebellion is struggling against the death-world of capitalist modernity. And for now, it seems to be winning.

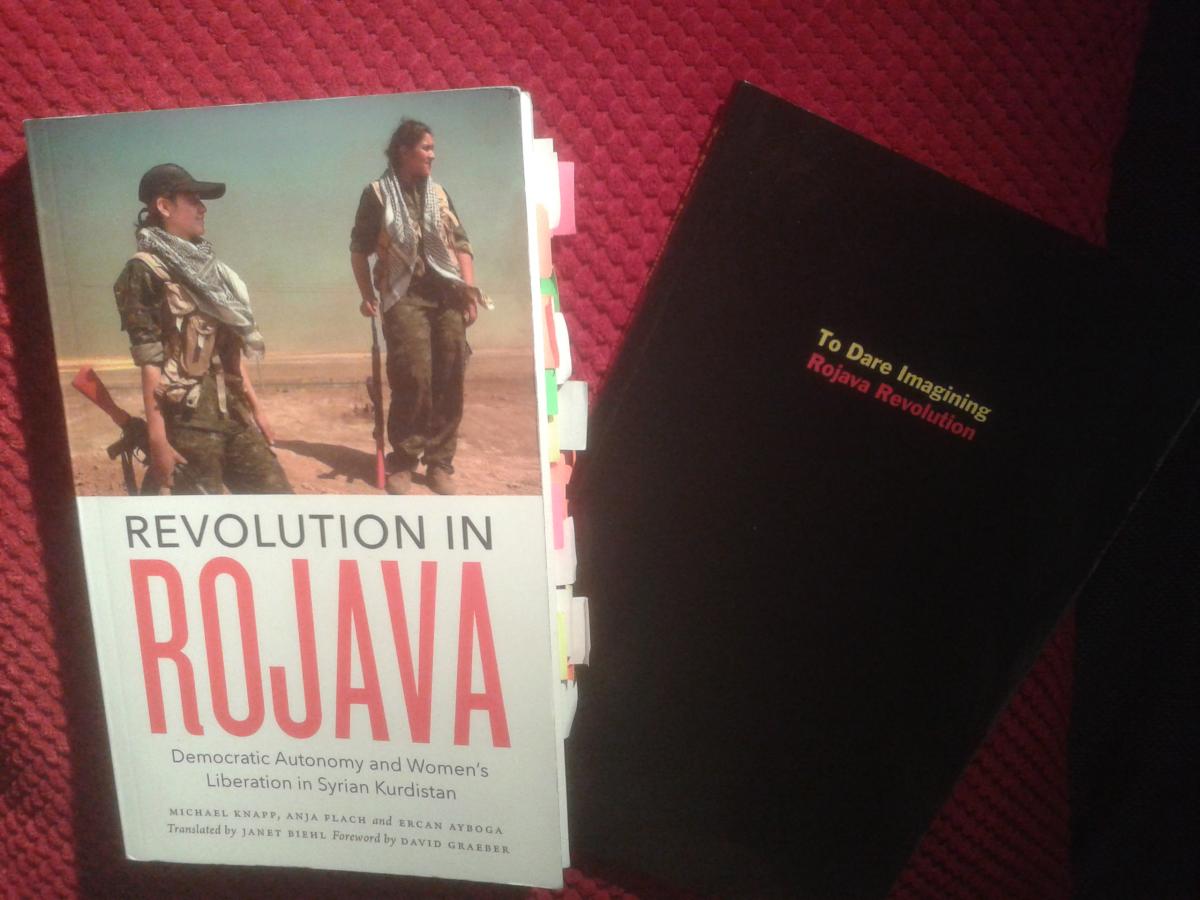

Two recently published books provide first-hand, well-researched and useful insights into the democratic experiment now unfolding in the three autonomous regions of Rojava. ‘Revolution in Rojava’ is a comprehensive account of everyday life in the region, reflecting detailed observations made in the course of the authors’ two visits to the region (Silemani, Til Kocer and Cizire in May 2014 and Kobane in early 2016). During these trips, they interviewed some 150 people and participated in many more informal conversations. These personal narratives are powerful, often moving and skillfully used to illustrate a changing, war-torn civil society and its newly emergent institutions and lifeways. In contrast to this carefully constructed picture of Rojava, ‘To Dare Imagining’ presents a wide-ranging collection of short texts, snapshots into the social and ideological transformation underway and its wide-ranging importance.

