A detailed history with photos of pro-choice struggles in Ireland from the 1980's to 2007 and the involvement of Irish anarchist in those struggles. Includes the 1983 referendum (and those in 1986, 1992 & 1995) as well as the X-Case, the D-case and the Women on Waves ship. Written by a participant in almost all (if not all) of the events described.

A detailed history with photos of pro-choice struggles in Ireland from the 1980's to 2007 and the involvement of Irish anarchist in those struggles. Includes the 1983 referendum (and those in 1986, 1992 & 1995) as well as the X-Case, the D-case and the Women on Waves ship. Written by a participant in almost all (if not all) of the events described.

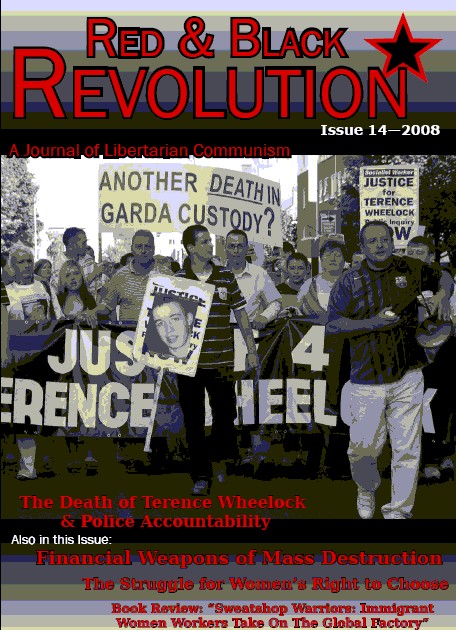

IMAGE: DAIC picket at Dail with the then illegal abortion information number

The WSM & the long struggle for abortion rights in Ireland

Last year saw a pregnant woman carrying a foetus which could not survive. The state insisted that she carry it to term. That is what Ireland’s anti-abortion law meant for Miss “D”, a 17 year old in the care of the Health Services Executive. She was four months pregnant when her foetus was diagnosed with anencephaly.

The outlook for individuals with this is extremely poor; stillbirth or death a few hours after birth. As the Choice Ireland group said at the time “No woman should have to endure the trauma of carrying to full term a child who will not live more than a few hours. By preventing “Miss D” from travelling to Britain for an abortion the Irish government are defining women as uterine incubators rather than individuals entitled to basic human rights”.

Abortion has been illegal in Ireland since the passing of the British 1861 Offences against the Person Act. And in Holy Catholic Ireland, it was not just illegal but also not spoken about. The only time it was mentioned in the newspapers was when Mamie Cadden was sentenced to death by hanging (eventually commuted to penal servitude for life) in 1956 for carrying out backstreet abortions.

When the British 1967 Act made abortion legal and relatively easy to access (if you could afford the cost of travel, accommodation and the procedure) it was not extended to Northern Ireland. Thousands of women from both sides of the border could, and did, travel to England each year to end crisis pregnancies. Nobody talked about it, the vast majority of women went alone and in secret.

At the beginning of the 1980s the Catholic church and its activist wing (the Responsible Society, Knights of Columbanus, etc.) became afraid that public opinion might change in the coming decades and the courts might say that abortion is permissible in particular circumstances, or even that the Dáil might eventually bring in limited legislation. There was no possibility of anything like that happening in the 1980s but they decided to plan ahead.

In 1981 the Pro-Life Amendment Campaign (PLAC) was formed with the goal of getting a Constitutional amendment, which would guarantee “the absolute right to life of every unborn child from conception”. Just over a month after it was formed, PLAC had been given promises by the leaders of Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and the Labour Party to hold a referendum. A referendum was called in 1983 and an amendment giving the “unborn” an equal right to life was proposed.

Having agreed to a referendum, Fine Gael and Labour subsequently had second thoughts and ran very muted and token Vote No campaigns. It was probably down to a mixture of fear of what might happen if they annoyed the bishops and a bit of ‘cute hoorism’ whereby both the Yes and No sides could be ‘supported’ in the hope of not losing their votes at future elections.