Before Rojava: organisation and learning

Although not in circumstances of their own choosing, men and women really do make history. As the conflict in Syria escalated in 2011, political authorities and economic elites deserted Kurdish areas in the north of the country. The PKK declared autonomy in the three cantons of Rojava: Cizre, Afrin, and Kobane. The following summer, the YPG and YPJ militias began to repel Assad’s forces, the Al Nusra Front (supported by Turkey) and ISIS (Islamist fascists). In January, 2015, their successful defence of Kobane from the deadly threat of ISIS brought the revolutionary struggle to the world’s attention. Within this popular alliance, however, the emergence of new movements for women’s liberation and for democratic autonomy was far from given. On the contrary, what becomes very clear from both books is not just that ‘Democratic Autonomy’ is a good idea, but that much organisational and educational work occurred in the two decades before the Syrian state’s fragmentation to ensure its success in practice.

During the 1990s, the collapse of the USSR had occasioned the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) to move on from Marxist-Leninist politics. Abdullah Ocalan, the PKK’s founder and imprisoned figurehead, advocated a thorough reorganisation of the Kurdish struggle. Against the former practice of patiently building a revolutionary vanguard party to seize state power and implement socialism from above, Ocalan counter-posed the idea of building participatory council democracy in the here and now. While the influence of anarchist Murray Bookchin’s ideas is perhaps well known, Ocalan also read widely into the stateless democracy writings of the Zapatistas, as well as the work of Michel Foucault and Immanuel Wallerstein. More interesting is the manner in which ideological change was purposefully translated into everyday conversations and activities. The PKK ran a Party Academy in Damascus which schooled more than ten thousand supporters in the new anti-vanguard ideology of revolution and stateless democracy. From 2003, within Rojava, the newly formed PYD (Party of Democratic Unity) further advocated Democratic Autonomy through people’s and women’s councils.

Core Ideas: Democratic Autonomy and Women’s Liberation

In outline form, Democratic Autonomy foregrounds the tight, intersecting linkages between patriarchy (the rule of men over women), capitalism (the rule of money), and the state (the rule of organised violence). It claims, rightly, that these forms of oppression cannot be overcome in isolation or in stages. Rather, a successful revolutionary movement must base itself in women’s liberation, and extend participatory, communal democracy into the terrain formerly occupied by the state and the capitalist economy. Without question, the most significant development concerns a new consciousness of women’s liberation. This is indicated by the formation of all-women militias, famous for their role in the defence of Kobane. Moreover, by the terms of Rojava’s Social Contract, every organised group must consist of at least 40% women. Both books underline the purposeful attempt to transform gender relations underway. Here too, education plays a crucial role. Since 2011, a network of women’s education and research centres has emerged. The stated goal of ‘jineology’ (literally, women’s science) is to reconnect science with society and to empower women by their reclaiming all forms of knowledge.

Rojava’s Anti-Authoritarian Insurrection

An incremental system of Democratic Autonomy emerged to fill the vacuum left by fleeing state authorities. Hundreds of delegates from local organisations across Kurdish regions established people’s councils. Revolution in Rojava details the emergent political structure. At the base is the Commune, which might consist of some 30-200 households on a street or block. By 2015, more than 1600 such communes operated in the Cizre canton alone. Each commune has a ‘people’s hall’ for resolving local social and economic issues and a ‘women’s hall’ for gender-based inequalities. In cities, a group of seven or so communes will send delegates to the neighbourhood assembly, which in turn will send delegates to the city-wide or district assembly. The ‘People’s Council of West Kurdistan’ (MGRK) includes all of the district assemblies. Significantly, at each level, a principle of pairing one woman/one man for every delegated position operates to institutionalise and promote gender equality.