A small Women’s Right To Choose Campaign had been set up in 1980 by courageous women and men like Mary Gordon, Goretti Horgan and Pete Nash. This was tiny, but was taking the first steps towards opening up a debate about women’s rights rather than about whether the foetus had a soul. Along with liberals, feminists and the left they formed the Anti-Amendment Campaign.

Immediately, it was obvious that the AAC had a problem. While PLAC and their allies thundered against the “murder of babies”, the AAC were unwilling to argue their case on the basis of promoting women’s rights, and countering the lies about abortion. They were not unique in this, and it is difficult today to visualise the political atmosphere when the Catholic Church was an almost unquestioned authority on moral issues in Ireland, and opposing them was not done lightly. Much of the anti-amendment case was stated in terms of rejecting “sectarian laws” and supporting “pluralism”, rather than arguing for abortion rights.

In its leaflet asking people to vote no in the referendum The Workers’ Party achieved the seemingly impossible – not only did the leaflet not mention abortion, it did not mention women! One put out by the Irish Congress of Trade Unions opposing the amendment similarly avoided mentioning abortion, although women did make an appearance in the final sentence.

A woman’s right to abortion, even in very limited circumstances, was rarely mentioned by AAC spokespeople. Anarchists and other socialists were accused of “playing into the hands of PLAC” for advocating a woman’s right to choose, while liberal celebrities who started their speeches with, “I am totally against abortion, but also against the amendment,” were praised. If the abortion issue had been faced honestly and openly, the Catholic right would still have won, but the debate would have been more advanced.

Instead public discussion was dominated by lawyers and doctors whose case was that the proposed amendment was not really about abortion but about legal and medical issues ordinary people could not possibly understand. The PLAC message, on the other hand, was very simple: “abortion kills babies – vote yes”. On 8 September 1983 the eighth amendment to the Constitution of the Republic was approved in referendum by two thirds of the voters. Article 40.3.3 of the constitution now read: “The state acknowledges the right to life of the unborn and, with due regard to the equal right to life of the mother, guarantees in its laws to respect, and as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate that right.”

In Holy Catholic Ireland things went on pretty much as before. Just four months after the vote 15 year old Anne Lovett died giving birth alone by an outdoor grotto to the Virgin Mary in Granard, Co. Longford. Her baby died with her.

While looking for votes PLAC was anxious to assure voters that it was interested only in stopping the legalisation of abortion in Ireland. It had no intention to stop Irish women travelling to England for abortions. PLAC also said it would not oppose ending the stigma attached to single mothers. It was lying on all fronts and its hypocrisy was seen in the middle of 1984 when Eileen Flynn was sacked from her teaching job in a New Ross convent school for having a baby outside marriage. PLAC’s response was silence.

Defending her dismissal, a Jesuit priest wrote: “Ms Flynn’s pregnancy is significant only as being incontrovertible evidence that her relations with the man in whose house she resided were in fact immoral. Had her immorality remained genuinely private, it might have been overlooked”. In other words, had she gone to England and had a quiet abortion, she would not have been sacked. The wheels of reaction kept turning. 1986 saw us lose, by 2:1, a referendum to get rid of the ban on divorce. Defying the ‘advice’ of the Catholic bishops was not seen as an option by most voters.

There was also much scaremongering by antidivorce campaigners about women being left penniless. This was easy for them, as the government had not indicated what type of law they would introduce if the referendum was passed. It was to be 1995 before we finally, and very narrowly, won, and the ban was scrapped. Interestingly, the only people to the left of the Labour Party who were elected to the executive of the Divorce Action Group were two WSM members.

This reflected the respect that anarchists had gained through a strategy of uniting as many people as possible to remove the Constitutional ban, while reserving the right to put forward our own specifically anarchist positions (see ‘Divorce: Undermining the Family?’, WSM 1986).

The WSM produced a poster with a picture of the notorious paedophile priest, Fr Brendan Smyth, who had been protected by the church authorities for decades. The slogan said ‘The Bishops: they hid priests who raped children; now they lecture us about morals and children’s rights. Vote YES’.

Media analysts reckoned that this poster contributed to the victory by reminding people of the barefaced hypocrisy of the anti-divorce crowd. Once the ball started rolling there was no stopping it. Exposure followed exposure. Annie Murphy, who had had a love affair with the most populist bishop in Ireland, Eamon Casey, wrote a book revealing that he had a teenage son with her. Then we found out that Fr Michael Cleary, “the singing priest”, had had two sons by his “housekeeper”.

The massive and ongoing spate of scandals involving heartbreaking brutality in the Magdalen laundries, savage beatings of imprisoned children in Artane and Letterfrack, secret affairs by clerics who preached chastity and literally hundreds of child rapes by priests and Christian Brothers, were to destroy the moral authority of the Catholic Church.

A decade earlier it was a different story. Two years after the Eighth Amendment, in 1985, the Society for the Protection of the Unborn Child (SPUC) went to court to try to close down the two pregnancy counselling centres which provided information about how to get an abortion in Britain–Open Line Counselling and the Dublin Well Woman Centre. The Supreme Court ruled that providing such information was now unconstitutional.

Books, including “Our Bodies Ourselves” and Everywoman which contained information about abortion, were removed from Dublin libraries. Magazines like Cosmopolitan had to be printed with blank pages for Ireland when advertisements appeared for abortion services. One issue of the Guardian was seized from the Belfast-Dublin train and taken to Store St. Garda station because it contained an advert for a clinic which performed abortions.

Next SPUC went after the national students’ union, USI, and the students’ unions in UCD and Trinity College. Their members had voted, in college referenda, to defy a High Court injunction and continue to give details of abortion services, as well as adoption agencies and single parent groups, in their welfare guidebooks. Students were taken before the High Court but none were jailed for their ‘contempt of court’.

The fact that hundreds of students accompanied their representatives to each court appearance, blocking the street outside, was an indication that something was changing. Throughout the country the general mood seemed to be that censorship of information was not a good thing.

One might be against abortion but banning information on the grounds that women couldn’t be trusted with it was a bit too much. Perhaps the judges decided it wouldn’t be a good idea to turn brazen lawbreakers into martyrs? At this time some of the students saw a need to move beyond the colleges, and link up with other pro-choice supporters. Thus were born the Cork and Dublin Abortion Information Campaigns. These brought together students, feminists and left wing community and union activists.

The ban on information was defied, openly and publicly. They also made “choice” a central part of their platform by saying that the choice to have children must also be fought for. No woman should suffer poverty, problems at work, poor housing or any other disability because she chooses to continue a pregnancy.

Leaflets with the phone number of the injunction-busting Women’s Information Network were given out in their tens of thousands in city and town centres. Posters appeared on walls and hoardings, stickers in women’s toilets. Live TV reporters had to watch out or someone holding a poster with the WIN number could suddenly appear in the background. WSM members were very involved in all this. Our argument was that defiance of the ban was both possible and desirable, and would hopefully make that law unenforceable.

Workers Solidarity carried the WIN number in every issue, challenging the state to bring us to court. Maybe the fact that some of our members can eat two Weetabix at a single sitting scared them off, but they never accepted our challenge. The state did not look invincible, and that gave confidence to the new pro-choice movement that was emerging.

On February 6th 1992 news broke about a 14 year old girl, pregnant as a result of rape by a neighbour and reportedly suicidal. To protect her identity she was named as ‘X’ in the courts and the media. Her parents brought her to England for an abortion. While there they phoned the gardaí, asking about what DNA evidence the clinic should retain for a possible prosecution of the rapist. Instead they were told that they must return home immediately.