Rojava then is an anti-authoritarian insurrection. A useful comparison is the Zapatista rebellion in Chiapas, Mexico. Similar to the Zapatistas, the Kurdish movement has sought to change a traditional society in the traditional way. Revolution in Rojava suggests that the flourishing council system took the region’s tribal traditions and infused them with council democracy, gender liberation, and respect for human rights. The book explicitly makes this comparison when discussing Rojava’s new and vital model of dispute-resolution. Peace committees, generally comprised of members elected by the commune, now operate to mediate and resolve interpersonal disputes and serious crimes. In all cases, the goal is not punishment of offenders but rehabilitation, not just of the individual but of wider social solidarity. Again, similar to the Zapatista commitment to the ‘Sixth Declaration’ outlining unifying aims, rights and responsibilities, the autonomous regions have evolved a ‘Social Contract’. This document, collectively agreed by more than fifty parties and organisations, emphasises the multicultural character of society, rejects the nation-state’s centralised model, and advocates gender equality, democracy and human rights.

The Future is Unwritten

Delegative democracy of the sort found in Chiapas and Rojava has past form. Previous revolutions, notably the American, European and Russian, saw ordinary men and women form councils and assemblies to decide the running of their workplaces and their communities together. Perhaps the most famous example is that of the Paris Commune of 1871, which saw a system of delegative democracy work to great effect. As Kristin Ross recently put it, the Communards did not stick to a blueprint but invented and re-invented, improvising a free society according to principles of association and cooperation. In all earlier cases, of course, these experiments in direct democracy were crushed either by the forces of counter-revolution (Paris Commune, German council movement post-WW1) or by the centralising vanguard party (Soviet Union post-1917). Will Rojava prove the exception to the rule?

Both books emphasise the improvised nature of these communities and their councils’ working existence. They highlight the very immediate existential threats (hostile neighbours such as Turkey and ISIS), and the more traditional challenges to popular, bottom-up structures (relations with pre-existing, centralised army and party structures). Moreover, notwithstanding the emergence of a social economy based around local co-operatives, the persistence of class relations remains a further issue. There are also long-term threats. Municipal administrations often lack financial and technical means to invest in infrastructure, vital to ensuring clean cities and safe drinking water, as well as to industrialising and making sustainable the cooperative economy. For all that, however, the fact that Rojava exists is already exceptional and a continuing source of hope that its principles can be realised.

Today, the authors of Revolution in Rojava conclude, it is imperative that all humanists pressure their governments to support Rojava and to withdraw their backing from IS and their allies. For leftists, solidarity with Rojava is not a question of benevolence but a necessity. This is not just about joining the hundreds of international volunteers who have fought in the militias, nor is it about responding to the very real emergencies that require humanitarian and medical aid. It is also about critically engaging with the ideas at the heart of the revolution – democratic autonomy, women’s liberation, environmentalism and a cooperative economy – as an alternative to the death-worlds of capitalist modernity. Understandably then, whenever activists in Rojava were asked what was the best form international solidarity could take, the most common answer was ‘Build a strong revolutionary movement in your own country’.

Books Reviewed:

Michael Knapp, Anja Flach and Ercan Ayboga (2016) Revolution in Rojava: Democratic Autonomy and Women’s Liberation in Syrian Kurdistan. London: Pluto Press. (Translated by Janet Biehl; Foreword by David Graeber; Afterword by Asya Abdullah).

Dilar Dirik, David Levi Strauss, Michael Taussig, Peter Lamborn Wilson (2016) To Dare Imagining: Rojava Revolution. New York: Autonomedia.

Ercan Ayboga, Janet Biehl and Aysa Gokkan were guest speakers of the WSM at the 2016 Dublin Anarchist Bookfair. For video recording, click here.