Attorney General Harry Whelehan had obtained an interim injunction on the basis of the Eighth Amendment restraining her from obtaining an abortion in Britain. The injunction was confirmed by the High Court 11 days later, when it ruled that the girl and her parents were prohibited from leaving Ireland “for a period of nine months from the date thereof”.

Up and down the country there was an explosion of anger. Thousands of mainly young women and men poured onto the streets to say “Let her go.” School students from several convent schools, particularly in Waterford and Cork, walked out in protest. Protesters took to the streets of Galway, Limerick, Waterford, Cork, Dublin, Tralee and smaller towns as well. Overseas the case received huge coverage, with more foreign news crews arriving every day.

Nobody had expected anything of this magnitude. At a lunchtime meeting before a Dublin demonstration the following Saturday the organisers were debating what to do if less than a few hundred turned up. An hour later at least 8,000 were in O’Connell St. Some reports said 10,000. That few expected anything like these numbers was evidenced by there only being five banners present (including the big red & black one of the WSM), but a sea of home-made posters.

This was not a moany tramp through the city centre; it was angry and energetic. People were shocked at the way ‘X’ was being effectively interned and forced to continue a pregnancy against her will. They also clearly felt enthused to be among so many others prepared to say abortion should be a choice available to every woman who needs it. I remember us bringing 1,000 WSM leaflets titled ‘it’s every woman’s right to choose’.

Within a five minutes they were all gone, people we had never seen before were giving it a quick read and then taking handfuls and passing them out. This writer was the rally chairperson, and remembers that for weeks afterwards he was being approached in the street by strangers, often older women, who wanted to thank the “young people” for finally breaking the silence.

For the first time a lot of people were seeing abortion in terms of a real living young woman, rather than emotive sloganising and theological debates. Thinking about what should be done if it was to be your own mother, or sister, or daughter, or aunt, or friend, changed a lot of people’s views. At the very least it left them willing to listen to a rational case for abortion rights.

Faced with growing anger the government took the unprecedented steps of offering to pay the costs of an appeal to the Supreme Court, enabling Ms X to travel to England. In doing so it interpreted the Constitution in a new way and changed Irish law in regard to abortion.

The Supreme Court judges who heard the appeal were not known to be harbouring any liberal or feminist thoughts. One of them, Hugh O’Flaherty, had represented SPUC in earlier cases against abortion information providers. It was an open secret that the government was putting pressure on the judges to make this case go away. They got their wish when the majority ruling turned the constitutional amendment on its head.

It decreed that abortion was lawful in Ireland in the event of there being “a real and substantial risk to the life, as distinct from the health, of the mother” as in the case of threatened suicide. The judges stood the law on its head and agreed that ‘X’ had a right to abortion. However in any other case, it would still be possible to obtain injunctions in order to prevent a women travelling. The “pro-life” movement was up in arms about abortion on hallowed Irish soil. The government did not want to face the embarrassment of further injunctions.

It was faced with two possible solutions to the thorny problem it faced: Either to resolve it through legislation, which would entail introducing abortion in some form into Ireland. Or to hold a referendum, thus avoiding the necessity of stating their own position on the issue. As politicians they did not want to alienate the pro-life movement, which is influential in rural areas. Neither did the party want to isolate the mass of new liberal working class voters that they were wooing as their traditional rural base dwindled. Their attempt to sit on the fence resulted in a referendum wording which neither side liked very much. The X case resulted in three proposed constitutional amendments, which we could all vote for or against in three separate referenda on November 25th 1992.

The Twelfth Amendment – the so-called substantive issue – proposed that the prohibition on abortions would apply even in cases where the mother was suicidal. The wording allowed for abortion in this country where “the life as opposed to the health” of the women was threatened “excluding the threat of suicide”.

The remaining two amendments were more straightforward: The Thirteenth Amendment would give a legal right to pregnant women to travel out of the country while the Fourteenth Amendment would allow (under conditions) the publication of information about abortion services in foreign countries. Soon after the “X” case DAIC adopted a Right to Choose position and made this the main focus of their arguments around the case.

People with divergent political ideas from the Workers Solidarity Movement, students, members of the Labour Party, the Irish Workers Group, the Greens, Red Action and other activists came together to distribute information, canvass, put leaflets in letterboxes, and organise meetings and marches. In the months that followed there were various different attempts to set up more broad based campaigns. DIAC continued its separate existence, co-operating with other groups on the ground where possible. Before the referendum, DAIC targeted different areas of the city for door-to-door leafleting and postering.

A Repeal the Eight Amendment Campaign (REAC) was formed in March 1992 on the basis of campaigning for a removal of the 1983 Amendment, for the provision of non-restrictive information and for the right to travel. It drew its membership from people who had been involved in the 1983 campaign and had been dormant since that defeat, from the existing abortion information campaigns and from members of the feminist movement with an orientation towards community politics (who also organised as the Women’s Coalition). It intended to be a broad based national campaign.

Meanwhile the more conservative elements of the feminist movement set about setting up a group, ‘Frontline’, based around the service organisations (Well Women Centres, Doctors For Information, etc.). They saw their role almost solely as a lobby group around the major political parties.

REAC was primarily based in Dublin, Cork, Waterford and Galway. From the beginning the campaign was split between the feminists who favoured lobbying and the left who emphasised campaigning on the ground. Of course it was said that the two approaches were not incompatible, but in practice REAC activity was centred on press conferences and letters to the Irish Times, at the expense of workplace and door-to-door leafleting and local organising.

One of the Women’s Coalition’s main spokespeople, Joan O’Connor, produced a discussion paper at a Dublin activists meeting on 1st September 1992, which said “To adopt a policy of abortion on de mand is not only politically incorrect if we wish to advance women’s rights in Ireland, but it is also a term which is extremely offensive to many women”.

This was coming from within the group which controlled REAC, which caused many activists to wonder what the point of the campaign was. Further tension was generated by the fact that most of the ‘leaders’ did not attend local meetings or engage in any of the ‘donkey work’ of leafleting and postering.

Public meetings and marches were not supported and not built for and, surprise surprise, not successful. A good example of this is that a REAC public meeting held in Dublin’s Liberty Hall, on the 20th October, just over a month from the vote was attended by just over 70 people.

As often happens, the divisiveness within the campaign was blamed on personal differences rather than politics. Eventually it became a waste of time and effort for activists to remain in REAC. The Dublin group collapsed, with most activists joining DAIC. The Galway REAC changed its name and went its own way.

In the months before the November 1992 referenda a broader Alliance for Choice was set up. The role of the Alliance was to make available posters and leaflets, and to co-ordinate press conferences. At last we had an umbrella structure to facilitate co-operation by pro-choice forces, but not a great one!

The Alliance however was hugely top heavy with a lot of affiliates who sent representatives to committee meetings but didn’t do much work. Most of the postering, leafleting and canvassing in Dublin was still done by DAIC and, to a lesser extent, the Women’s Coalition. This was only a few weeks before the vote. With the exception of Cork, Galway and Waterford few active groups existed around the country. The main problem affecting REAC, Frontline and the Alliance was their faith in the power of ‘leaders of opinion’ to win the battle for us

Letters were written to the Irish Times who came out in our favour Press conferences were repeatedly held, none getting more than a few minor mentions. The committee produced detailed briefing documents, holding meetings with organisations varying from the Council For the Status of Women to Fianna Fáil’s women’s committees. Yet in the end, the target audience, the progressives with power, refused to be pushed.

For the most part the voice of the pro-choice movement in Ireland was not heard by the Irish people. REAC acted as a flea on the back of the liberals but the liberals weren’t scratching. Increasingly, a lesson was being learnt that if abortion rights advocates don’t bring their case directly to the people, nobody else was going to step in and do it for them. The weakness of the pro-choice movement was matched by the confusion within the “pro-life” movement. Not only were they abandoned by Fianna Fáil but they were split on a number of fronts.

Firstly between those who wanted to campaign for a No vote in all three referenda and those who preferred the more acceptable face of allowing a Yes vote on Travel (their argument being that as you couldn’t actually stop women from travelling the amendment was impractical). The Catholic bishops collectively released a statement saying that Catholics could legitimately vote either way to the substantive question. Although a few bishops then broke ranks and called for a No vote, the “pro-life” movements’ mainstay argument that they represented the true wishes of Irish people had been undermined. Even on the question of abortion Information on which all elements agreed in opposing, the “pro-life” campaign didn’t even come close to matching the intensity and ferocity of the 1983 campaign.

With the setting up of a new “prolife grouping proclaiming itself as the organisation of the “pro-life” working class youth, a further split occurred. Youth Defence was publicly launched on Fr Michel Cleary’s 98FM radio show. They modeled themselves on the tactics of Operation Rescue type groups in the U.S. On marches they chanted “we don’t need no birth control, hey Taoiseach leave the kids alone”.

They leafleted on Saturdays in the city centres with gruesome pictures of supposed abortions. They picketed TDs’ houses, including those of Nuala Fennell and Eamonn Gilmore, and even Brendan Howlin’s elderly mother. They rang in death threats to Radio Dublin when they wouldn’t carry interviews with them. In one incident on Dublin’s Thomas Street pro-choice campaigners, were attacked with pick axe handles and snooker cues, resulting in broken bones. Youth Defence marches were “stewarded” by hired goons, complete with rapped knuckles. The music paper Hot Press ran an exposé on Youth Defence, following which the editor, Niall Stokes, had a concrete block thrown through the back window of his car.

The “pro-life” movement which had been careful building up an acceptable middle class image were horrified and attempted to disown the organisation. However mud sticks and Youth Defence became a graphic example of the threat of Catholic fundamentalism. This was later compounded in 2002 when its leader Justin Barrett was exposed as speaking alongside Hitler worshippers at neo-Nazi rallies in Germany. The ATGWU and SIPTU ran a joint campaign within their own unions calling for a “Yes, Yes, No” vote. The Irish Congress of Trade Unions released press statements opposing the government wording on abortion and produced over 150,000 leaflets arguing their case.

Unfortunately years of centralized bargaining had left the unions with little activist core to draw on, many of these leaflets never made it out of their wrapping paper. However it was indicative of the change that had occurred when two of the biggest working class organizations could take a strong position without any resistance from their own members.

A victory that dare not speak its name

In the end the electorate voted Yes to Travel, Yes to Information and No to the substantive issue. What did this mean? Considering that no “pro-life” group called for a “Yes, Yes, No” vote and “Yes, Yes, No” won, it’s likely that the majority of the vote on the substantive issue was for liberal reasons.

However it was impossible for many commentators to say this. On one hand political parties such as FF and FG contained both sides of the argument within their ranks. A politician would run the risk of alienating half of his party if he claimed victory for one side over another.

On the other side many liberal commentators were unable to identify themselves as prochoice. Instead of calling a spade a spade they stumbled over awkward phraseology. Rather than accepting this as a win for the pro-choice side it was for ‘those forces with a pro-women perspective’. It was a victory that dared not speak its name.

Previous to the referendum the Irish Times was warning “if the politicians who so vociferously criticized the FF wording do not revert to the issue…it will pass”. Yet the politicians did ignore the referendum and the wording did not pass. It is the view of many liberals that politics is for high profile players only, politicians, judges, journalists, professionals and bishops. The Irish people are only capable of looking on.

Home Rule is Rome Rule

In the previous 12 months the Irish people had changed politically. They voted for a woman’s right to information on abortion, they voted against a distinction between a woman’s life and a woman’s health. Yet just one year before the popularly held opinion among those fighting for abortion rights in Ireland was that we’d be lucky not to lose abortion information never mind a referendum on abortion itself. We were on the run.

So what caused the change? In general, the make up of Irish society had changed. Emigration had slowed down, with many young people returning to Ireland believing it better to be unemployed at home rather than in London or Manchester. An IMS poll for the Sunday Independent on February 23rd 1993 showed clear differences in attitudes to issues such as abortion and divorce along age lines. While 74% of those aged 18-34 thought the Eighth Amendment should be scrapped, the figures were 60% for those between 50-64 and 50% for those over 65. Many emigrants were returning from more secular countries and their attitudes on these issues reflected their experiences abroad.

With fewer US visas and rising unemployment in Britain in the early 1990s, emigration was no longer an easy option. Ireland was no longer exporting its most energetic and idealist youth. Young people who thought they could get out when they finished school or college found themselves staying at home in a country where there was still some truth to the unionist cry of “Home rule is Rome rule”. But they had a new sense of what they should be entitled to. They took to the streets in support of X, and to show they would not meekly accept the clerical domination suffered by their parents’ generation.

A second difference in Ireland was the movement of people from rural communities to urban areas. Within cities and larger towns, there are more opportunities to meet people with different experiences and a greater variety of ideas. People were not as bound by the ties of tradition.

The third and very important factor was the “X” case. This not only horrified many people but also for the first time identified a pregnant woman as more than just an incubator for a foetus. The reality of what it meant to deny women the right to abortion was made clear.

X put a human face to what had seemed an abstract issue. 2001 saw a dramatic initiative announced. The Dublin Abortion Rights Group (the new name of DAIC, which reflected the win on information and a new confidence about the possibility of winning the argument for abortion rights) and the Cork Women’s Right to Choose Group invited the “abortion ship” to visit Ireland. Moored outside the three mile limit, it would provide abortions for Irish women.

Women On Waves was a Dutch based group of doctors, nurses and women’s rights activists who had hired a ship and installed a medical facility. Dutch law would apply to the ship while it was in international waters. And the result of the travel referendum would make it hard for the state to prevent women going out to the ship.

This was a big story. Newspapers gave it the front page. Spokesperson, Dr. Rebecca Gomperts was on the Late Late Show. The whole country was talking about abortion. On the pro-choice side there were those who felt that this would be like waving a red rag at a bull and the likes of Youth Defence could seize the ship or beat us off the streets.

Others, the majority, saw it as moving from the defensive to a proactive outgoing type of campaigning. Only when the ship pulled into Dublin and tied up by the Ferryman pub on the south quays, did the Irish organisers learn that a permit required under Dutch law had not been secured. Without this, insurance for patients would be cancelled and there could be no question of providing any medical services.

It was a big let down, and everyone was angry at the Dutch for not telling us about the lack of a permit. It made the ship look like a publicity stunt rather than a real challenge to the government. Much more seriously, desperate women who had turned to the ship for help because they could not afford a journey to England had to be turned away.

Because of the public nature of the ship we had not expected many women to contact us seeking abortions but over 300 people contacted us. This astonishing number graphically illustrated how many women with crisis pregnancies have huge difficulty raising the money to travel abroad. Only tiny protests by Catholic fundamentalists and lone nutters materialised in Cork and Dublin. There were no bomb attacks, no marches, nothing of any note from the anti-choice side. They hadn’t gone away but they were a pale shadow of what they had been ten years earlier.

The pro-choice side, on the other hand, had put abortion rights back on the agenda, got 10 days of prochoice articles into the media, shown the particular issues affecting working class women and demonstrated that much of the violent fanaticism of the anti-choice extremists had withered.

Fifth referendum in less than twenty years

The anti-choice brigade was demanding yet another referendum to overturn the X-case ruling, lest any suicidal woman might seek an abortion. In 2002 the government gave them their fifth referendum in less than twenty years. The people who had worked together during the ship’s visit managed to bring together a wide range of liberal and left groups in an ‘Alliance for a NO Vote’ to oppose this.

Opposing us were Fianna Fáil and the Catholic Church, historically the two strongest forces in Irish society. With a general election due a couple of months after the referendum the other political parties kept a very low profile, not wanting to alienate any potential voters. Practically all the canvassing, leafleting and postering around the country was done by the Alliance.

With a budget of just £15,000 from fundraising, the ANV ran a very visible campaign, and one that did not shy away from the ‘substantive issue’ of abortion. The vote was extremely close, just over 10,500 votes separated the two sides, 50.42 per cent voted No, while 49.58 per cent voting Yes. A strong urban and rural divide was evident, with the urban areas strongly rejecting the proposals. Constituencies which rejected Fianna Fáil’s proposal included those of Bertie Ahern and then Health Minister Micheal Martin.

We had stopped them turning back the clock but, as a WSM statement for that year’s International Women’s Day celebrations said “Nothing will change for women who are not judged suicidal unless there is a real movement demanding the provision of abortion facilities for any woman who wants one in Irish hospitals. Irish Anarchists will continue to be at the forefront in building this movement”. 2007 saw the struggle joined by a new grouping which united a new group of younger people with those who had been active since the 1980s.

A meeting hosted by Labour Youth, and addressed by speakers from the Labour Party, Workers Solidarity Movement and the Revolutionary Anarcha-Feminist Group, saw a new pro-choice group come into being. Choice Ireland set itself the initial task of exposing the bogus pregnancy advice service calling itself the Women’s Research Centre, and also organized the daily solidarity protests outside the High Court during the Miss D case (as described in the introduction to this article).

The WRC, which operates from 50 Upper Dorset Street in Dublin, is run by Christian Solidarity Party members but advertises itself as if it provides abortion information. Instead, they try to stop vulnerable women considering abortion by telling lies such as “having an abortion would increase their risk of developing breast cancer, becoming an alcoholic and abusing children”.

Choice Ireland produced hundreds of stickers for use in the immediate area with warnings about the WRC’s real purpose. They have also drawn attention to the WRC’s lies with protests, leaflets and media coverage. It is unlikely that there is going to be a sudden political will to change Irish abortion laws. Commitments made by political parties to legislate along the lines of the X case usually evaporate as they get closer to general election time.

As Dr Mary Favier has written in this magazine (Red and Black Revolution) “any change to allow for suicide risk and foetal malformation would involve only a very small change in the law and would not substantively affect the lives of Irish women seeking abortion. The Labour Party has supported such a change in the law, if they were returned to government. They argue that this is all that can be achieved now and is thus better than nothing. It serves their private expressions of a pro-choice position while publicly sitting on the fence.

“Pro-choice activists need to be cautious about being drawn in to any broad alliance of support for such a limited legal change. Doctors for Choice would argue that this is a mistake as it continues to deny the reality of the 7,000 women traveling to England every year. At all times this issue should remain the focus of any campaign to change the law. Scarce energy and resources are better spent on creating an acceptance of abortion as a reality in Ireland. Any campaign should start with where it means to end – Irish women have a right to access abortion services in Ireland and the law needs to be changed accordingly”. [Read the full article]

Ireland still is a conservative country; the Catholic Church has been historically intertwined with the southern state. The majority of its citizens belong to the Catholic Church. Catholic ethos was enshrined in the constitution, in the laws, and in the education system. Catholic tentacles made their way into most areas of public policy. A sea change had occurred on the emotionally charged issue of abortion. As anarchists we are committed to changing the present system. This will only occur when the working class no longer accept the legitimacy of capitalism.

It is frequently argued, usually by those with a blinkered knowledge of the past that, it is impossible for society to change in such a fundamental way. Yet societies do change. People do break from the fixed ideas of the past. The human race is not inevitably stuck in a rut. What happened in Ireland in the 1990s is proof of that.

First published in Red and Black Revolution 14 March 2008